Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

Psychologist Andrew Thomas recently ran a poll and asked: “have you ever felt a profound and enduring state of unhappiness, uneasiness, and discontent about your singlehood?” The phrasing of the question was intended to mirror that of clinical dysphoria. 55.1% of men and 44.9% of women responded yes. Thomas has written about the emerging concept of dysphoric singlehood and its manifestations in modern society. The results of this poll further indicate that feelings of dysphoric singlehood are a common experience. A large number of people, in particular young adults, have been single, lonely, and unhappy.

Additional recent evidence has shown trends of a “loneliness crisis” and a “mating crisis.” A representative survey found that one in five teens felt lonely often and that feeling left out increased from 13% in 2018 to 30% in 2022 (HBSC, 2022). Jean Twenge, a psychologist (with an h-index of 103) who studies generational differences and development, has also observed this trend (Twenge et al., 2021). In a longitudinal study of teens from 37 countries, consisting of over one million teens, Twenge et al. found a substantial increase in loneliness between 2012 to 2022.

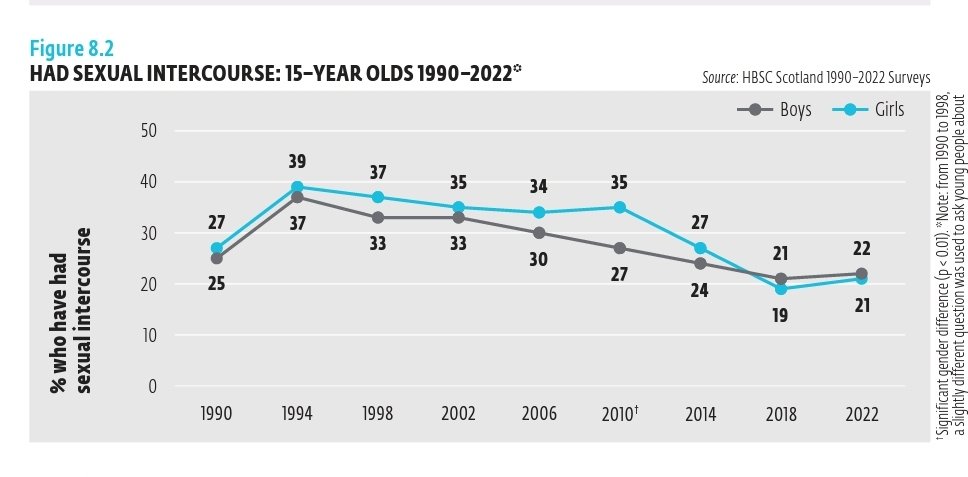

A recent representative sample from the Center for Disease Control (CDC) (2021) also identified a trend in increased loneliness and poor mental health in teen girls. Additionally, teen sex for boys and girls decreased. In fact, most risk behavior decreased (consistent with the research of Twenge et al.; the younger generations are becoming more risk averse). This is also seen in the HBSC report. Teens are smoking less, using drugs less, drinking less, and getting in fewer physical fights. Despite this, mental health outcomes became worse for both boys and girls. Ball et al. (2023) similarly found a long term decline in risk behavior in teens from 1990 to 2019. Teens were using less alcohol, engaging in less juvenile delinquency, and having less sex. Young men and women also now attend fewer in-person gatherings (e.g. house parties). Additionally, young adults have fewer friends and smaller friend groups than in the past (Cox, 2021).

Below are sexual behaviors for teen boys and girls longitudinally in the HBSC dataset:

Why should we look at preadult teens? In the discussion of single and sexless young adults we tend to think only of those past age 18. We might not even want teens having a lot of sex, but we expect young adults to. If emerging adults aren’t having sex we wonder if something may be wrong. However, the developmental trajectory of a pubescent human being doesn’t flip a switch at year 18. Teens have sex, too (and when they do we hope it’s with other teens and not adults). Generational differences may be observed in the youngest of the generational cohort (Zoomers). What we see is that trends of adult singledom and sexlessness are beginning in the teens.

Past research has also linked lower teen and adult sex to risk averse behavior (see the second section of Are 27% Of Young Men Really Virgins?). Sex can be risky business. Early relationships and love can be risky in their own way, too.

Further, nonsexual risk behaviors compound to produce sexual outcomes or greater sexual frequency in a population. For example, abstinence from alcohol explains as much as 30% of the variance in being sexless over the course of a year (South & Lei, 2021). Risk aversion is also reflected in dating-related approach behavior. In a recent survey, 53% of single men said that the fear of being called “creepy” reduced their likelihood of interacting with women. Consistent with this, a recent Pew survey of singles found half of single men between age 18-30 were voluntarily single. An even higher percentage of single women were voluntarily single. The youth may be dropping out. It might be driven, in part, by fear.

Approaching People To Date, In Person

Approaching someone to date may seem like the riskiest thing that you can do. Indeed, for some, discourse around asking a woman for a date has become practically hysterical. Yet, you also won’t meet anyone if you don’t approach. Much has been said about the rise of incels, voluntary/involuntary singles, and the decline in young adult sexual behavior. Could one contributing factor be a generational shift toward risk aversion and a decline in personal approaches?

