Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

Below are descriptions of two men. Imagine that both men have been rated in the top 10% for facial attractiveness:

- Man A is 35 and Mormon. He does not drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes, do drugs, or go to parties. He is active in the church. He began dating his current wife when he was 18 and got married at 24. He remains married and has two children. His total number of lifetime sexual partners is 1.

- Man B is 35 and nonreligious. He is a recreational drug user and loves to party. He met his first girlfriend at 18, but broke up after one year. Although he has had occasional short relationships, he has mostly spent time pursuing casual sex on dating apps. His total number of lifetime sexual partners is 32. He has two children, each from a different mother.

Despite being equal in physical attractiveness, there is a large discrepancy in lifetime partner count. One man has one lifetime sexual partner. The other has 32. The difference does not reflect a difference in physical attractiveness, but differences in behavior and personality.

It is common in general dating discourse for people to use the number of sexual partners as a proxy for physical attractiveness. However, attractiveness is not measured by how many people you have sex with. It is measured by how other people perceive your appearance.

Correlations of sexual partner count with physical attractiveness

A popular belief is that all men would be extremely promiscuous if they could. Also popular is the belief that the only thing holding individual men back from high levels of promiscuity is low physical attractiveness. This makes a few assumptions: a singular “male nature” where promiscuity is equally desirable to all men (no differences in traits such as sociosexuality). Also, an unwillingness to form monogamous pair bonds.

In other words, attractive men have a lot of casual sex. Unattractive men “settle” in monogamous relationships.

If this is true, we should expect a very strong linear relationship between male physical attractiveness and partner count. A single variable, attractiveness, should explain most of the variance in the lifetime number of sexual partners.

Let’s see what the research says about that.

Bogaert and Fisher (1995) found a Pearson’s correlation of r = .2 with male physical attractiveness and lifetime sexual partners. In psychology, the convention for interpreting correlation coefficients is that .1 is weak, .3 is moderate, and .5 is large. In other fields, these would all be considered small. Why? Well, human psychology is complex. It’s rare that any single trait, including physical attractiveness, predicts life outcomes very well.

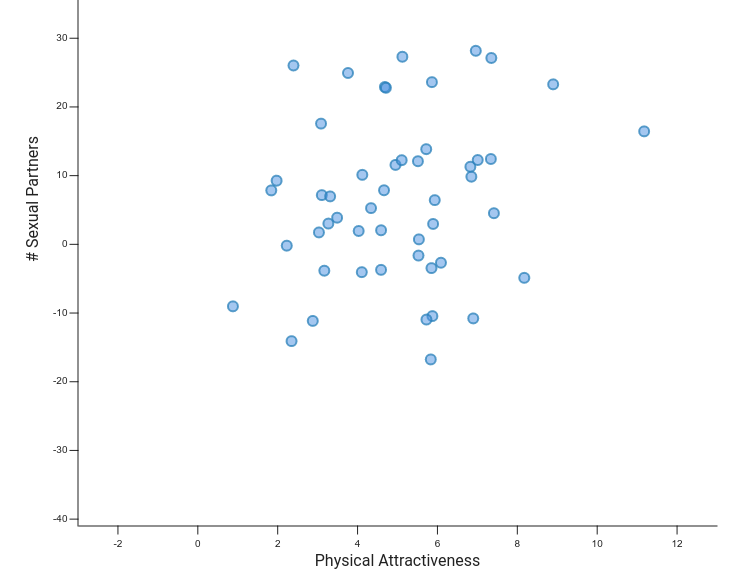

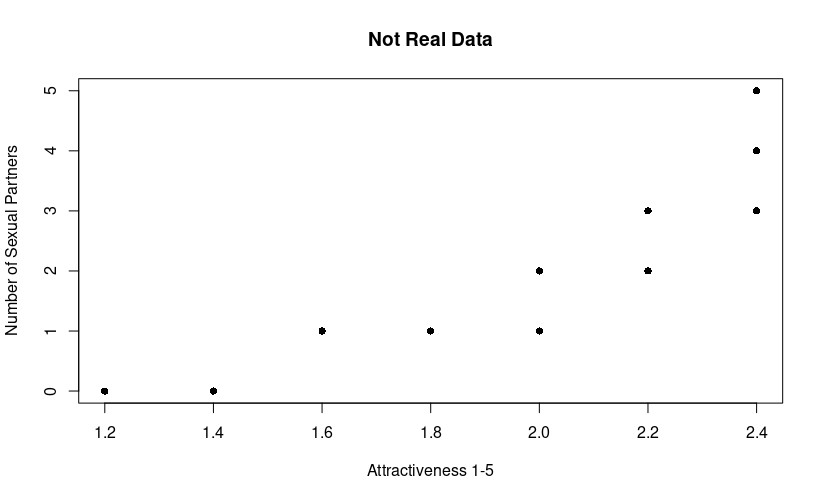

You can make up your own mind, however. This is what a correlation of .2 looks like:

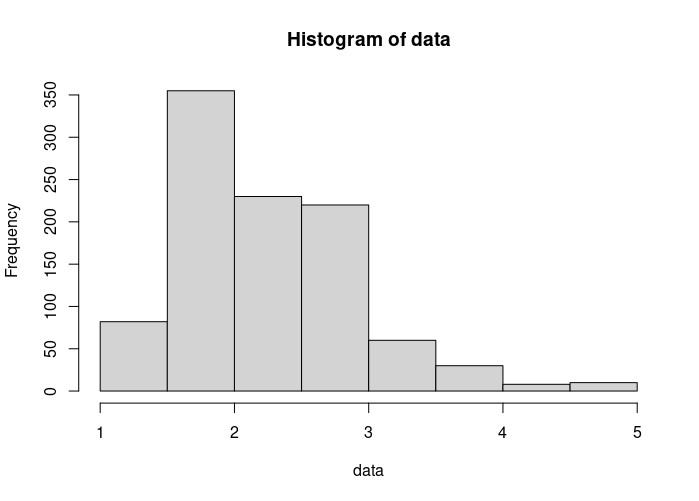

This is visualization data from R Psychologist, but I used the mean (6.6) and standard deviation (11.9) of lifetime sexual partners from Bogaert and Fisher (1995) with a mean male attractiveness of 5.

Keep what a correlation of .2 looks like in the back of your mind. Most of the results we will see are close to this.

