The red pill of the manosphere has a love affair with evolutionary psychology.

Unfortunately, as we have written about in the past, the red pill has also gotten evolutionary psychology very wrong. We have also written that the red pill has a poor epistemology, similar to postmodernism. It has come up with little that is new, makes no predictions, and tests no hypothesis.

One quasi-novel idea from the red pill may be that of the alpha widow. This is effectively just re-describing rumination over past partners, but we can examine this anew. An alpha widow is created when a woman cannot secure a long-term relationship with a man of high “sexual market value.” This may have been an ex, or even a casual sexual partner, who sets a new standard for what that woman demands. After having her “alpha” in some context — even for as short as five minutes! — no other man will live up to her new standards. The “alpha” has psychologically and emotionally “widowed” the woman.

This actually isn’t too far-fetched an idea. We know some people get hung up on exes. People also compare current romantic partners to past partners, a form of social comparison. We also know individuals calibrate their mate choice preferences to their own mate value (Reeve et al., 2017) and that self-perceptions of mate value are shaped by past mating success.

That some men have encountered this in women is totally plausible and almost certainly the case. However, the question is not if women ever get hung-up on exes. Women occasionally do, as do men. The question, rather, is how common it is.

The problem is that the red pill struggles to understand base rates. Men do not stumble into the manosphere from having success with women. The red pill is a subculture of men who have had bad experiences with women and who do poorly with women in general.

To illustrate, imagine a subculture for men who believe that they have been abducted by UFOs. They have an experience as an abductee and they seek out others who share their experience. They speak with their friends on The UFOTalk Forum to swap stories. They go to a UFO convention and find a large number of men who, just like them, have been probed in the buttocks. In the end, they conclude that alien abductions are frequent and most men have an abduction experience.

This describes selection bias and confirmation bias. The men in the UFO abductee subculture are a self-selected group. They interact with others who share their beliefs; they don’t interact with the world at large. This exposes them to a disproportionately large number of UFO abduction experiences. They seek out information that confirms their existing beliefs while simultaneously dismissing information that is contradictory.

They might also erroneously conclude that UFO abductions are primarily a male phenomenon, given self-selection into male abductee communities. A new ideology emerges: “Aliens only abduct men.”

Together, selection bias and confirmation bias skew the perception of how common abduction experiences really are, as well as how many people share what they believe. They don’t form accurate beliefs on the prevalence of UFO abduction experiences. They extrapolate from their own experiences to populations who overwhelmingly do not share their experiences.

Men telling stories about alpha widows is predictable the same way that you can expect to find men telling stories about UFOs at the UFO convention. However, it does not seek to gather evidence nor does it follow the scientific method. It does not give you any real information. It is merely a recounting of “lived experiences.”

Research Aims

In the current research, we primarily aim to quantify the alpha widow experience for the first time. Given the gendered framing — the alpha widow is purportedly an exclusively female phenomenon — we also test for sex differences.

We also include a validated measure of self-deceptive denial (Paulhus, 1999) to test for social desirability bias, and/or an unwillingness to admit difficult feelings and thoughts about oneself.

Finally, we test for proximity effects on rumination and feelings about past partners. We expect participants who have had recent break-ups, or who have had a more recent casual sex partner, to score higher on measures assessing their thoughts and feelings about past partners.

Methods

We collected a snowball sample across social media platforms (Twitter/X and YouTube). Participants were given a brief explanation of the survey and requested to re-share it. Participants gave their age, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, lifetime sexual partners, lifetime committed relationships, and lifetime casual sexual partners.

Participants also indicated if they were “red pilled,” currently in a committed relationship, if they ever had casual sex partners, as well as if they had ever experienced a break-up or had an ex. We also asked participants when they last had sex with the casual sex partner they primarily had in mind when responding to casual partner items and when the relationship ended with the person they primarily had in mind when responding to committed partner items.

Participants currently in committed relationships also indicated their current level of emotional satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and orgasm frequency.

“Alpha widow” experiences were quantified with 17 items derived from descriptions of alpha widows on the forums and blogs of red pill influencers. Given that scale items were derived from descriptions of the alpha widow phenomenon presented by red pill influencers, they should have high construct and face validity for the purposes of this study.

Participants also completed the BIDR Self-Deceptive Denial Scale (Paulhus, 1999). This scale assesses participants willingness (or unwillingness) to admit uncomfortable thoughts and beliefs.

Binary choice items were YES/NO and all scale items were assessed by participants on a 1-7 linear response scale from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.”

Items assessing the “alpha widow” phenomenon were grouped into three categories and presented below:

Comparing Past Exes to Current Partners (SC Scale)

- I have an ex or past casual sex partner who I would rather have sex with than my current romantic partner.

- I have an ex or past casual sex partner who is much more physically attractive than my current romantic partner.

- I have an ex or past casual sex partner who I would be happier with than my current romantic partner.

- My past exes or past casual sex partners make me think I could do better than my current romantic partner.

- I settled with my current romantic partner because I have an ex or past casual sex partner who would not commit.

- If I could, I would leave the relationship I am in and get back together with one of my exes.

Rumination Over Past Casual Sex Partners (C Scale)

- The most physically attractive person I have had a sexual relationship with was a casual sex partner.

- I often fantasize about one of my past casual sex partners.

- I feel as if I missed out by not having a committed relationship with one of my past casual sex partners.

- I had a casual sex partner that I wanted a relationship with, but he or she would not commit to me.

- The best sex I have had in my life was with one of my casual sex partners.

Rumination Over Past Exes (R Scale)

- I often look at the social media of one of my exes.

- I have an ex who I regret not being in a relationship with now.

- I have an ex who I consider to be “the one that got away.”

- I worry I wont find someone as good as one of my past exes.

- The “ideal man” or “ideal woman” for me is one of my exes.

- I consider one of my exes to be my “soulmate.”

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Our sample was 286 participants (31.1% female) with a mean age of 35.72 (SD 11.07). 91.3% of the sample was heterosexual, 8.4% was bisexual, and .03% was gay or lesbian. 79.4% identified as White/Caucasian, 7.3% as Other race/ethnicity, 4.9% as Hispanic, 4.5% as Black or African American, and 3.5% as Asian or Pacific Islander.