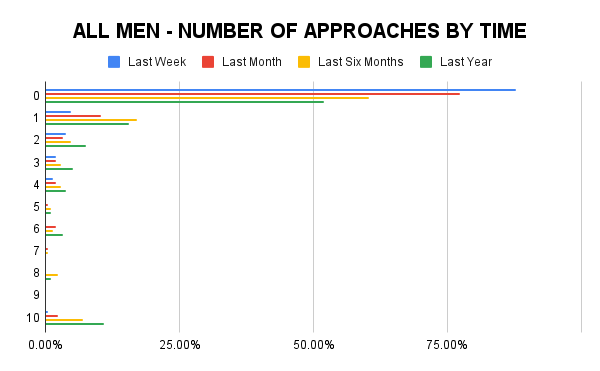

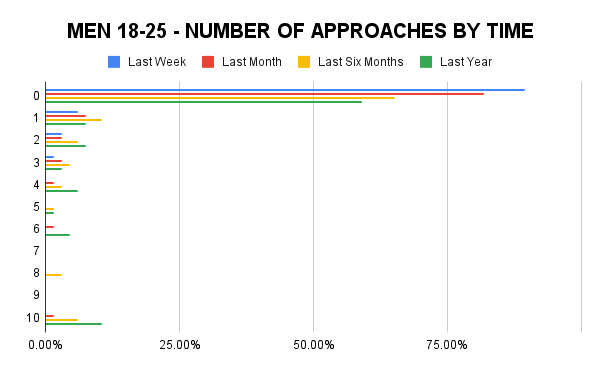

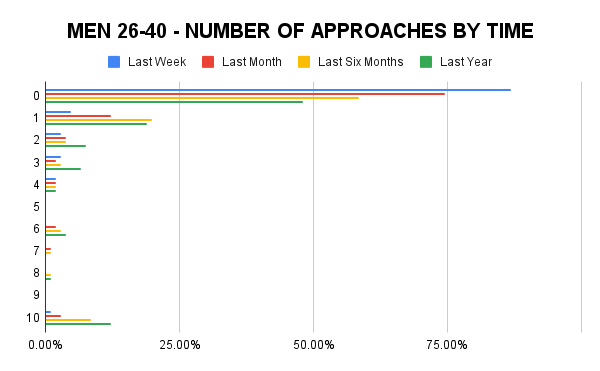

I collected a convenience sample from social media (N = 368) to test a few of these questions. Below are the results.

Approaches By Time

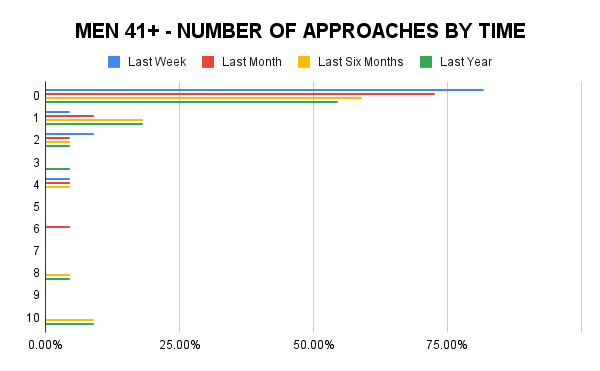

The charts above are for single men. About half of single men have not approached a woman in person within the past year. This is true for each age group, but it does vary. For example, 59% of men within the 18-25 age group (Zoomers) have not approached someone in the past year. 48% of men in the 26-40 age group (Millennials) have not. Millennials are approaching more, consistent with the hypothesis of a generational shift in risk aversion (Zoomers being more risk averse). A substantial percentage of all men have not approached anyone within the past month (81.81% Zoomers; 74.52% Millennials).