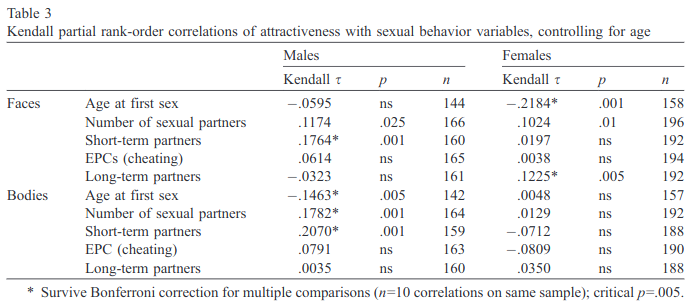

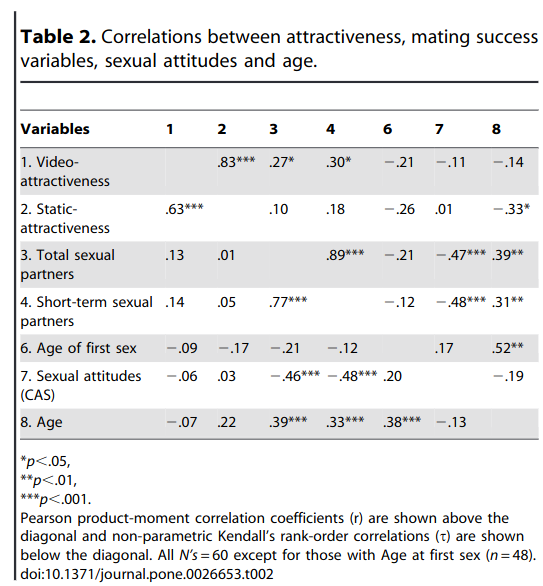

Rhodes et al. (2005) conducted a large study of facial and bodily attractiveness (including height in the body measurement). The effect size here is reported as Kendall’s Tau, rather than Pearson’s r, which has a convention cutoff of .21 for medium.

All of the attractiveness correlations were smaller than this, with only bodily attractiveness approaching a medium sized correlation with short term sexual partners for men.

Here is the table:

Weeden and Sabini (2007) examined the relationship between physical attractiveness, relationship status, and lifetime number of sexual partners. They did not find a statistically significant correlation between attractiveness and romantic relationship status (r = .11), while the correlation between number of sexual partners and attractiveness was significant, but small (r = .24).

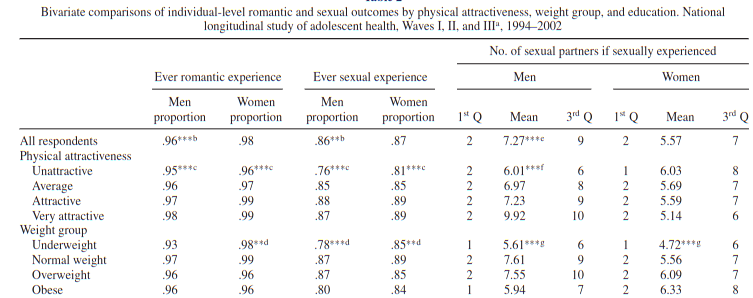

McClintock (2011) examined data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (ADD HEALTH) database, a very large (n = 14k) representative sample of young adults tracked over their lifetime. This included measures of physical attractiveness across life stages. In this paper, young adults were grouped into four categories: unattractive, average, attractive, and very attractive. Here are the results:

This shows the proportion of men by attractiveness category that has ever had sex and that has ever had a romantic relationship. Additionally, it shows the number of sexual partners and the interquartile range. Unattractive men were only about 10% less likely than the most attractive men to have had a sexual experience. There was no difference for romantic experience.

Further, the highest and lowest interquartile values were similar. The difference for unattractive men was statistically significant: they do have fewer sexual partners. However, there was no statistically significant difference between average, attractive, and very attractive men. Men who were overweight even had the same number of sexual partners as men in the very attractive category.

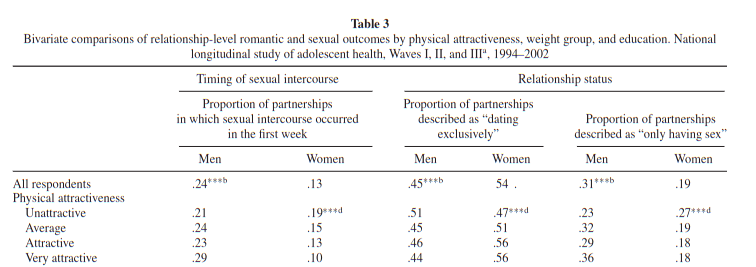

The chart above shows the proportion of men by attractiveness category who report dating exclusively and who report only having sex. None of the differences between attractiveness categories are statistically significant for men. In other words, attractive men are not more likely to be forming short-term casual relationships (at least in these results).

Another way to understand these results, from this paper: “for men, being very physically attractive (versus average/attractive) increases reported partners by 26%.” If the average man who is of average attractiveness has 7 partners, the average man in the very attractive category will have 8.82 sexual partners.

Leenaars et al. (2008) looked at a large sample of late teenage students across 52 high schools to assess the relationship between attractiveness and sexual behavior. The relationship was significant, but again small: .11 for past sexual behavior and .17 for recent sexual behavior.

Peters et al. (2008) found a small correlation between mating success and physical attractiveness (reported as Kendall’s tau, .14, .11 when controlling for age).

Rhodes et al. (2011) tested correlations between facial attractiveness in photos and on video of participants with sexual behavior. The faces in photos and videos were male, while all raters were female. Attractiveness in photos was not significantly related to number of sexual partners (.10), while video attractiveness was (.27). Short-term mating success was measured by the number of partners in the past month. Physical attractiveness in photos was not significantly related to short-term mating success (.18), but in videos was (.38).

In a large, nationally representative sample, Seffrin & Ingulli (2021) found a low but significant correlation between physical attractiveness rated by observers and sexual partner count (.07).

A meta-analysis of attractiveness and partner count

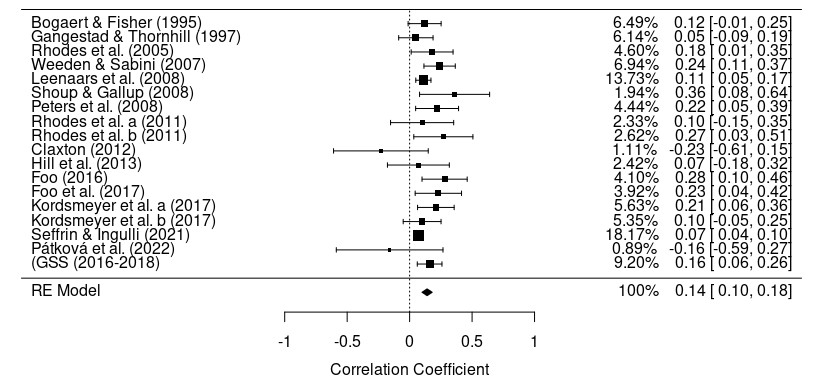

I could just go down the list and report the results of every paper, but there is a better way to do it. I dug through the literature and found all of the papers that I could that examined a relationship between sexual partner count and physical attractiveness. The data includes only men. I am sure there are some I missed, so if you find one then leave a comment and I will update the chart. I also ran the correlation from the GSS dataset’s RLOOKS variable for the years 2016 and 2017 and number of sexual partners. Here is the result:

We see a relationship that is very consistent, but very small. In other words, male physical attractiveness is not closely related with sexual partner count. The meta-analysis produced a result that was smaller than our starting point in Bogaert and Fisher (1995). This is a Hedges’ g of .14.