67.8% of the sample said they were not “red pilled,” 16.1% said they were “red pilled,” and 16.1% responded “Other / I don’t know what that is.”

47.2% of the sample was in a committed relationship, 69.9% of the sample had a casual sex partner in the past, and 87.4% had experienced at least one break-up in the past.

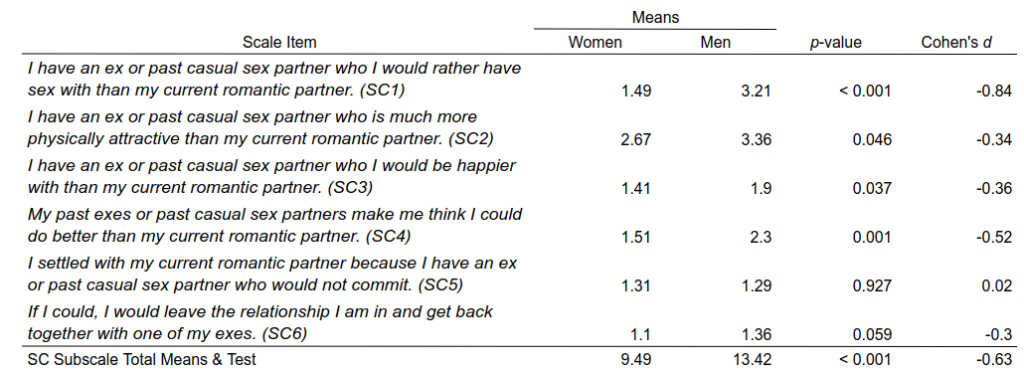

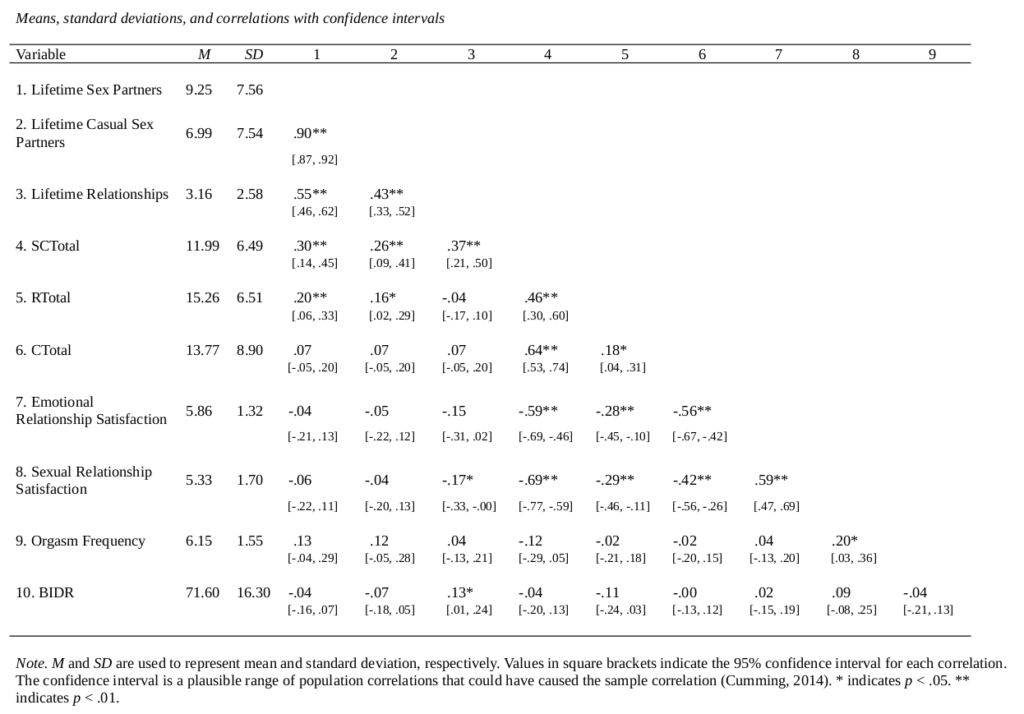

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of study variables for the sample.

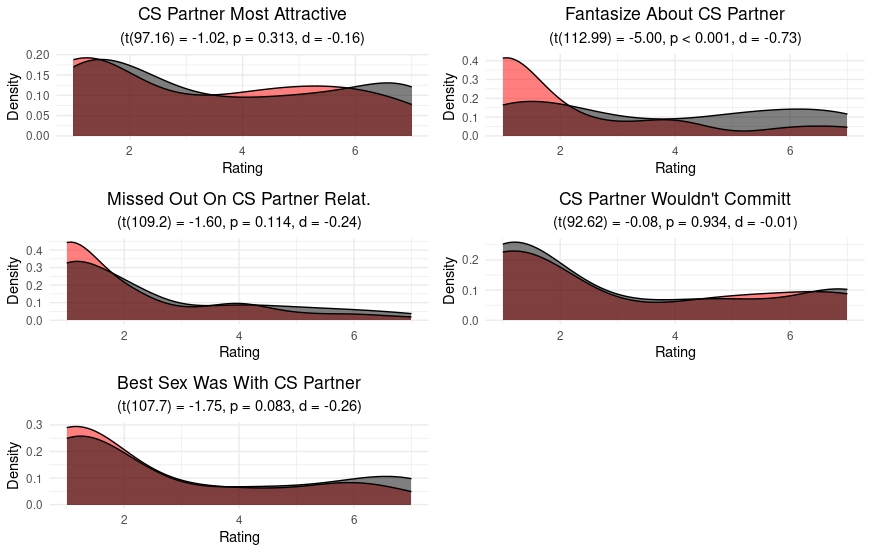

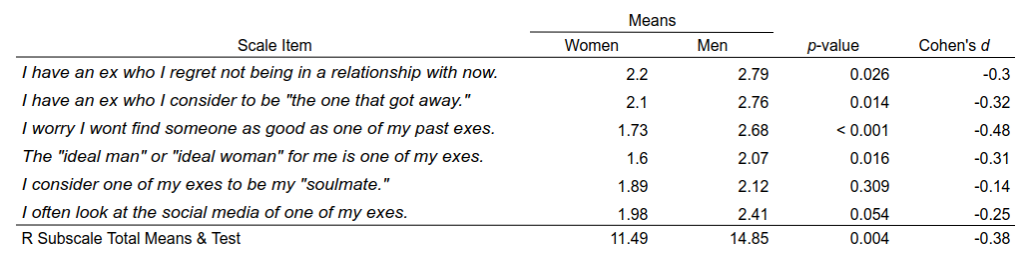

Sex Differences in Comparing Current to Past Partners (SC Scale)