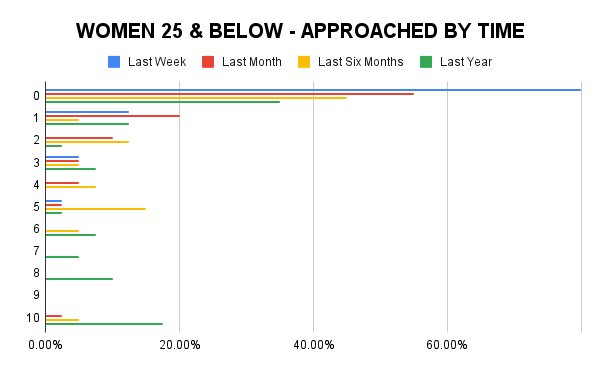

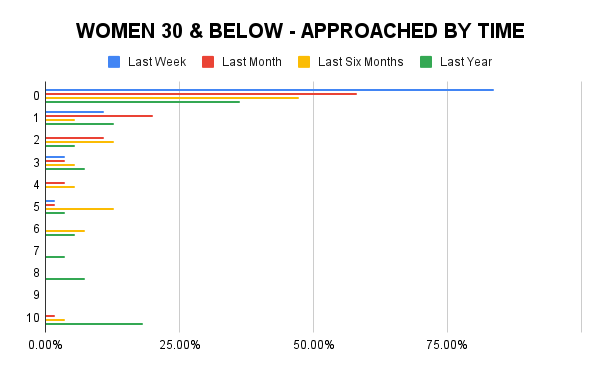

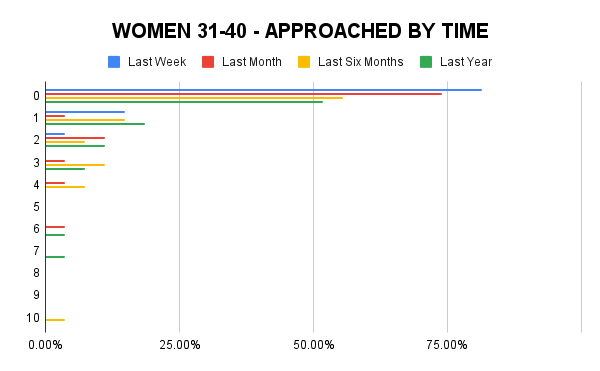

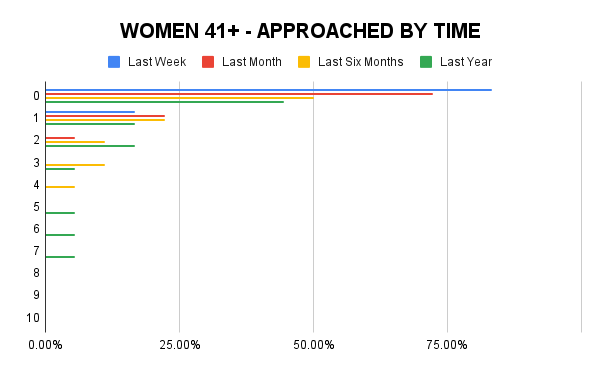

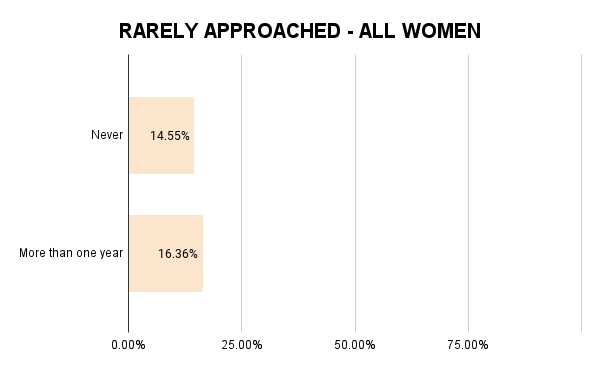

Above are charts for female participants who reported being approached (or not) in person for a date. As men conventionally approach, I included all women in my sample. Men who approach a woman in person may not know if the woman is single or not. The age groups are a little different, because you may also wonder if young women get approached more. For women age 25 and below, 55% have not been approached within the past month and 35% have not been approached within the last year. The results don’t shift much for women age 30 and below (which includes the 25 and below cohort). They do go up for the female age 31-40 group: 74% have not been approached within the past month while 52% have not been approached within the past year. As you might expect, women get approached less in their 30s than in their 20s.

Why might that be? The mate pool past age 30 is much smaller; most people are in relationships and thus fewer single men of a similar age exist to approach. Men on average don’t date up in age (and women don’t show preferences for younger men on average, either). Peer groups shrink with age (they were already small to begin with). Fewer 30-year-olds are in school. Many have begun a home-work-home routine. There is also a relationship between female age and physical attractiveness.

Also of note for the female charts is that women, even when approached, are being approached rather infrequently.

Do Women Want To Be Approached?

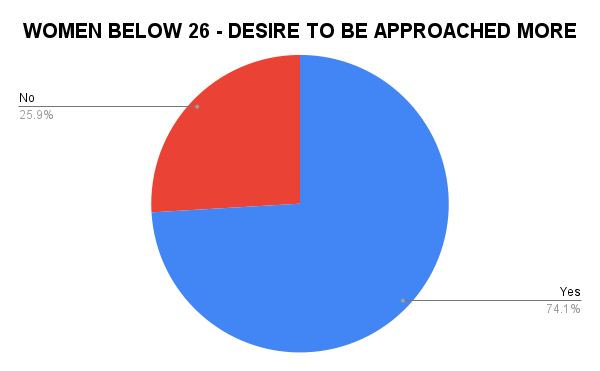

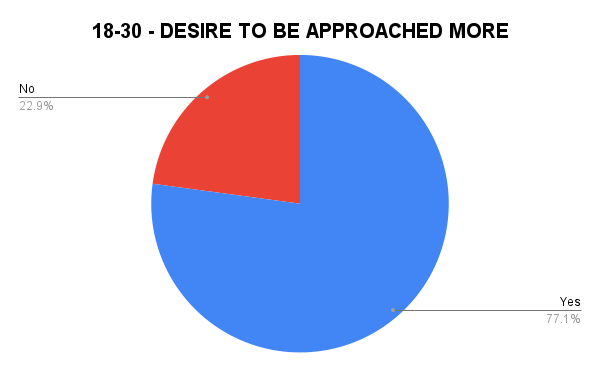

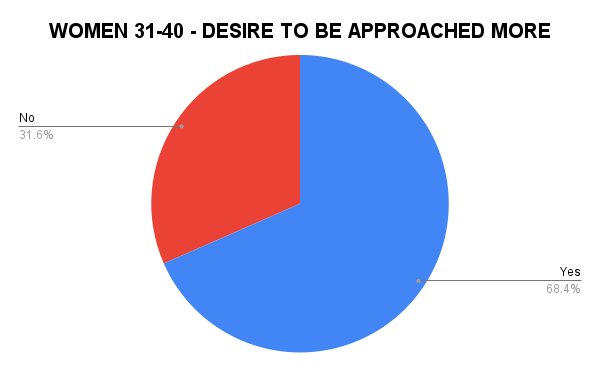

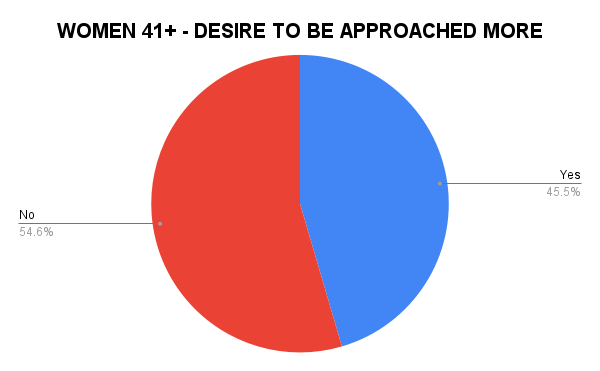

Do women want to be approached for a date in person? You may have seen both men and women assert that women do not. According to my results, most women do. A similar percentage of women in their 20s and 30s also want to be approached. However, the desire to be approached drops off for women in the age 41 and above group. The oldest cohort of women wish to be approached less.

74% of women aged 25 and below want to be approached more; 77% in the full 18-30 cohort. 68% wish to be approached more between 30-40, while for women 41 and older 45% wish to be approached more.

The results show a trend where as age increases the desire to be approached declines.

Do Men Regret Not Approaching?

Mostly, yes. And regret is stable across age cohorts. 60% of Zoomers and 64% of Millennials wish they had approached more women. 63% of single men in the age 41 and above age group do as well. The regrets that men have for missing a shot persist across the lifespan. It’s an ubiquitous experience for men: hesitating to talk to a woman and wishing you had.