Is there evidence of publication bias?

Since publishing this article, a few people have asked if there may be publication bias. Publication bias primarily concerns the tendency for papers with statistically significant results to get published and papers without significant results to be withheld. Academic journals are biased toward the publication of statistically significant results (they are more interesting) and may not publish null results (they are more boring).

What does this mean in a practical sense? If you only publish significant results or large estimates of effects, then the true effect may be smaller or nonexistent. Given that most of the results in this meta-analysis were significant, we probably wouldn’t expect publication bias to result in a larger estimate. In other words, if you thought that publication bias meant the real relationship between attractiveness and lifetime sexual partners was larger, you would be looking in the wrong direction.

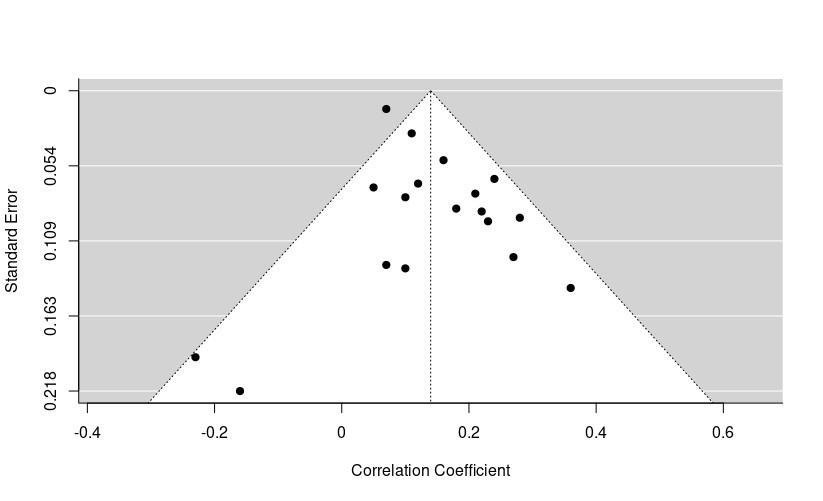

A funnel plot is a graphical representation used in meta-analyses to investigate publication bias, a type of bias that occurs when studies with negative or null results are less likely to be published, leading to an overestimation of the true effect size. The plot displays the sample size or precision of individual studies on the x-axis and the effect size on the y-axis, and shows a funnel shape where smaller studies with larger standard errors are scattered more widely at the bottom, while larger studies with smaller standard errors cluster more tightly at the top. Any asymmetry in the funnel plot may suggest publication bias or other sources of heterogeneity, and can be further examined by statistical tests or sensitivity analyses.

A funnel plot can’t actually show that publication bias is really the cause of asymmetry (data may actually be asymmetrical due to heterogeneity between studies or differences in methodology; it may also be chance). However, it’s one way that we can rule out publication bias.

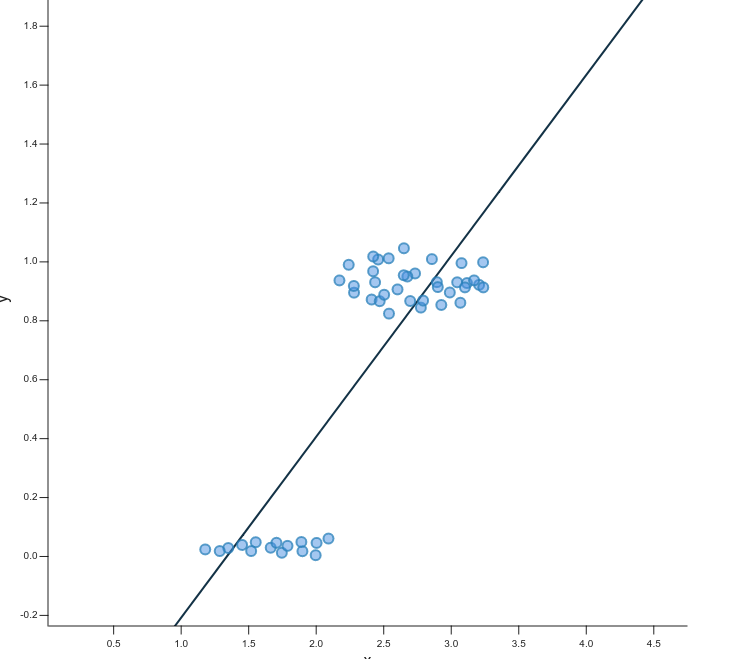

Here is a funnel plot of the data:

We can also use the Egger test to see if our funnel plot is really asymmetrical. The Egger test is a statistical test used to assess the presence of publication bias in meta-analyses. The test evaluates whether the intercept in a regression model of effect estimates against their precision (i.e., the standard error or inverse variance) deviates significantly from zero, which would indicate funnel plot asymmetry that is unlikely to occur by chance alone.

Egger test results gave a z value of 1.2115, indicating a non-significant result (p = 0.2257). The limit estimate as standard error approached zero was 0.1002, with a confidence interval ranging from 0.0376 to 0.1628. This result suggests that there is no evidence of significant funnel plot asymmetry in the meta-analysis. The limit estimate indicates that the average effect size may be slightly overestimated for small studies with high standard errors, but this bias is not large enough to affect the overall conclusions of the meta-analysis.