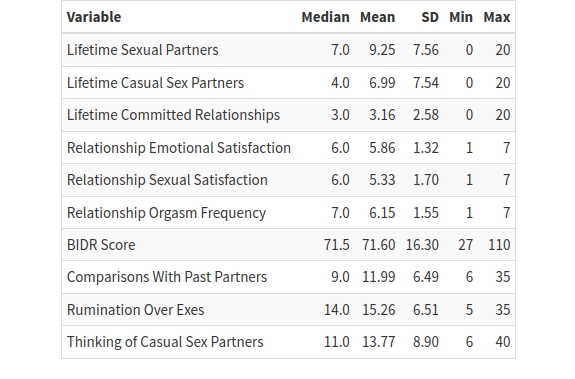

Image 1 shows density plots of sex differences with t-test results and effect sizes for each item in the subsection of the scale on comparing current partners to past partners, while Table 2 shows means and test results. Men scored significantly higher on this scale than women (t(127.91) = -3.89, p < 0.001, d = -0.63).

Overall, our results demonstrate that men are significantly more likely to compare their current partners to ex partners. The largest effects are for SC1 (preferring to have sex with an ex or past casual sex partner over one’s current relationship partner) and SC4 (having past exes or casual sex partners that make one think they “could do better”).

Results on item SC4 are especially salient to the alpha widow mythos. As red pill podcaster Rollo Tomassi wrote, “When a woman misses the opportunity to consolidate on a confirmed, high SMV (sexual market value) male that man becomes the new standard for what she believes she can attract as a potential mate.”

The current results show that this applies more to men than it does to women. Men’s exes, more than women’s exes, become a “new standard” that men compare current romantic partners to.

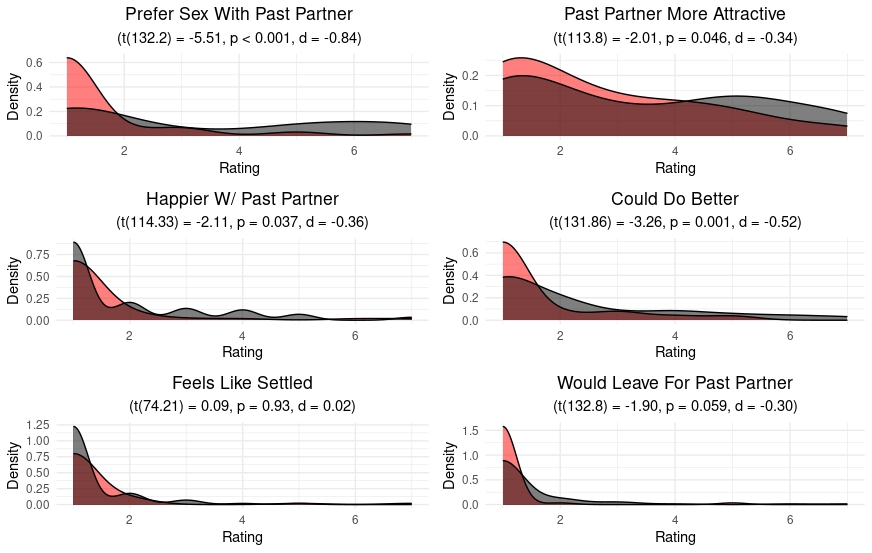

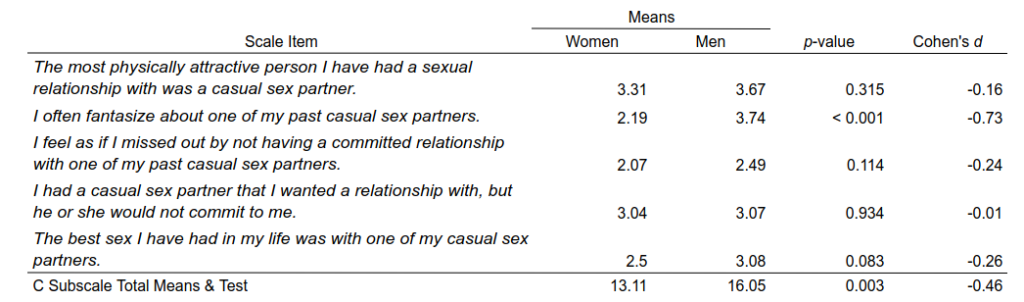

Sex Differences in Rumination Over Casual Sex Partners (C Scale)

Image 2 shows sex differences for each item in the rumination over casual sex partners subsection of the scale while Table 3 shows means and test results. Men scored significantly higher than women on this scale in total (t(101.86) = -2.99, p = 0.003, d = -0.46).