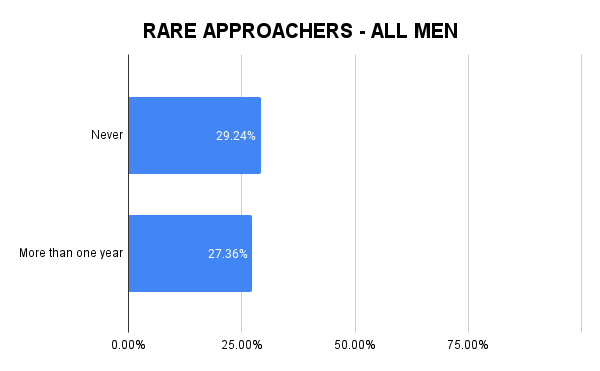

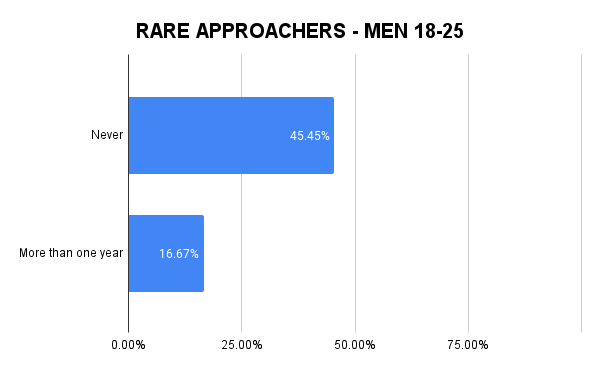

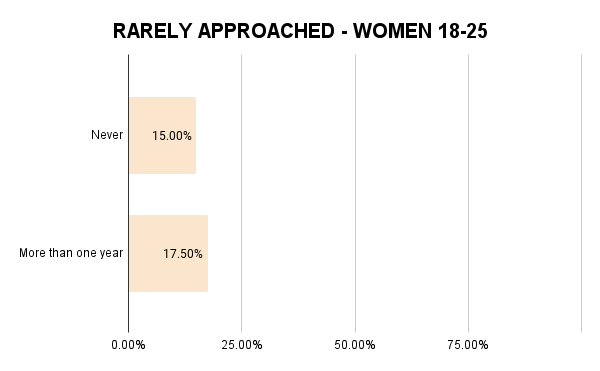

Some Men Never Approach; Some Women Never Get Approached

A sizeable minority of men are not approaching women at all. In the entire dataset, 29% of men said they never approached a woman in person before. 27% said it had been more than one year. This was larger for men in the age 18-25 group: 45% had never approached a woman in person. This is again consistent with the hypothesis of a generational risk aversion trend in Zoomers. 17% had not approached a woman in more than one year. “Never” and “more than one year” are discrete groups. This means that about half of all single men in my dataset are effectively not approaching women for dates in person.

Should You Be Afraid To Approach?

Another popular belief is that men should be afraid to approach women due to potential ramifications. These fears manifest most strongly for workplace, social, or legal consequences. The #MeToo movement may have made the possibility of this more salient for men as well. How true to life is the risk?

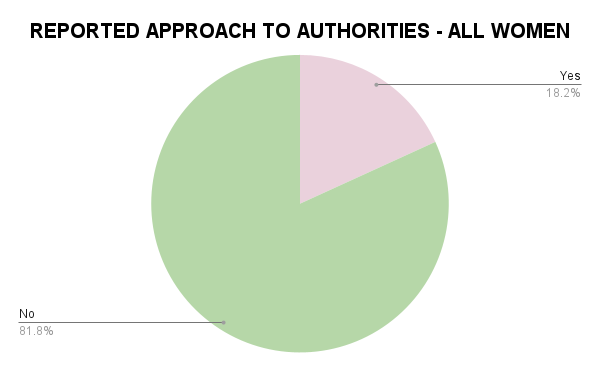

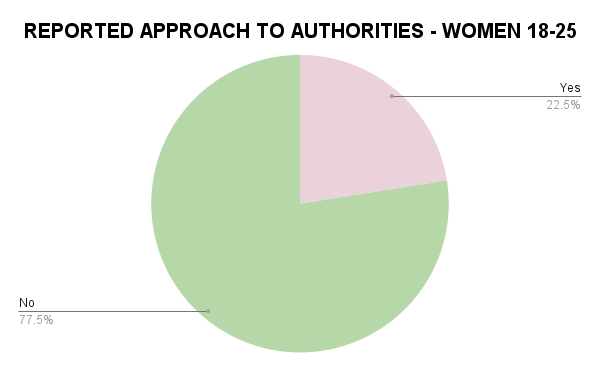

About 18% of all women in the sample and 22% of women in the age 18-25 group stated that they reported someone to an authority figure for approaching them sexually or romantically. The youngest cohort is a little more likely to place a report, but the difference is small. It probably hasn’t become more “dangerous” to approach a woman.

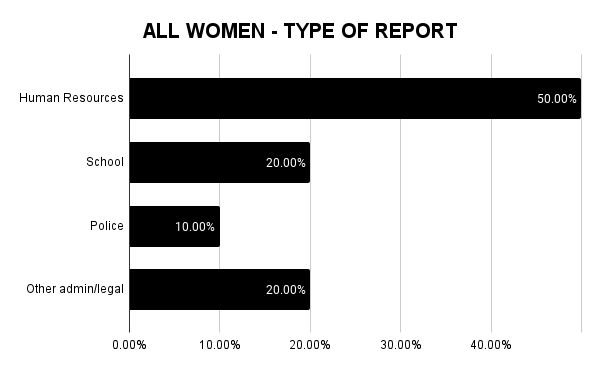

When a woman has sought help or made a report due to a sexual advance, what kind of reports have they made?

Most reports were to human resources, indicating a romantic approach in the workplace. Conventional wisdom says that it’s bad to have a workplace romance. Additionally, many work environments have explicit rules that prohibit it. Nonetheless, work still remains one of the top ways couples meet. Keeping that in mind, it is important to be well attuned to when romantic overtures are wanted or unwanted.

This is very important — I don’t know the circumstances around any of these reports at all. Some readers will interpret this as capricious and a justification for their fear of approaching women. I have seen fear of interpersonal romantic interaction framed as “logical” given potential consequences. However, most of these likely represent sexual harassment or obvious violations of social norms and expectations. It’s not random. How and where you ask a woman for a date will determine how your interaction goes. You’re not going to go to jail for asking a woman politely if she would like to have a coffee.