Partners in the GSS

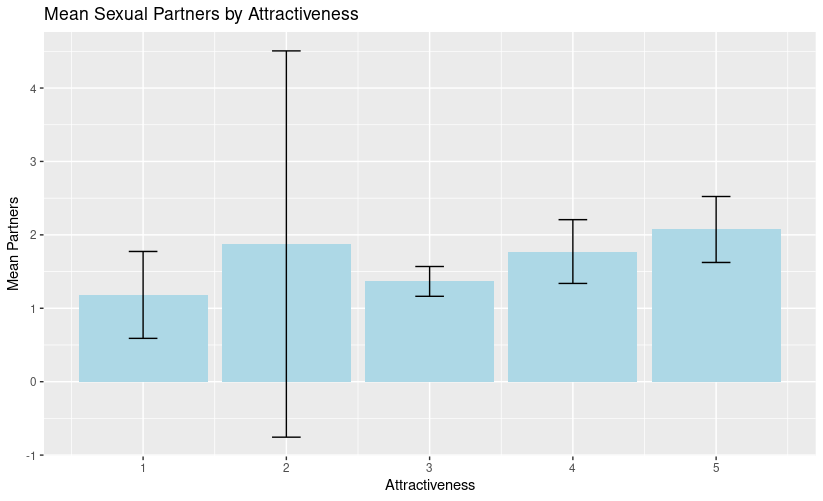

Here are the mean number of partners by sexual attractiveness in the GSS. 1 is the lowest (very unattractive) and 5 is the highest (very attractive):

You can already tell by looking at the error bars, but running an ANOVA on this reveals there is no statistically significant difference between groups (F(4, 370) = 1.76, p = .136). This is consistent with the McClintock (2011) ADDHEALTH study; individuals in the more attractive categories did not have more sexual partners on average.

In this section, we enter a hypothetical world where attractiveness and sexual activity are highly correlated…

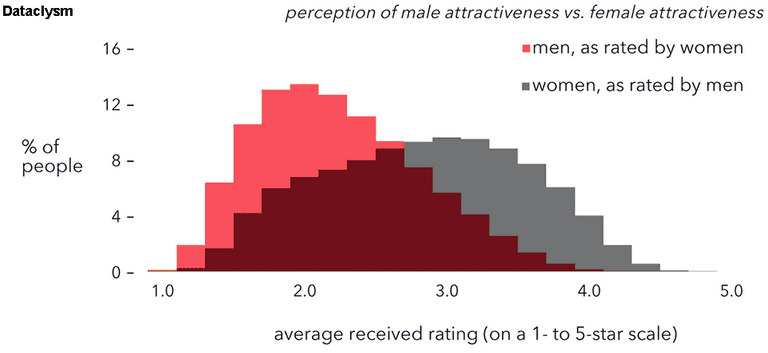

What would it look like if there were a perfect linear correlation between physical attractiveness and sexual partner count for men? We can run some scenarios based on the distribution of male attractiveness from the OKCupid dataset.

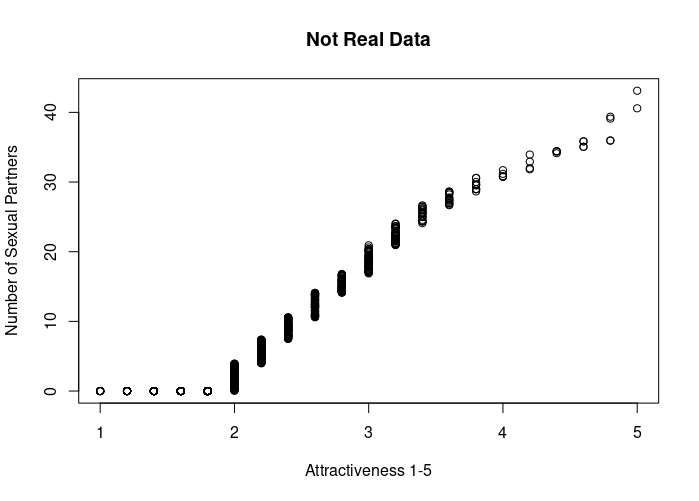

I created a random dataset of N = 995 following the OKCupid distribution of female ratings of men. The number of sexual partners is based on the mean and standard deviation in Bogaert and Fisher (1995). Then I sorted both from lowest to highest, in order to create a correlation with an r of .96.

I made sure that 30% of my dataset had a lifetime sexual partner count of zero. This is much higher than representative estimates for lifetime virginity (which range from 1-6%; see Are 27% Of Young Men Really Virgins?). However, I wanted this to represent a worst case scenario. What if attractiveness were the only thing that predicted sexual partner count, what if 30% of men were permanently sexless, and what if the relationship between sexual partner count and attractiveness was perfectly linear?

Clearly this looks very different from the real effect size of .2 we saw in the first chart. However, men who are below average attractiveness would still be having sex if the relationship were perfect. The cutoff is around 2. This scale is five points, so on a ten point scale this would be a man who is rated a 4 out of 10. The average number of lifetime partners for a man who is a 5 out of 10 would be a little bit less than 10. This is very close to representative data on the average lifetime number of sexual partners for Americans as well.

In other words, even if attractiveness were an extremely good predictor of having lots of sex, and even if 30% of the population was never able to have sex because they were too ugly, the average man would still be having sex.

I raise this point, because there is a narrative that says the average man cannot have sex in the modern dating environment. While it’s likely the case that low physical attractiveness bars the least attractive men from romantic relationships, it’s certainly not the case that the truly average man is excluded entirely.

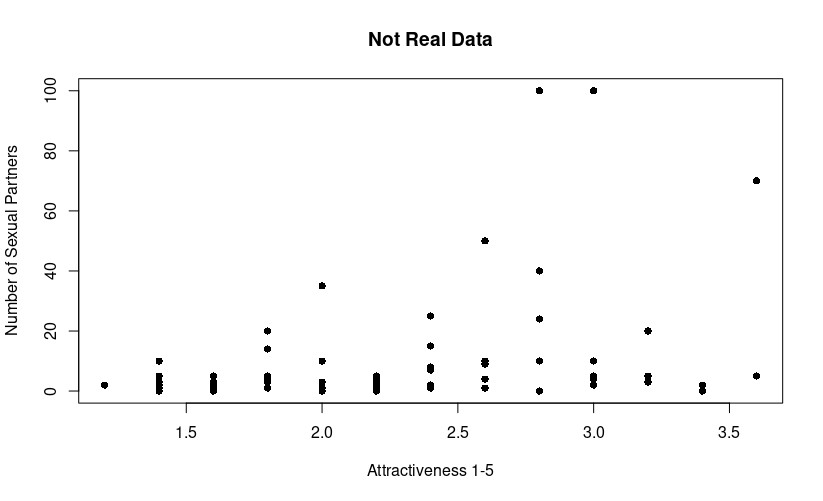

What if the relationship were curvilinear? Let’s again use the distribution of attractiveness from the OKCupid dataset for our model. We will also look at the lifetime number of sexual partners based on the General Social Survey (GSS).