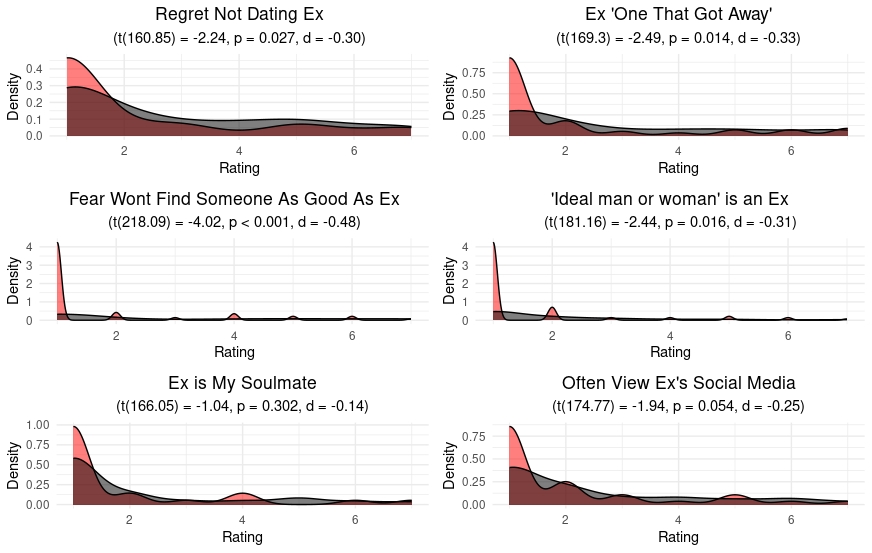

Sex Differences in Rumination Over Past Exes (R Scale)

Image 3 shows sex differences for each item in the subsection of the scale for rumination over past exes while Table 4 shows means and test results. Men scored significantly higher on this scale than women (t(172.46) = -2.95, p = 0.004, d = -0.38).

Total Sex Differences

Image 4 shows violin plots of sex differences in comparisons of current and past partners (SC Scale), rumination over past casual sex partners (C Scale), and rumination over exes (R Scale).

Correlations of Variables

Table 5 shows correlations between variables used in the current study. Participants in our study who had lower emotional and sexual satisfaction in their current relationship were more likely to ruminate over exes and compare their current partners to past partners. Participants who had more lifetime partners were also more likely to ruminate over exes and past partners, but not more likely to fantasize about past casual sex partners. Orgasm frequency in current relationships was not associated with past sexual behavior nor scale scores.

Testing for Self-Deception and Social Desirability Bias

As shown in Table 4 above, BIDR scores assessing social desirability bias and self-deception were not significantly associated with scores on our scale.

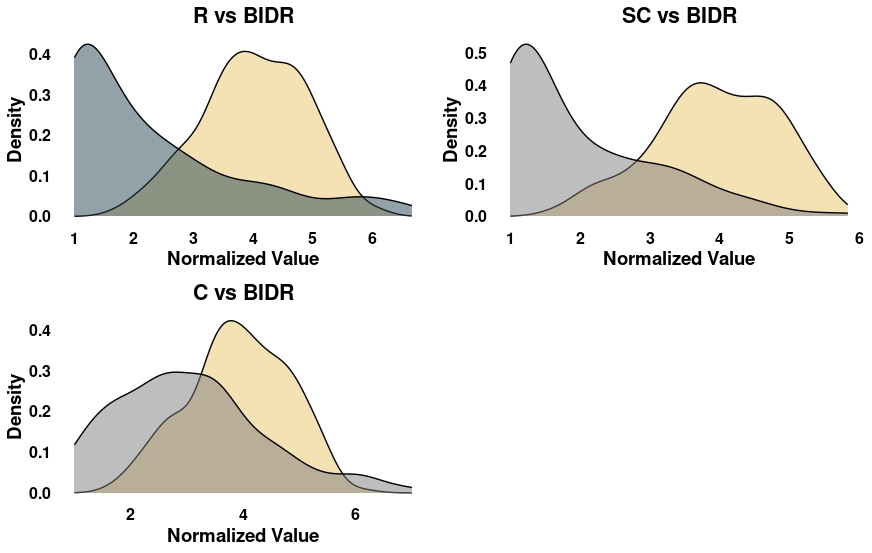

Image 5 shows normalized comparisons of BIDR scale scores with scores on our current scale assessing the “alpha widow” phenomenon. Few participants scored low (low scores are indicative of self-deception or socially desirable reporting). In other words, our participants were generally willing to admit things about themselves far worse than rumination over past partners.

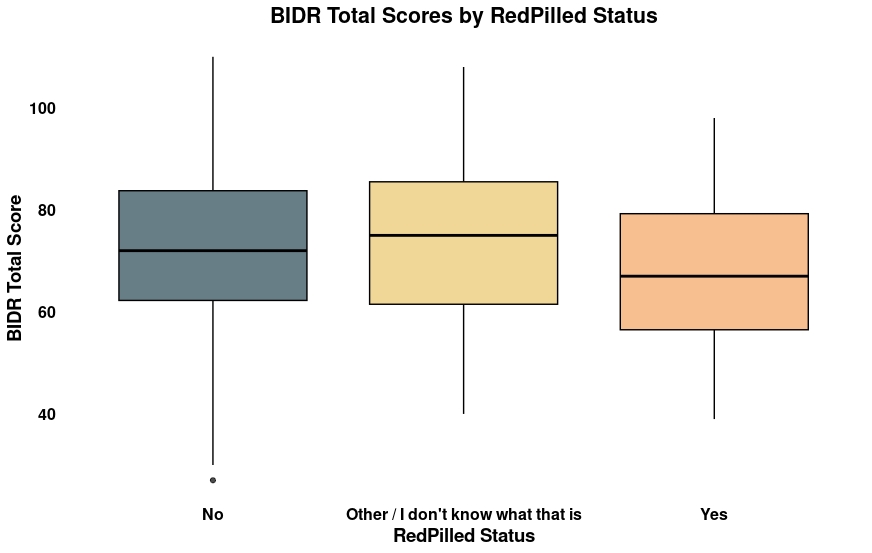

Image 6 shows a comparison of BIDR scores for participants who identified as red pilled, participants who did not, and participants who responded “Other / I don’t know what that is.”

An ANOVA was conducted to examine the effect of being red pilled on BIDR scores. The analysis revealed that there was no significant difference between groups (F(2,283) = 2.02, p = 0.13). A Tukey post-hoc test confirmed no groups were significantly different from one another (all ps > .05).

This provides further confirmation of participant reliability in a manosphere context: red pilled men believe they are more honest than others in admitting “hard truths” about themselves, but do not report differently from the rest of the sample.