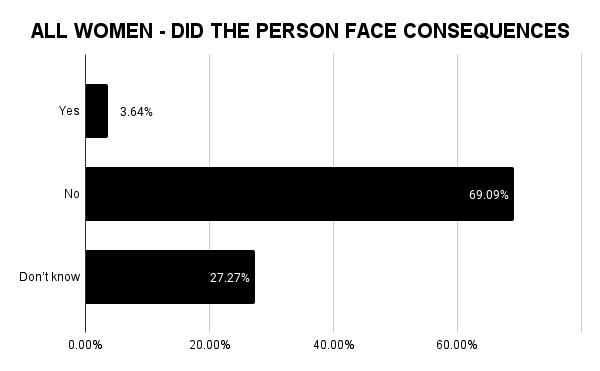

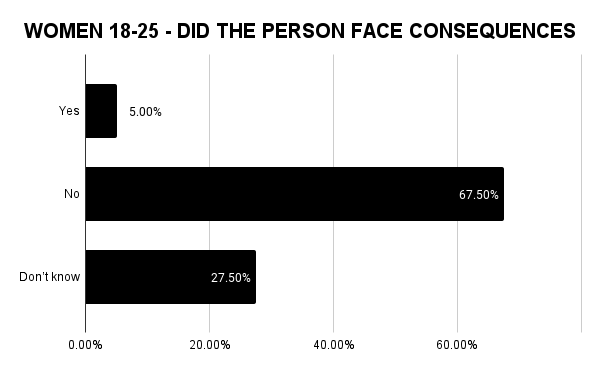

All of the report figures are higher than I had expected to see in my results. I also asked participants if the person they reported for approaching them faced any consequences. Almost all of the women said no, or that they did not know. This may also indicate that it hasn’t gotten more dangerous, despite trends like #MeToo and greater awareness around sexual harassment. Men probably aren’t facing a lot of consequences (even in situations where they might really deserve them).

Why Don’t Men Approach Women More?

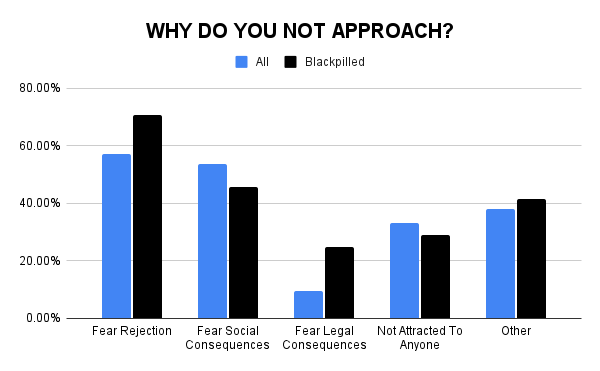

I asked single men why they did not approach women for dates in person. I also asked men about blackpill subculture identification. The blackpill is an ideology closely related to, and held, by incels. Incels.wiki defines it as “a philosophy that argues that physical attractiveness is the most critical factor in determining men’s dating success.”

The top reasons for not approaching women were a fear of rejection and a fear of social consequences. These fears have always existed. They are timeless. As a man it is normal to feel them.

However, there was a difference between groups: blackpilled men had a higher fear of rejection and a higher fear of legal consequences. Fear of legal consequences was a low motive for most men. Nonetheless, a sincere belief in legal repercussions (jail, a stigmatizing criminal record) may be an especially strong motive. At 9% for the non-blackpilled male sample, this may also represent one belief that keeps some men single.

Additionally, not being able to find a woman attractive enough to approach was indicated for about 30% of men. Much discourse around young singles frames them as being involuntarily excluded from the mating market. However, simply not having anyone that you desire in immediate proximity may explain some singledom outcomes. Why might this be? An imbalanced sex ratio in one’s immediate environment may contribute. Work in a male-dominated field may give you little exposure to attractive women. Being too busy may limit your chances of interaction. Self-isolation and the decline in friend group size may limit exposure to attractive members of the opposite (or same) sex. We also see rising trends of obesity in young adults. Despite the body positivity movement, certain body types are still conventionally preferred and this may limit one’s pool of attractive prospects.

Why Don’t Women Want To Be Approached?

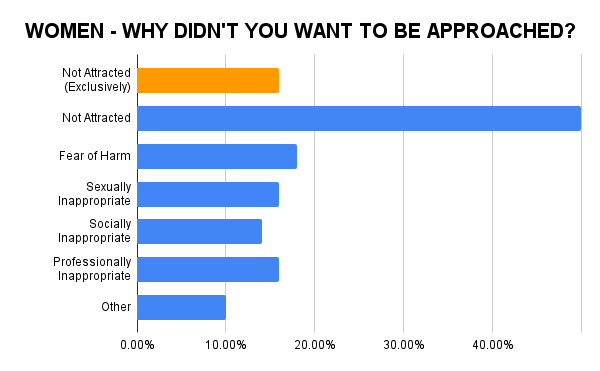

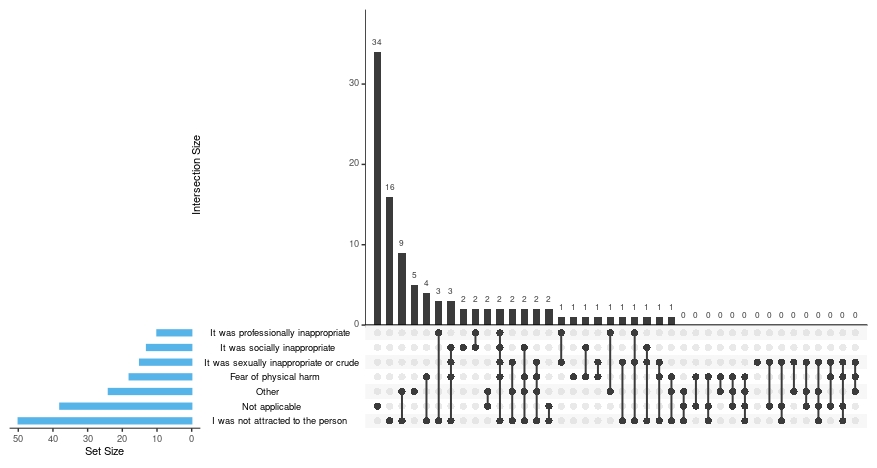

For women who were approached in person for a date, but didn’t desire to be, the top reason indicated was not finding the man attractive. In this response, women were able to select multiple options. Fear of harm, sexual, social, and professional inappropriateness were often selected in conjunction by many female respondents. These will often go hand-in-hand. What is sexually inappropriate may also be professionally inappropriate, for example.