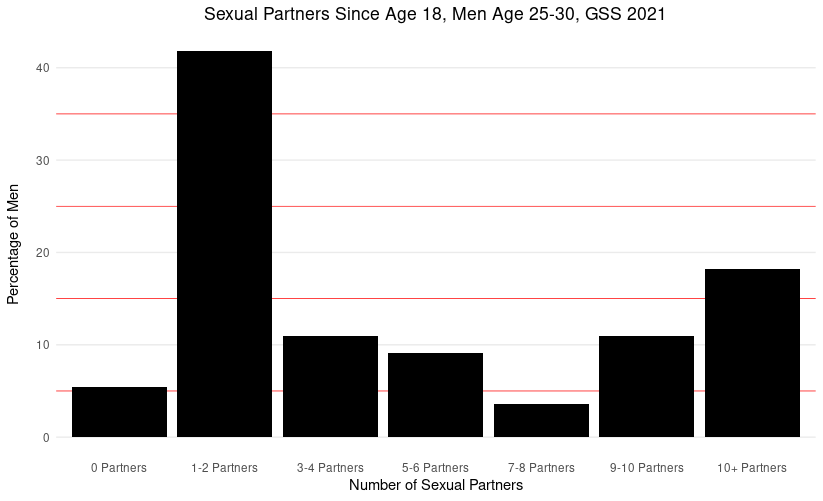

Here is the actual GSS data on the number of female sexual partners since age 18, for heterosexual men between age 20-30:

8.64% of men have had no sexual partners within this age range. In the OKCupid dataset, 8% of men were rated a 1.4 out of 5 or below. What happens if I sort the number of sexual partners in the GSS from lowest to highest and correlate it with the same number of men sorted according to the proportions in the OKCupid dataset?

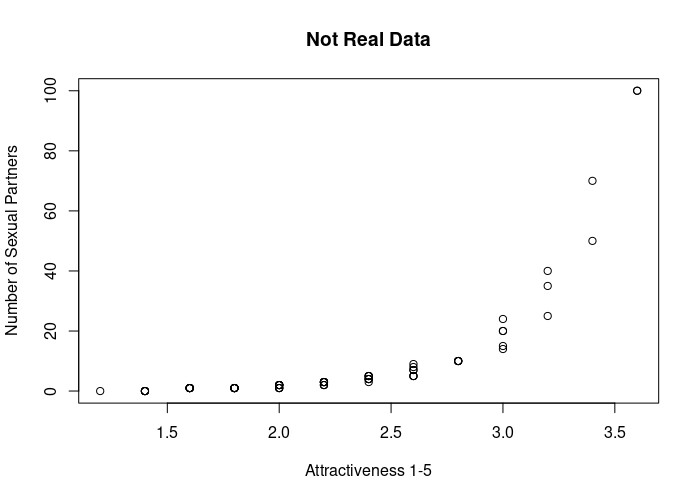

We have a wide range of values on the Y axis, so let’s zoom in and see what is going on with the men who we expect to be rated below average in attractiveness:

Assuming that attractiveness had a tight correlation (this is .9), the point where you would break out of the incel zone is a 3.2 out of 10.

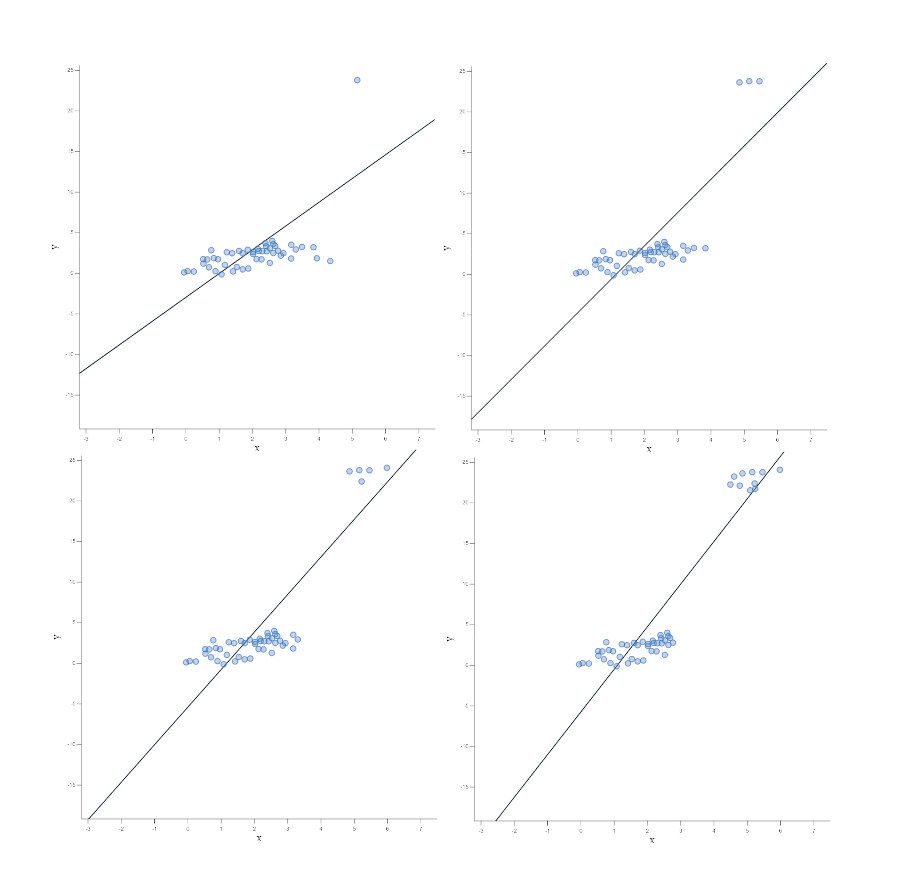

But as we have seen, the correlation between physical attractiveness and number of sexual partners is not very big. It’s around .2, so here is what happens if I reorder the Y variable until I get a correlation kind of close to that. Here is a larger one, at .35:

The data does not have to look exactly like this. It is randomized within the parameters taken from the OKCupid dataset and the GSS. In other words, we must see a number of values that reflect the attractiveness ratings women gave to men in the OKCupid dataset, we must see a number of values that reflect sexual partners in the GSS, and they must have a positive correlation of .35, where sexual partners increase on average as attractiveness increases.