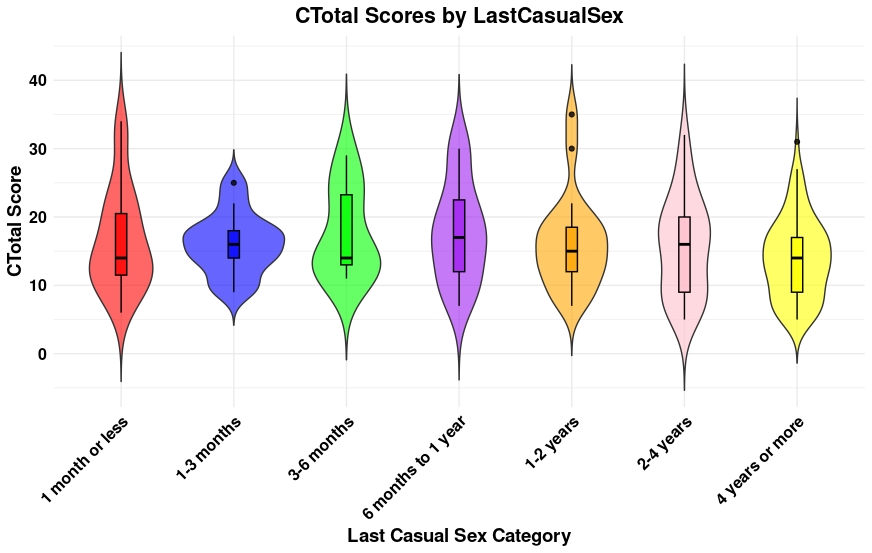

Does Rumination Attenuate With Time

We asked participants how long ago they had casual sex with the casual sex partner they had in mind when responding to questions. Image 7 shows C subscale scores by timeframe. We found no significant difference associated with recency to the last event of casual sex. This is most likely explained as a floor effect (most participants scored very low regardless of time). In other words, people forget about their past casual sex partners pretty fast.

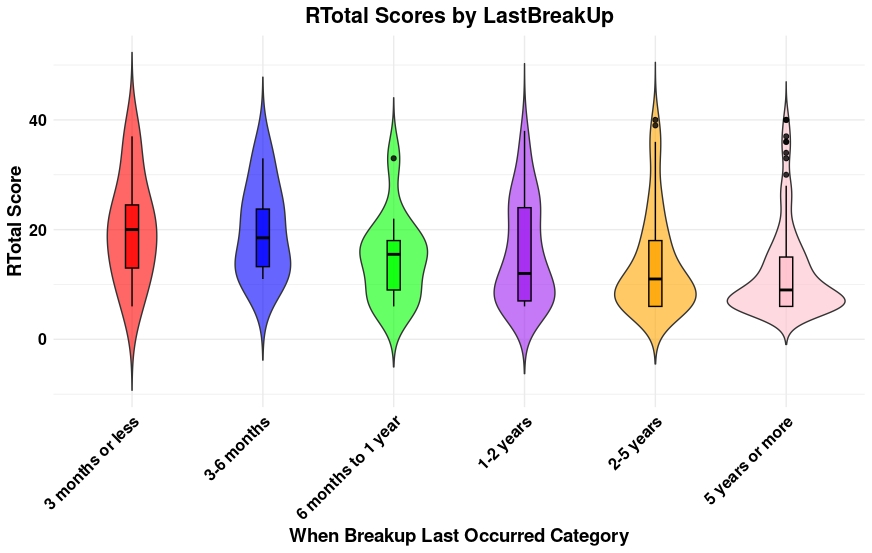

We also asked participants how long ago they experienced a break-up with the ex they primarily had in mind when responding to survey items. Here the ANOVA revealed a significant effect of time (F(5,244) = 2.49, p = 0.032) while a post-hoc test revealed no significant differences between groups (all ps > .05). Image 8 shows this result. You can see a small decline with time, but most participants started out very low even at 3 months or less.

Discussion

Few “Alpha Widows,” but More “Alpha Widowers”

In our sample, we find that the alpha widow experience is rare overall and that men score significantly higher across items on our scale. Although we have framed this using manosphere terminology, the finding that men remain more hung-up over past sexual partners is broadly consistent with past research in evolutionary psychology. Men and women experience similar amounts of emotional distress following a break-up (Morris & Reiber, 2011; Morris et al., 2015a), but men are slower to recover — and in more cases than women may also never fully recover (Morris, 2015b). Men are also more likely to engage in self-destructive behaviors following a break-up (Morris & Reiber, 2011) and express more negative emotions online following break-ups (Entwistle et al., 2021). Men fall in love faster than women do (Hill et al., 1976; Harrison & Shortall, 2011). Meanwhile, women fall out of love faster than men do, experience faster declines in relationship satisfaction, initiate more break-ups, and report more general problems in relationships than men do (Hill et al., 1976; Bühler & Orth, 2024).

Women experience more rumination than men do (Johnson & Whisman, 2013), so we may have expected women to ruminate more over past partners. However, when in love, men and women experience obsessive thoughts about their current partners to a similar extent, with around 65% of waking-hour thoughts focused on their current partners (Langeslag et al., 2012). If women fall out of love more easily and lose relationship satisfaction more quickly, we may not expect the general sex difference in rumination to carry over to rumination about past partners.

Further, we also see large sex differences at the tails of obsessive behaviors in romantic contexts. For example, 87% of stalking perpetrators are male while 78% of stalking victims are female (Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998). Men are also much more likely to use violence against romantic partners as a mate-retention strategy, such as murdering a spouse who is unfaithful or who desires to leave (Kaighobadi et al., 2009; Buss & Duntley, 2011). In other words, the most extreme expressions of failing to move on tend to be disproportionately male.

Men are often pressured to move on from break-ups quickly as a condition of masculinity. In a qualitative study of men, Hartman (2017) found men faced strong stigmas to appear tough and unphased following break-ups, despite men feeling similar emotions post-breakup. Further, losing a mate is more of a blow to male status than it is to female status. At the same time, men may lack the kind of social support that facilitates recovery following the termination of a relationship. Women report more emotional expression following a break-up than men do, as well as more willingness to seek support and lower denial over the relationship’s end (Kleinke et al., 1982). Male approaches to failed relationships more closely resemble problem-solving and strategic goals. For example, to regain confidence, men seek out new sexual partners (rebound sex) more than women do (Silber, 1996). This may create the illusion that men move on more easily, faster, and do not retain emotional “damage” or hang-ups over past romantic and sexual experiences.