I have updated this chart (Jan 4, 2025). As noted above, selections were not mutually exclusive. Only 16% of women cited “not attractive,” exclusively, as a reason for not wishing to be approached. The remaining 84% of women selected “not attracted” in conjunction with one or more of the other options or some combination of the other options without “not attracted.”

I should have picked a better data visualization for this, such as an UpSet plot. So, here is the UpSet plot:

34% of women selected “not applicable,” so either they had not been approached or they found no approaches objectionable. The largest set was not being attracted, but this frequently overlapped with other reasons.

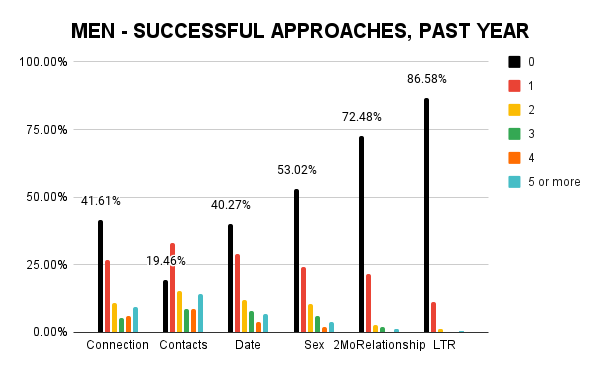

Approaching In Person – It Still Works Remarkably Well

Of the men who did approach women in person over the last year, a substantial number had success. I labeled the percentages of men with zero success to compare. A minority of men, 41.61%, said that they did not make a romantic connection. Most men who approached in person received contact information or went on a date. A little less than half had sex.

However, only about 13% ended up forming a long term relationship. This is expected. As you follow the trajectory from a phone number exchange to a long term relationship you will see attrition at every stage.

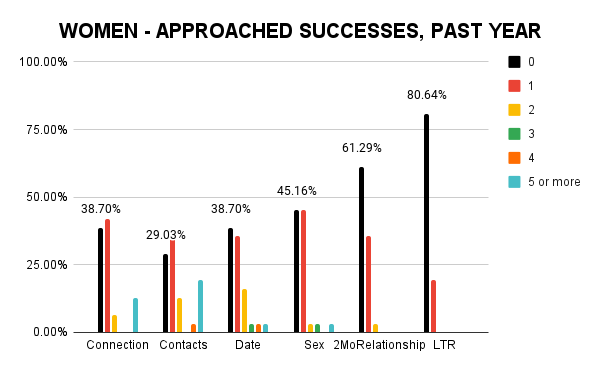

The pattern was similar for women who had been approached. Women also had more successful outcomes being approached. In this data we also see the trend of relatively low promiscuity I have written about before. Of women who had sex with a man who approached them, most had sex with only one person within the past year.

Risk Aversion & Approach: Tests

I used three items from the general risk propensity scale (GriPS) (Zhang et al., 2019) to measure risk aversion.

I found no statistically significant difference in risk aversion scores between male Zoomers (8.57) and male Millennials (8.67) (t = -0.21208, df = 138.6, p-value = 0.8324). Age was also not correlated with risk seeking scores (r = .06, t = 1.03, df = 263, p-value = 0.304). However, we might expect that there should be a difference. We expect young adults to score higher on risk-seeking measures. A consistent trend in human behavior is that young adults, in particular men between the ages of 16 and 25, should be less risk averse. This is most clear in the age-crime relationship; most crime is committed by young men between these ages.

I did not find a significant difference between men in relationships (9.22) and single men (8.86) (t = 0.89009, df = 91.345, p-value = 0.3758). Men seeking relationships also did not score differently in risk aversion from those who did not (t = -1.3415, df = 257.04, p-value = 0.1809).

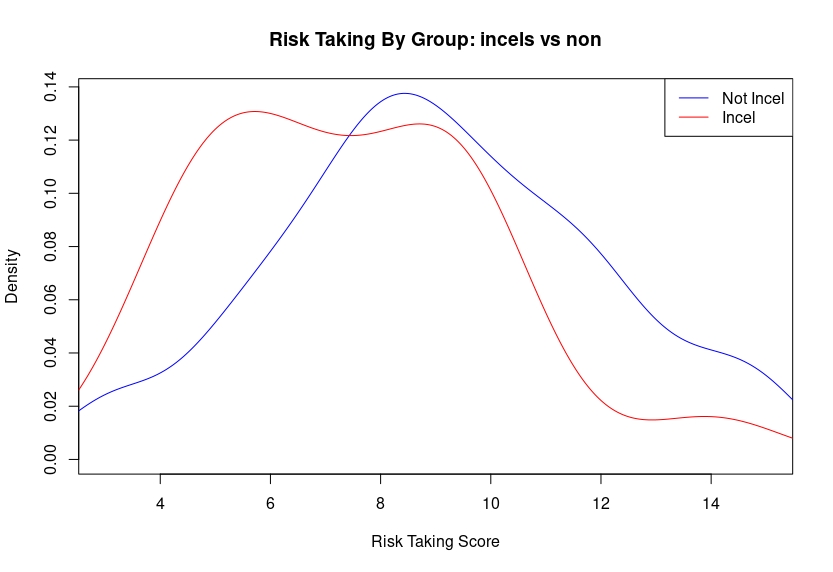

However, men who identified as incels did score lower in risk propensity (7.45) than men who did not (9.06) (t = 2.665, df = 23.22, p-value = 0.01377). Men who identified as blackpilled (7.15) also scored lower than men who did not (9.14) (t = 2.7969, df = 31.149, p-value = 0.008765). The Cohen’s d for the respective comparisons .58; incels and blackpilled men overlapped highly.