We can test the Chad theory, too. What happens if most people are having very little sex except for the very top tier of men? This is what happens if most people are clustered at low sexual partners, while the top 2%, 5% 10%, or 20% of men are having all of the sex:

This gives you large correlations due to leverage points, about .8 to .9 in these. Okay — but maybe researchers remove the leverage points. Here is what happens if we remove the ghost Chads and look at a sample where 30% of men are sexless and the remaining men are having very little sex:

This is a correlation of .84. If “mid” men are having very little sex and unattractive men are having none, you should still see a large correlation between attractiveness and sexual partners. Even if you remove the Chadoutliers. You can fiddle with the data in various ways, but you’ll have a hard time putting the dots in an order where the least attractive men have no sex, mid men have slightly more, the most attractive men a lot of sex, and still see a low correlation.

That is the point of the correlation being low: we don’t see much of a relationship between physical attractiveness and total sex partners. You get low correlations when individual data points can fall pretty much anywhere. In this specific context, it means that men low and average in attractiveness may have a lot of partners, while men high in physical attractiveness may also have few.

This, however, does not mean that attractiveness is not a necessary criteria to have a lot of sex. It can also mean that attractive men simply don’t pursue casual sex as aggressively as our common folk psychology tells us.

Additionally, it may mean that being mid is sufficient. The “looks test” is binary. You pass it, you’re in, and from that point you can choose to pursue casual sex or you can choose to have a relationship. You meet the threshold and you’re not handicapped in dating, at least not that much.

This would be consistent with what is seen in a large part of the PUA (Pick-Up Artist) subculture. Set aside the anonymous grifters selling seduction fantasies. The PUA subculture does have men who “show their receipts,” or share proof that they do have success with women. These are often men who are quite average, but who do their best; they spend a lot of time trying to pick up women, they optimize, and subsequently they have frequent casual sex as a result.

What makes the real PUAs really stand out in my opinion? Well, they want to live that lifestyle and they try. A highly attractive man will have an easier time of it. However, at the same time, many attractive men (and men in general) just want to have a girlfriend. Attractive men who are successful with women also get into relationships, fall in love, and form pair bonds.

Yes bro, it is unironically personality (and other physical traits)

If physical attractiveness isn’t a strong determinant of having a lot of sexual partners, then what is? Pretty much all personality traits predict sexual partner count as well as physical attractiveness does. At least the relevant traits you would expect to. Additionally, so do other physical traits that are not facial attractiveness.

Hughes et al. (2004) analyzed opposite-sex ratings of vocal attractiveness. In other words, how sexy do women find your voice? The correlation between vocal attractiveness and number of lifetime sexual partners was .35 and .4 for the number of extra-pair copulations (infidelity, or casual sex).

Weeden and Sabini (2007) found that alcohol use, drug use, and liberal sexual morality all predicted the lifetime number of sexual partners with correlations between .3 and .5. Alcohol classically makes people more likely to rate others as more attractive and more likely to engage in casual sex (Jones et al., 2003).

As described in the first section, Rhodes et al. (2011) found significant relationships between physical attractiveness on video and sexual partner count, but not physical attractiveness as rated in photos. Why might this be? Well, one explanation could be that personality is more easily expressed on a video. The correlation between facial attractiveness ratings in photos and videos was very high (.83), so it probably isn’t the case that photos are worse at conveying what a person looks like.

What we do know from past research, very consistently, is that behavior and context shape perceptions of physical attractiveness. Facial expressions, movements, emotions, immediate surroundings, and the clothes you wear may all cause participants to give higher ratings of facial attractiveness. Townsend & Levy (1990) found that the same male faces were rated as more physically attractive when paired with a vignette describing them as high or low status. Similarly, in a second study Townsend & Levy (1990) found that men were rated as more physically attractive when dressed in nicer clothing. Men are rated as more physically attractive by women who know them personally and as less attractive when described as lazy (Kniffin & Wilson, 2004). Amos and McCabe (2017) even found that feeling attractive predicted having more sexual partners.

Raffaelli & Crocket (2003) found multiple demographic factors that predicted having more sexual partners: being from a single-parent family (.15), having a mother that had birth at a younger age (.15), and peer pressure (.16).

Walsh (1993) used the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI) to assess trait masculinity. Physical appearance was, as should be expected at this point, weakly correlated with the number of sexual partners (.11), while masculinity was a slightly better predictor (.15). Instrumentality in the BSRI also predicts sexual partner count for men (.28).

Bogaert & Sadava (2002) found that a secure attachment style was associated with fewer lifetime sexual partners, while an anxious attachment style was associated with more partners.

Seffrin & Ingulli (2021 found associations with a number of behavioral variables and lifetime sexual partners in a large representative sample. I reported this in the first section as .07 for physical attractiveness and partner count. Here are the effect sizes for the other significant predictors: violence (.07), drug use (.15), alcohol use (.12), picture vocabulary test (.06), “A” student (-.3), height (.03), and self-control (-.06).

In Rhodes et al. (2005), bodily attractiveness was a better predictor of sexual partner count than facial attractiveness. That bodily attractiveness is a bit better of a predictor of sexual behavior is fairly consistent in the literature. Hughes and Gallup (2002) found that male shoulder-to-height ratio — basically the desired male v-taper — predicted sex partner count at r = .26 and extra-pair partners at r = .34. In the large representative study by McClintock (2011), it was found that overweight men had as many sexual partners as very attractive men. This was measured by BMI, so it’s possible that many of these men were not actually fat. Many of us who lift are still within the overweight BMI category even when shredded. We may be seeing an effect of muscularity.

In Rhodes et al. (2005), sexual attitudes were a better predictor of total sexual partners and short-term mating (partners in the past month) than physical attractiveness assessed by photos or video. The largest association with physical attractiveness was in the video condition (.30) with short term sexual partners. Attitudes toward casual sex were much better predictors, at -.46 and -.48 for total and short term sexual partners.

Sneade and Furnham (2016) found a significant correlation of .22 between handgrip strength and number of lifetime sexual partners, a magnitude similar to what we see for physical attractiveness.

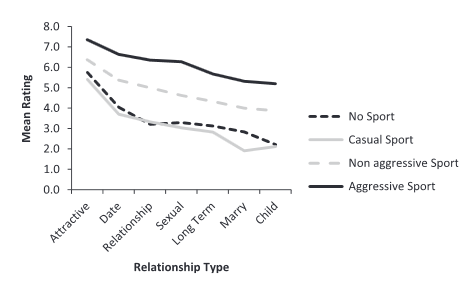

Although not measuring sexual partners specifically, research has also shown that men who play sports are rated as more attractive by women (Brewer & Howarth, 2012). This is not an effect of athletes being more attractive. In the experiment, the same photos of men were paired with a description that they either: don’t play sports, play sports casually, or play sports competitively. The same men are rated as more attractive when women think they play a competitive sport. Further, this effect persists for every type of relationship (consistent with the most current literature on female mate preferences, which indicate they are actually quite similar for both short and long term mating contexts).