The Evolutionary Reason for the Rarity of “Alpha Widows”

That few people, men or women, ruminate over exes, fantasize about past sexual partners, or pine for any significant duration over the “one that got away” is unsurprising. This could be expected from past research and evolutionary theory. Given the very low endorsement of alpha widow items, this likely also reflects the “lived experience” of the majority.

If you are reading this there is a high chance that you don’t relate to the alpha widow experience at all. You hear stories about women (or men) hung-up on exes or who are permanently “damaged” that don’t seem to apply. It’s someone else, but it isn’t you. It turns out this is how most people feel, too. This is the norm.

Human beings predominantly form serial pair bonds, or practice serial monogamy. In other words, we form long-term relationships, but they usually do not last forever. We often go from one romantic partner to another. The mating strategies of humans include break-ups, mate poaching, and infidelity. We experience strong romantic attachments, love, jealousy, and grief over loss.

As a result, we have emotional and cognitive adaptations that facilitate our navigation through this landscape. We should not expect a serially monogamous species to be permanently damaged from past romantic or sexual relationships. An inability to move on from past relationships would negatively impact future relationship formation, as well as future relationship maintenance. It would also impact seeking future relationships (especially for women, who are less oriented toward short-term mating and less likely to use future sexual encounters to get over breakups than men are).

What we should instead expect is basically what we see: strong attachments to current partners and a desire not to lose a current mate, but also an ability to move on fairly easily when a mate is inevitably lost.

Positive Illusions and Error Management Theory: Why Women Think About Exes Less

A very robust effect across research on relationships in evolutionary psychology is that of positive illusions. People consider their current partners to be more physically attractive, more desirable, and to have better personalities than third-party (or objective) raters do (Murray et al., 1996a; Barelds & Dijkstra, 2009). In our folk psychology this has been described as rose-tinted glasses. From an evolutionary perspective, this facilitates the formation and maintenance of pair bonds. Positive illusions predict how long people stay together, relationship satisfaction, and the duration of being in love (Murray et al., 1996b; Miller et al., 2006).

It is important to add that the effect of positive illusions is very strong, in some cases so much that women rate their male partners twice as attractive as objective observers rate those same men (Barelds et al., 2011). Positive illusions also cannot be dismissed as a mere “cope,” given how robustly they predict relationship outcomes. Rather, positive illusions may reflect a combination of idiosyncratic mate preferences and rose-tinted glasses. People pick who they really like (others may not share those same preferences) and really liking a partner further makes people perceive their partners as even better on top of that. Positive illusions also tend to be bidirectional; both partners see each other as better, mutually (Gordon et al., 2013).

Positive illusions can be understood in the context of Error Management Theory (EMT) (Haselton & Buss, 2000). With Sexual Strategies Theory (Buss, 1998) as a theoretical background, we should expect male and female mating psychology to be similar where mating challenges have been ancestrally similar for men and women. Long-term relationship maintenance is one area where men and women share the same adaptive challenges of keeping a mate: maintaining commitment and securing fidelity. EMT is a framework to understand how cognitive biases facilitate the fulfillment of adaptive mating strategies.

When the benefits of maintaining a relationship are higher than exiting a relationship — and this is more often the case than not from an evolutionary perspective — positive illusions (and the evolution of romantic or passionate love) facilitate preserving the relationship and are protective against relationship dissolution (Haselton & Galperin, 2013). As Haselton & Galperin (2013) wrote in a review of positive illusions in the context of EMT:

“Women are, on average, more oriented toward relationship maintenance than men are because a committed relationship was probably more strongly related to women’s reproductive success than men’s. Because of this, the error symmetry of evaluating the partner and the relationship was enhanced for women relative to men, such that it was especially costly for women to underestimate the partner’s qualities or underestimate emerging threats to the relationship.”

A meta-analysis by Fletcher and Kerr (2010) supported this observation: women had stronger positive illusions than men in respect to partner traits — and stronger negative illusions when assessing relationship interactions. For example, women might overestimate a partner’s attractiveness, but also underestimate the extent to which a partner did not forgive them after a fight. Consistent with EMT, women’s cognitive biases were more attuned to relationship preservation than those of men.

Our results are consistent with this. Perhaps one of the worst signs for a relationship is having one’s mind on a rival mate. We should expect the sex that has a higher orientation toward commitment and investment to have their mind elsewhere less, which is what we see in our current results. Men ruminate about past partners more, miss past partners more, and fantasize about their past casual sex partners more.

Once again, evolutionary psychology has revealed what looks more like a black pill for women than it does for men.

Large Sex Differences in “Alpha Widow” Experiences in the Context of Evolutionary Psychology