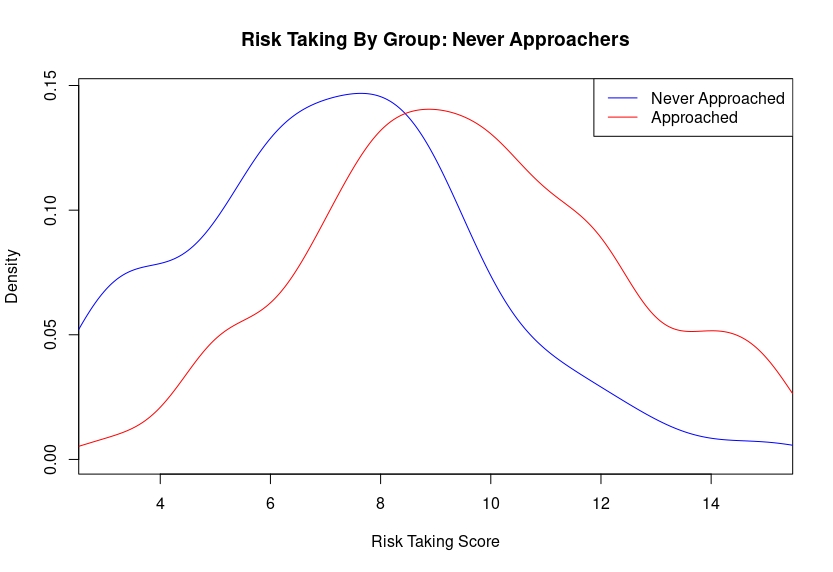

Above shows the distribution of risk propensity for incels and non-incels. Below is the chart for men who have never approached a woman for a date in person. As mentioned in the previous section, some men rarely or never approach women. These men are also more risk averse than men who do approach women in person for dates (7.16 vs 9.55, d = .88, t = 6.3373, df = 121.14, p-value = 4.162e-09).

Discussion

Individual differences in risk aversion, particularly in the context of a generational shift, may represent an underexamined contribution of young adult singledom. Populations of men that are less likely to approach women for dates in person may be more risk averse. Men who are blackpilled fear rejection and legal consequences more. Zoomers are less likely to have ever approached a woman. Men who never approach scored lower in risk propensity.

However, asking women for dates in person still works. A majority of women, particularly those in the youngest age groups, wished that men approached them for dates more. Men who did approach women for dates did prettty well, with most having made a romantic connection in the past year.

A few limitations: as with most samples in psychology this is nonrepresentative. There are populations where approaching women for dates in person may be more or less frequent. I suspect my sample was more likely, rather than less likely, to approach women for dates in person. We can’t know for sure. Nonetheless, you can compare the charts of female approachees with male approachers. A substantial number of women are not being asked for dates in person over the course of one year. Those who are asked also get asked infrequently.

I used only three items from the GRiPS to measure risk aversion. This will reduce its power to detect an effect. I did this because I thought the items on the scale were too similar, essentially asking the same question in multiple ways, which I thought might inflate the effect.

My sample was also not as large as I would have liked, particularly for comparing subgroups. However, the nonsignificant results were in the direction of the expected trend: Zoomers scored lower in risk propensity than Millennials; single men scored lower in risk propensity than men in relationships. Even with a small sample I was able to detect an effect for my incel/blackpill and “never approach” groups. With a larger sample I think you might be able to achieve statistical significance for young single men being more risk averse as well.

References

Ball, J., Grucza, R., Livingston, M., Ter Bogt, T., Currie, C., & de Looze, M. (2023). The great decline in adolescent risk behaviours: unitary trend, separate trends, or cascade?. Social Science & Medicine, 115616.

Cox, D. (2021). Men’s Social Circles are Shrinking. https://www.americansurveycenter.org/why-mens-social-circles-are-shrinking/

CDC (2021). YOUTH RISK BEHAVIOR SURVEY

HBSC (2022). HEALTH BEHAVIOUR IN SCHOOL-AGED CHILDREN: WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION COLLABORATIVE CROSS-NATIONAL STUDY (HBSC)

South, Scott J., and Lei Lei. “Why Are Fewer Young Adults Having Casual Sex?.” Socius 7 (2021): 2378023121996854.

Twenge, J.M., Haidt, J., Blake, A. B., McAllister, C., Lemon, H. & Le Roy, A. (2021). Worldwide increases in adolescent loneliness. Journal of Adolescence, 93, 257-269.

Zhang, D. C., Highhouse, S., & Nye, C. D. (2019). Development and validation of the general risk propensity scale (GRiPS). Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 32(2), 152-167.

45 comments

Interesting stuff. Another way to interpret the data is that being well-connected mitigates risk.

When you’re part of the in-group, it’s more socially risky to avoid smoking, alcohol, drugs, and fights. At the same time, being part of the crowd greases the wheels when it comes to approaching. Not only do you witness the people you identify with scoring, you’re recognized as part of the crew and thus have the social proof to back up your approach. If she does turn you down, she’s at least more likely to give you a softer landing than she might an incel whose approach makes her uncomfortable since he has no street cred.

The success of approaching could very well reflect people being conscious of their own social standing. Those with the aforementioned proof will approach because they already know they tick most of the boxes and thus that their chances of success are quite high whereas, for someone with the standing of an incel, it would be like applying for a job seeking someone with a Master’s degree and 5+ years of experience when you only have a GED; it’s not literally impossible, but it would require a level of salesmanship that a person on that level would be unlikely to possess.

I can’t help thinking that in this whole discourse there’s a conflation between two very different fears – the fear of being rejected versus fear of being reported.

You won’t get reported unless you’re actually harassing someone. But asking someone nicely and bring politely turned down – that can hurt too.