Faurie et al. (2004) similarly found that student athletes had a higher number of sexual partners. Consistent with Brewer & Howarth (2012), this effect was larger for student athletes who were more competitive. The average number of sexual partners for non-athletes was 1, while the average for athletes was 2.41.

Peters et al. (2008) found that testosterone predicted the cumulative number of lifetime sexual partners and a composite score of mating behavior (relationships, casual sex, etc.). Additional research on the effect of testosterone on mating success can be found in The Testosterone Blackpill.

The personality construct of the Dark Triad also predicts a higher lifetime number of sexual partners for men (Borráz-León & Rantala, 2021; Jonason et al., 2009). Very consistently, this is one personality construct that we see predicts sexual risk behavior.

This is just a very brief overview. You could write a book on all of the different traits that predict promiscuity. By no means is this a comprehensive list. The take-home point is that pretty much every personality trait that you imagine is related to mating success probably does predict mating success. Further, they predict sexual behavior as well as physical attractiveness, if not more.

Why is the correlation low?

The point of all of this is not that physical attractiveness is meaningless in acquiring sexual partners. Let’s again imagine two men:

- Man A is really unattractive. He had sex once at 19 and has been single the rest of his life. His total partner count is 1.

- Man B is really attractive. He married his girlfriend at 19. His total partner count is 1.

These two men have had very different relationship trajectories, yet if all you looked at were sexual partner count it would seem the same. Attractive men may form relationships more easily, earlier, and potentially stay in them longer. The relationships might be better. Past research has found that women are more likely to orgasm in relationships with attractive men (Shackleford et al., 2000; Thornhill et al., 1995) and that physical attractiveness predicts higher relationship commitment, satisfaction, and intimacy (Sangrador & Yela, 2000; Meltzer et al., 2014). At the same time, research on this has been mixed, with some studies reporting that attractiveness predicts earlier relationship dissolution (Ma-Kellams et al., 2017).

Nature is not an equal playing field. Attractive men do have advantages. Yet, relationship formation means that attractive men are also pulled from the dating pool, or from the marketplace of casual sex. Rather than racking up a “body count,” most men and women follow a lifetime trajectory of serial monogamy. They form relationships for fairly long periods of time (not always for life, but sometimes, and often for many years) and have sex exclusively within those relationships (for example, see: How Many Sexual Partners Did Men and Women Have in 2021?).

This is contrary to our folk psychology. We commonly associate promiscuity with physical attractiveness. For example, Nedelec & Beaver (2014) found that photos of attractive men were more likely to be judged as having had many sexual partners (they didn’t) and more likely to have STDs (they didn’t).

At the end of the day, all it takes to see a low correlation between physical attractiveness and sexual partner count is this: men who are mid can still accumulate many sexual partners, while highly attractive men can also form long term relationships.

This does, however, make sexual partner count a pretty bad measure of who the “top men” are, at least if you’re trying to infer from it who the most physically attractive men are.

References

Amos, N., & McCabe, M. (2017). The importance of feeling sexually attractive: Can it predict an individual’s experience of their sexuality and sexual relationships across gender and sexual orientation?. International Journal of Psychology, 52(5), 354-363.

Bogaert, A. F., & Fisher, W. A. (1995). Predictors of university men’s number of sexual partners. Journal of Sex Research, 32(2), 119-130.

Bogaert, A. F., & Sadava, S. (2002). Adult attachment and sexual behavior. Personal Relationships, 9(2), 191-204.

Borráz-León, J. I., & Rantala, M. J. (2021). Does the Dark Triad predict self-perceived attractiveness, mate value, and number of sexual partners both in men and women?. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110341.

Boothroyd, L. G., Gray, A. W., Headland, T. N., Uehara, R. T., Waynforth, D., Burt, D. M., & Pound, N. (2017). Male facial appearance and offspring mortality in two traditional societies. PLoS One, 12(1), e0169181.

Brewer, G., & Howarth, S. (2012). Sport, attractiveness and aggression. Personality and individual differences, 53(5), 640-643.

Claxton, S. E. (2012). Diversity of Sexual Experience in College Students: The Role of Personal Characteristics (Doctoral dissertation, Kent State University).

Faurie, C., Pontier, D., & Raymond, M. (2004). Student athletes claim to have more sexual partners than other students. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25(1), 1-8.

Fink, B., Brewer, G., Fehl, K., & Neave, N. (2007). Instrumentality and lifetime number of sexual partners. Personality and Individual differences, 43(4), 747-756.

Foo, Y. Z., Simmons, L. W., & Rhodes, G. (2017). The relationship between health and mating success in humans. Royal Society Open Science, 4(1), 160603.

Foo, Y. Z. (2016). The Relationship between Facial Appearance and Health in Humans.

Gangestad, S. W., & Thornhill, R. (1997). The evolutionary psychology of extrapair sex: The role of fluctuating asymmetry. Evolution and Human Behavior, 18(2), 69-88.

Hill, A. K., Hunt, J., Welling, L. L., Cardenas, R. A., Rotella, M. A., Wheatley, J. R., … & Puts, D. A. (2013). Quantifying the strength and form of sexual selection on men’s traits. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34(5), 334-341.

Hughes, S. M., Dispenza, F., & Gallup Jr, G. G. (2004). Ratings of voice attractiveness predict sexual behavior and body configuration. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25(5), 295-304.

Hughes, S. M., & Gallup Jr, G. G. (2003). Sex differences in morphological predictors of sexual behavior: Shoulder to hip and waist to hip ratios. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24(3), 173-178.

Jonason, P. K., Li, N. P., Webster, G. D., & Schmitt, D. P. (2009). The dark triad: Facilitating a short‐term mating strategy in men. European journal of personality, 23(1), 5-18.

Jones, B. T., Jones, B. C., Thomas, A. P., & Piper, J. (2003). Alcohol consumption increases attractiveness ratings of opposite‐sex faces: A possible third route to risky sex. Addiction, 98(8), 1069-1075.

Kniffin, K. M., & Wilson, D. S. (2004). The effect of nonphysical traits on the perception of physical attractiveness: Three naturalistic studies. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25(2), 88-101.

Kordsmeyer, T. L., Hunt, J., Puts, D., Ostner, J., & Penke, L. (2017). Preprint” The relative importance of intra-and intersexual selection on human male sexually dimorphic traits”.

Krishnamurti, T., Davis, A. L., & Fischhoff, B. (2020). Inferring sexually transmitted infection risk from attractiveness in online dating among adolescents and young adults: Exploratory study. Journal of medical Internet research, 22(6), e14242.