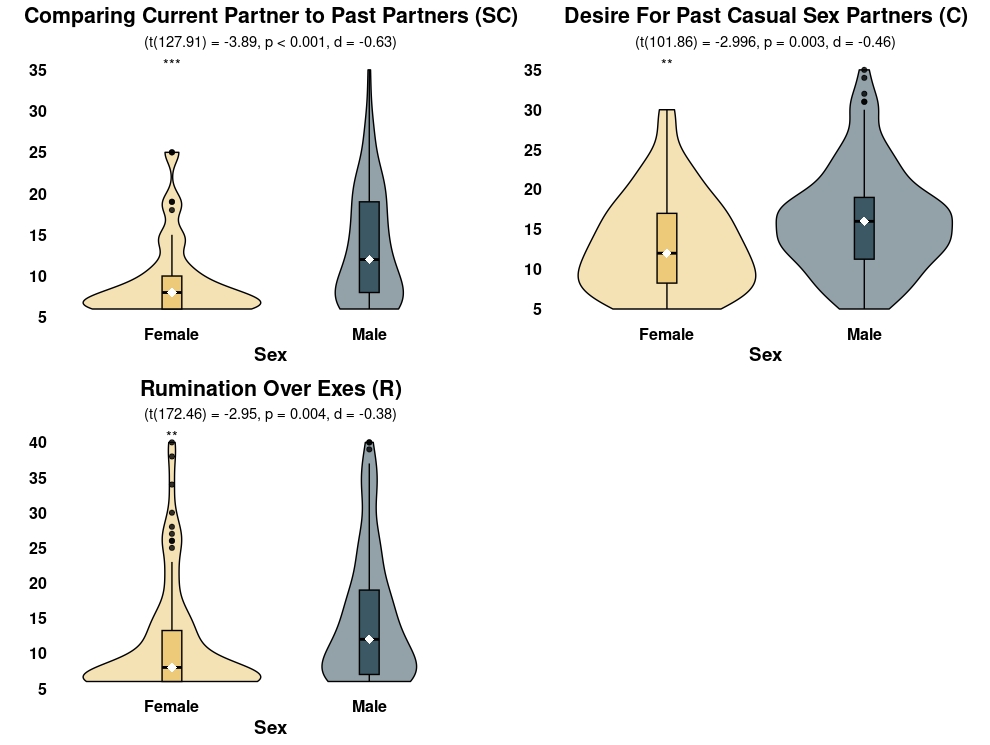

A few of our items produced especially large sex differences, consistent with Sexual Strategies Theory (Buss, 1998). Men are expected to value sexual encounters more, to desire more sexual novelty, to be less sexually faithful, and to also regret missed sexual experiences more.

Scale items that asked about sexual desire or sexual behavior showed a large sex difference (d = -0.79) but were small (and did not reach statistical significance) for items on emotional rumination (d = -0.32). Remember, we expect male and female mating psychology to be more similar where male and female challenges are similar (long-term relationship formation) and less similar where challenges are different (casual sexual behavior).

Accounting for Social Desirability and Self-Deception

Our measure of social desirability and self-deception was a selection of 18 items from the BIDR Self-Deceptive Denial Scale (Paulhus, 1999). These items were excluded from the full BIDR in part because they were seen as “too offensive” by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). In other words, these were questions that mainstream academia literally does not allow you to ask. They represent the types of questions participants are most likely to lie about and most likely to deceive themselves about, such as harming friends, enjoying being cruel, enjoying seeing people get killed, sexual fantasies, and having a desire to commit murder or rape.

Our results show a remarkable level of honesty in respect to these questions. Scores on our selection of BIDR items were also much higher than scores on our scale assessing rumination over past partners, desire for past casual sex partners, and comparing current partners to past partners.

A popular cope that we have encountered in the wild when research results do not confirm manosphere myths is that everyone is simply lying.

For that to be true in this case, you would essentially need to believe that our questions in respect to past partners and exes are among the most controversial in the world — even more controversial than admitting a desire to murder, rape, get revenge, and bully others.

A more plausible interpretation is that if participants are willing to admit and acknowledge the dark side of their own psychology across these domains, they probably won’t hesitate to admit that they are still hung-up on an ex. A supermajority of the sample are not lying to themselves and researchers (only about these items — while being quite willing to admit everything else), rather, participants simply don’t ruminate and fantasize about past partners very much.

We also found no correlations between our scale items and BIDR scores. If an effect of social desirability or self-deception were at play we would expect to see a positive correlation, whereby individuals who scored lower on the BIDR also scored lower across our scale items.

Finally, we found no association between being red pilled and BIDR scores. If red pilled men perceive themselves as honest they must also concede that everyone else is being just as honest as they are.

Motivations To Believe In “Alpha Widows”

The top motivation for men to enter the manosphere, or red pill, spaces is having experienced a recent break-up. We also know that some people do not recover from break-ups and that men are less likely to recover than women. The alpha widow narrative may simply be a form of projection. Men who are struggling to recover, which is normal in the immediate aftermath of a break-up, may believe that others will share their experience and that it will never end. Perhaps unaware that men actually do a little worse with break-ups and ruptured emotional attachments, men may incorrectly assume that what hurt them, or that what has left a lasting impression upon themselves, would affect women even more.

Most people also know of someone who has been hung-up on a past partner. A lot of people confuse these kinds of third-hand stories for “lived experience,” alongside hearing countless anecdotes from the Internet. This is one mechanism through which inaccurate estimates of base rates are formed. If you participate in a community that talks about alpha widows then you are going to hear a lot of stories about alpha widows. It will simply seem more common than the norm: women moving on and forgetting about their exes.

The alpha widow narrative is also one among many in the manosphere that serves as an ego-fulfilling revenge fantasy. It is not a fun experience to ruminate over past partners or have unfulfilled relationship desires (e.g. regretting that a casual sex partner did not desire a committed relationship with you). Men who are angry with women may tell stories of women’s suffering because it feels good to them. Further, men who have experienced rejection may tell stories of women experiencing similar rejections. Men may wish to believe in a sort of karmic punishment, or that women will experience what they once did, be it rejection or suffering the loss of a mate.

Further, even before the manosphere, telling oneself, “I am the one who got away” has been a strategy that individuals use following a break-up to help themselves emotionally cope. The alpha widow story can also be a way to cope with one’s own failed relationships. A Google search for the phrase, “I alpha widowed her” turns up numerous entries on manosphere forums where men reframe their own break-ups in this way. The belief that you had a lasting impact on a woman, that you were the “best” of all her relationship experiences, and that she continues to think about you is soothing to the ego in a way that, “she does not think about me, she has moved on, she is having sex with someone else, and she thinks that the sex is better with her new partner” is not.

Conclusion

We find robust sex differences that demonstrate men ruminate over exes, fantasize about past casual sex partners, and compare their current romantic partners with past partners more than women do. Importantly, in both men and women, strong fixations on past partners is rare. Finally, our results cannot be attributed to self-deception nor social desirability bias.

References

Barelds, D. P., & Dijkstra, P. (2009). Positive illusions about a partner’s physical attractiveness and relationship quality. Personal Relationships, 16(2), 263-283.

Barelds, D. P., Dijkstra, P., Koudenburg, N., & Swami, V. (2011). An assessment of positive illusions of the physical attractiveness of romantic partners. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28(5), 706-719.

Bühler, J. L., & Orth, U. (2024). How relationship satisfaction changes within and across romantic relationships: Evidence from a large longitudinal study. Journal of personality and social psychology.