“You won’t get reported unless you’re actually harassing someone”

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7339691/Woman-falsely-accused-Good-Samaritan-sexual-assault-jailed.html

Relationships provide stereotypical benefits to the man and woman. For example, the man may get physical intimacy while the woman may get attention and validation. Relationships are also costly, e.g. safety fears over women giving up physical intimacy, while the men are giving up time and money. With the rise of the online world, e.g. online shopping (rather than real world shopping) and online working (rather than going to the office), we are seeing that humans are also migrating their relationships online. For example, men have a relationship with OF / PHub etc and get what they need online. And women have a relationship with their IG and get likes, DM’s, attention and validation online. I don’t think relationships are declining. I think people are just substituting their relationship with actual human beings in real life (which comes with so many costs) with relationships with websites as the online world tends to be more convenient, more safe, and less costly. Having online relationships with websites may even be more superior to having a real world relationship with an actual human being in real life.

I think it would be interesting to ask if men KNOW how to approach women. We often attribute the avoidance of approaching to fears and lack of confidence. What if men just don’t know how to approach? That will explain the lack of confidence and fears.

I think, you are too quick into attributing the avoidance of approach to some personality qualities. In addition to questions on actually having skills to approaching, you could have asked about past experiences. If 40% of guys said they had a lot of failures, it would explain their passivity better than some risk-taking score.

Back when I was around 20, after a seemingly endless run of rejections, I ran an experiment where I approached ten women a week for ten weeks. I had 100 rejections. Does that count as a lot of failures?

and as always, women still normally will never approach a man, even if she is strongly attracted to him, desires a certain man, women still normally never approach men and that will likely remain the norm for all eternity.

Turns out women are the socially awkward ones with no game and an irrational fear of rejection then. And yet they get to judge how men do it. It’s the hypocrisy that makes it despicable.

I approached a lot of strangers and it really didn’t work for me at all. They were probably too beautiful in general, but approaching strangers in Germany really sucks. I got one date out of 50

I agree it is a numbers game, but if you belt in and accept you have to approach 50 to get one date, you can have success. If you are really serious about securing a partner, plan your social life around it. Every week, go to five places where there are lots of people, a variety of places: bars, cooking classes, meetings about a cause you care about, a wine sip and paint, church, etc. Every time, strike up a casual conversation with at least ten women. Don’t be all skeezy asking every woman on a date, just try to make a connection. Learn how to do this, and give yourself grace and permission to be rejected.

By the third week, you should be lined up to ask one out on a date.

do you know how emotionally exhausting and financially prohibitive that is?

There are several conceptual and methodological issues here.

For example, women may report zero approaches if they got approached by men whom they considered not in the dateable range, whether or not they were socioeconomic and psychophysiological matches. Incipient, polite approaches by “unremarkable”/”too old/young”/”ugly”/”poor”/”ick” -looking men are probably quickly forgotten by most women, especially if they were preoccupied with the general business of life at the time. That’d be human nature, to filter out noise. But I could be wrong: we need to find out.

Second. The paragraphs about women reporting approaches, if the data hold up, run entirely counter to your assertions that riskiness of making an approach is unchanged. The problem is tail risk, and I would now call that extreme.

HR did not have the same power in the 1980s (when I was young) as it does now. “Reported to HR” was not even a thing on a pie chart. (Ubiquitous cameras with the ability to show your faux pas to the whole world also did not exist.)

Even if the overall risk is now the same as ever, the tail risk (losing your job, being shunned by your social group, being unable to find another job in your field, crippling your career and future earnings) is now much, much higher for young men.

Would you go through a door if you knew that touching it gave you a 1 in 1000 chance of losing your arm up to the shoulder? Would you do it repeatedly, on a daily or weekly basis?

The salient risk men face is tail risk, not median risk. You casually dismiss tail risk with a link, but that web page has even worse problems than this one. The salience is the problem, not the actual statistics. (I’d be keen to see your ideas about how to fix the salience. Mine tend to be outside the Overton window.)

That’s one methodological problem (or possibly two, or more), in the framing of the study and interpretation of the results.

There is a second major methodological problem: using self-report. And worse: from memory. We know now how reliable that is. TLDR: not at all.

I haven’t really thought about it, but I have a niggling feeling there are other problems orthogonal to both of these.

To get actually useful results, and conclusions worth the pixels they are shown on, we need studies using revealed preference: watching what people do, not what they say. Video records of people going about their daily lives and their interactions. Preferably high-speed, so we can catch micro-expressions. Yeah, it’s a lot of work. Get stuck in!

Would you go through a door if you knew that touching it gave you a 1 in 1000 chance of losing your arm up to the shoulder? Would you do it repeatedly, on a daily or weekly basis?

I`d say its more 50-50 chance to be decapitated. This day and age its easy to get a brand and not recover. Only the negative will stick even if its false. So it`s better to assume the worse and stay safe.

It’s pretty simple to find out the truth, most men declare to not approach at all, therefore, most women don’t get approached. About the risk, it would be interesting to ask women how many of their assaulters and stalkers and harassers throught all their lifes have been convicted and then ask men how many times they faced real consequences for stalking, gropping, harassing women. Oh, wait, we already now, most assaulters don’t get convicted, the whole speech about losing everything for saying “hello, I thought you are pretty, would you like to date me?” to a female classmate is ridiculous.

“You’re not going to go to jail for asking a woman politely if she would like to have a coffee.”

Asking for a coffee, I don’t know, but certainly if you try being a Good Samaritan:

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7339691/Woman-falsely-accused-Good-Samaritan-sexual-assault-jailed.html

You were this close to saying false accusations don’t exist.

In actuality, those low % of “faced consequences” are telling since we are post-MeToo with greater-than-ever “awareness” of sex. harassment & assault.

That happened 5 years ago, 5 years and you all can’t stop clinging to that case.

Get new material

I’d say the fact that people are not approaching is not because people are becoming more risk averse, but because life in general is moving to the digital world, hence approaching in person comes down to showing off as creepy. People don’t spend much time with each other anymore. They spend it on social media.

Can you give more details on the “convenience sample” of 368 people that you got from social media? How did you find these survey respondents? If they are people who follow a Date Psychology social media account then I would expect this data to be heavily biased. I suspect that people who follow your accounts are more likely to be singles who are frustrated with dating and struggling, rather than people who are happily single. Thoughts?