Leenaars, L. S., Dane, A. V., & Marini, Z. A. (2008). Evolutionary perspective on indirect victimization in adolescence: The role of attractiveness, dating and sexual behavior. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 34(4), 404-415.

Lynn, C. D., Pipitone, R. N., & Keenan, J. P. (2014). To thine own self be false: self-deceptive enhancement and sexual awareness influences on mating success. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 8(2), 109.

Ma-Kellams, C., Wang, M. C., & Cardiel, H. (2017). Attractiveness and relationship longevity: Beauty is not what it is cracked up to be. Personal relationships, 24(1), 146-161.

McClintock, E. A. (2011). Handsome wants as handsome does: Physical attractiveness and gender differences in revealed sexual preferences. Biodemography and Social Biology, 57(2), 221-257.

Meltzer, A. L., McNulty, J. K., Jackson, G. L., & Karney, B. R. (2014). Men still value physical attractiveness in a long-term mate more than women: Rejoinder to Eastwick, Neff, Finkel, Luchies, and Hunt (2014).

Nedelec, J. L., & Beaver, K. M. (2014). Physical attractiveness as a phenotypic marker of health: an assessment using a nationally representative sample of American adults. Evolution and Human Behavior, 35(6), 456-463.

Pátková, Ž., Schwambergová, D., Třebická Fialová, J., Třebický, V., Stella, D., Kleisner, K., & Havlíček, J. (2022). Attractive and healthy-looking male faces do not show higher immunoreactivity. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 18432.

Peters, M., Simmons, L. W., & Rhodes, G. (2008). Testosterone is associated with mating success but not attractiveness or masculinity in human males. Animal Behaviour, 76(2), 297-303.

Raffaelli, M., & Crockett, L. J. (2003). Sexual risk taking in adolescence: the role of self-regulation and attraction to risk. Developmental psychology, 39(6), 1036.

Rhodes, G., Simmons, L. W., & Peters, M. (2005). Attractiveness and sexual behavior: Does attractiveness enhance mating success?. Evolution and human behavior, 26(2), 186-201.

Rhodes, G., Lie, H. C., Thevaraja, N., Taylor, L., Iredell, N., Curran, C., … & Simmons, L. W. (2011). Facial attractiveness ratings from video-clips and static images tell the same story. PloS one, 6(11), e26653.

Sangrador, J. L., & Yela, C. (2000). ‘What is beautiful is loved’: Physical attractiveness in love relationships in a representative sample. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 28(3), 207-218.

Seffrin, P., & Ingulli, P. (2021). Brains, brawn, and beauty: The complementary roles of intelligence and physical aggression in attracting sexual partners. Aggressive behavior, 47(1), 38-49.

Shoup, M. L., & Gallup, G. G. (2008). Men’s faces convey information about their bodies and their behavior: What you see is what you get. Evolutionary Psychology, 6(3), 147470490800600311.

Stelzer, C., Desmond, S. M., & Price, J. H. (1987). Physical attractiveness and sexual activity of college students. Psychological Reports, 60(2), 567-573.

Shackelford, T. K., Weekes-Shackelford, V. A., LeBlanc, G. J., Bleske, A. L., Euler, H. A., & Hoier, S. (2000). Female coital orgasm and male attractiveness. Human Nature, 11, 299-306.

Sneade, M., & Furnham, A. (2016). Hand grip strength and self-perceptions of physical attractiveness and psychological well-being. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 2, 123-128.

Thornhill, R., Gangestad, S. W., & Comer, R. (1995). Human female orgasm and mate fluctuating asymmetry. Animal behaviour, 50(6), 1601-1615.

Thornhill, R., Gangestad, S. W., Miller, R., Scheyd, G., McCollough, J. K., & Franklin, M. (2003). Major histocompatibility complex genes, symmetry, and body scent attractiveness in men and women. Behavioral Ecology, 14(5), 668-678.

Townsend, J. M., & Levy, G. D. (1990). Effects of potential partners’ physical attractiveness and socioeconomic status on sexuality and partner selection. Archives of sexual behavior, 19, 149-164.

Van Dongen, S., & Sprengers, E. (2012). Hand grip strength in relation to morphological measures of masculinity, fluctuating asymmetry and sexual behaviour in males and females. Sex Hormones. InTech, 293-306.

Van Dongen, S. (2011). Associations between asymmetry and human attractiveness: Possible direct effects of asymmetry and signatures of publication bias. Annals of human biology, 38(3), 317-323.

Weeden, J., & Sabini, J. (2007). Subjective and objective measures of attractiveness and their relation to sexual behavior and sexual attitudes in university students. Archives of sexual behavior, 36, 79-88.

Wiederman, M. W., & Hurst, S. R. (1998). Body size, physical attractiveness, and body image among young adult women: Relationships to sexual experience and sexual esteem. Journal of Sex Research, 35(3), 272-281.

11 comments

Male attractiveness goes beyond the number of sexual partners one has had. True appeal lies in kindness, respect, and genuine connections. Let’s prioritize meaningful connections over mere statistics, embracing the beauty of diverse qualities that make individuals truly attractive.

Bluepill

To be really honest i don’t think this research is in the right time give the majority of sources being old, trully old, the sexual behavior have shifted a lot specially with dating apps taking now a huge chunck of casual sex relationships starters, some sources are from 2021 and thats good, but we need all the old data to be renewed. Online dating favours a lot more the attractivness.

Will you accept the result if up to date data says the same, or will you find another way to attack the results to not have to change your predefined world view?

Very interesting data. It would be interesting to see some more data about the most unattractive men, especially young men. To see whether or not being super ugly completely excludes you from any chance of a relationship. People have strong opinions about involuntary celibates (I don’t mean the misogyny stuff I just mean the idea that some people are too ugly to have sex), but it’s hard to find real data to see how right or wrong they are.

I think there is a typo here. You put in shoulder-to-height ratio when the study you cited concerned shoulder-to-hip and shoulder-to-waist ratios.

Could you tell me how you got a correlation coefficient of -0.16 from Pátková et al? I couldn’t find it.

It would have interesting if datas show elsewhere… This means that humans were the only mamals that chose their partners solely based on their looks which can be extreamly dangerious in evoultion aspect becuase pregancy takes a lot of time plus a new born infant needs a lot of supports for a long time from their parents where the father personalty is crushel.

This black pill crap probebly works among birds, lizards, snakes but not among mamals.

Some black pillers argue that we are no longer in the cave and women can chose whatever they want… This doesn’t eredic million and million of years evoultion.