Buss, D. M. (1998). Sexual strategies theory: Historical origins and current status. Journal of Sex Research, 35(1), 19-31.

Buss, D. M., & Duntley, J. D. (2011). The evolution of intimate partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16(5), 411-419.

Entwistle, C., Horn, A. B., Meier, T., & Boyd, R. L. (2021). Dirty laundry: The nature and substance of seeking relationship help from strangers online. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(12), 3472-3496.

Fletcher, G. J., & Kerr, P. S. (2010). Through the eyes of love: reality and illusion in intimate relationships. Psychological bulletin, 136(4), 627.

Gordon, E. A., Johnson, K., Heimberg, R. G., Montesi, J. L., & Fauber, R. L. (2013). Bi-directional positive illusions in romantic relationships: Possibilities and pitfalls for the socially anxious. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32(2), 200-224.

Haselton, M. G., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Error management theory: a new perspective on biases in cross-sex mind reading. Journal of personality and social psychology, 78(1), 81.

Haselton, M. G., & Galperin, A. (2013). Error management in relationships. Handbook of close relationships, 234-254.

Harrison, M. A., & Shortall, J. C. (2011). Women and men in love: Who really feels it and says it first?. The Journal of social psychology, 151(6), 727-736.

Hartman, T. (2017). Men, masculinity, and breakups: Resisting the tyranny of “moving on”. Personal Relationships, 24(4), 953-969.

Hill, C. T., Rubin, Z., & Peplau, L. A. (1976). Breakups before marriage: The end of 103 affairs. Journal of social issues, 32(1), 147-168.

Johnson, D. P., & Whisman, M. A. (2013). Gender differences in rumination: A meta-analysis. Personality and individual differences, 55(4), 367-374.

Kaighobadi, F., Shackelford, T. K., & Goetz, A. T. (2009). From mate retention to murder: Evolutionary psychological perspectives on men’s partner-directed violence. Review of General Psychology, 13(4), 327-334.

Kleinke, C.L., Staneski, RA, & Mason, J.K. (1982). Sex differences in coping with depression. Sex Roles, 8, 877-889.

Langeslag, S. J., Van der Veen, F. M., & Fekkes, D. (2012). Blood levels of serotonin are differentially affected by romantic love in men and women. Journal of Psychophysiology.

Miller, P. J., Niehuis, S., & Huston, T. L. (2006). Positive illusions in marital relationships: A 13-year longitudinal study. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(12), 1579-1594.

Morris, C. E., & Reiber, C. (2011). Frequency, intensity and expression of post-relationship grief. EvoS Journal: The Journal of the Evolutionary Studies Consortium, 3(1), 1-11.

Morris, C. E., Reiber, C., & Roman, E. (2015). Quantitative sex differences in response to the dissolution of a romantic relationship. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 9(4), 270.

Morris, C. E. (2015). The Breakup Project: using evolutionary theory to predict and interpret responses to romantic relationship dissolution. State University of New York at Binghamton.

Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Griffin, D. W. (1996). The benefits of positive illusions: Idealization and the construction of satisfaction in close relationships. Journal of personality and social psychology, 70(1), 79.

Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Griffin, D. W. (1996). The self-fulfilling nature of positive illusions in romantic relationships: love is not blind, but prescient. Journal of personality and social psychology, 71(6), 1155.

Paulus (1999). https://www2.psych.ubc.ca/~dpaulhus/research/SDR/downloads/MEASURES/SDD.htm

Reeve, S. D., Kelly, K. M., & Welling, L. L. (2017). The effect of mate value feedback on women’s mating aspirations and mate preference. Personality and Individual Differences, 115, 77-82.

Silber, S. E. (1996). How men and women cope with the breakup of a long-term, romantic, non-marital relationship (Master’s thesis, California State University, Northridge).

Tjaden, P. G., & Thoennes, N. (1998). Stalking in America: Findings from the national violence against women survey. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice.

6 comments

This is an interesting post that makes a lot of persuasive points. One statement struck me as odd, though: “Further, losing a mate is more of a blow to male status than it is to female status.” What is the definition of “status” here, and what is the evidence supporting a gender difference? Anecdotally, I don’t see men losing a lot of “status” with respect to, say, business or friendships when a marriage or long-term relationship ends. Especially with older couples, I perceive women losing more status than men. Of course, if there’s good data to the contrary that would be more persuasive.

Keep up the good work!

the unknowns cited and author’s bias (agenda) are pretty explicit

Following up on the above comment: A quick literature check suggests that women lose more “status” than men after a divorce: “Divorce is associated with significant socioeconomic changes, especially for women, and the impact may be especially severe for minority women who are in a vulnerable financial position before the end of marriage. Relative SES disruptions and associated disruption in social standing or status”

Divorce, health, and socioeconomic status: An agenda for psychological science. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/current-opinion-in-psychology

The reverse (“alpha widower”) happened for me as well as several others I know. For men who were PUAs in their youth, they were cultivating and practicing charisma extensively with a full time job level of commitment. Later they decided to get more serious about their career and didn’t have as much time available, and so naturally couldn’t attract women as beautiful as they were able to before. Some end up settling for a woman they get along with but aren’t all that attracted to (and quickly get to a dead bedroom), others go celibate and move on with their life, but there is naturally a period of mental turbulence at having to accept that your mate value isn’t as high as when you focused all of your mental effort towards it.

This is very interesting, however something isn’t sitting right with me. In the beginning of the study you noted that “women fall out of love faster than men do, experience faster declines in relationship satisfaction, initiate more break-ups, and report more general problems in relationships than men do.” At the end of the study you noted that “Women are, on average, more oriented toward relationship maintenance than men are.” How can these both be true? That seems contradictory, and the flipside seems contradictory too. How is it that men fall in love faster but experience weaker positive illusions? I’m having trouble making sense out of this.

I’m not sure that this disproves “Alpha Widows” so much as it proves that there are also “Alpha Widowers”.

Was that ever up for debate? I don’t know much about this concept, but it seems unlikely to me that there were people claiming that this was something that only affects one gender. Maybe I’m just not hanging out on the right sites to see that sort of thing.