Many surveys have been conducted on what careers the opposite sex find attractive. These are easy to look up and often include large lists of careers. Attractive careers usually end up being what you would expect. They tend to be exciting (think “surf instructor”) or uniformed (“doctor” or “fireman”). Incidentally, the most attractive careers are not necessarily the highest paying careers. For example, the job-search website Zippia found the average salary of the top 25 most attractive careers to be $74,154.

According to Forbes, 24% of the total U.S. workforce is in a STEM field. Statistics from the US. The Department of Labor indicates 37.4 million Americans work in the trades, which would constitute approximately 13% of American labor. These categories contain many jobs you might not think of as technology or trades careers, so perhaps the real numbers are smaller. Nonetheless, tech and trades constitute a much larger number of regular American workers than sexy careers like airline pilot or Brazilian jiu-itsu instructor.

Technology and trades careers are also at opposite ends of the career spectrum in many ways. Contrary to popular memes depicting the trades as easy money, trade careers are still among the lowest paying careers, while technology careers are among the highest. The stereotypes that come to mind when you imagine a computer programmer and a brick mason probably look very different. Keeping in mind that stereotype accuracy is one of the most well-replicated effects in psychology, you may not be surprised to learn that some truth exists in the mental image that you conjure up.

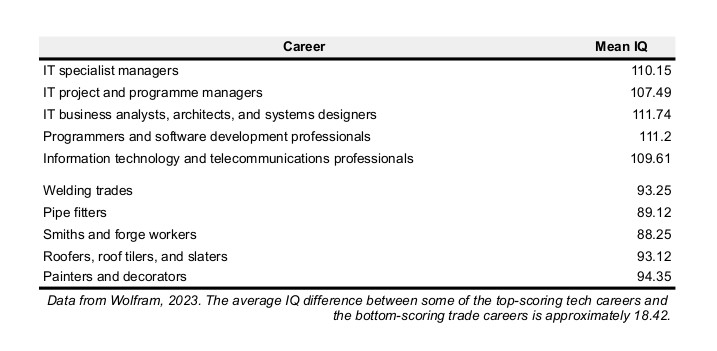

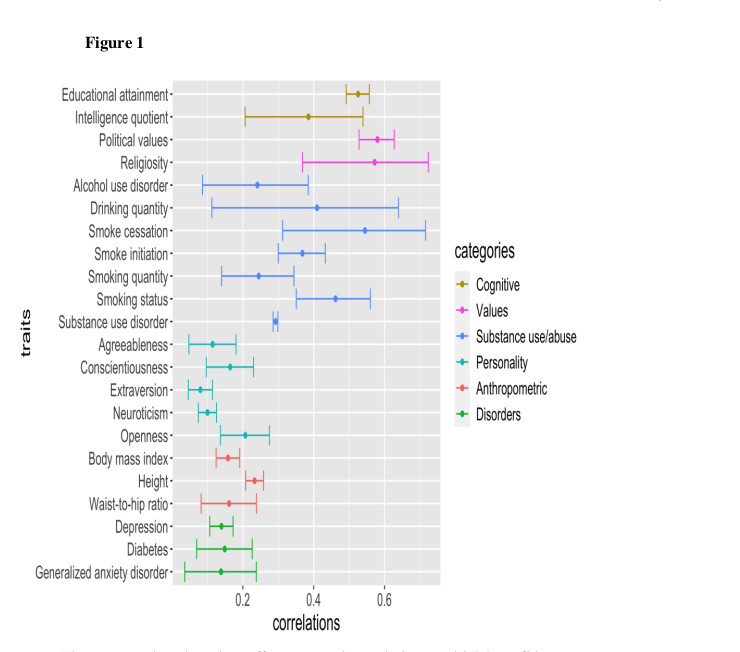

There are meaningful and often large differences in educational attainment, personality, and intelligence between tech and trade careers (Wolfram, 2023; Anni et al., 2024). The lifestyles of tech employees and tradesmen are different; the work that they do is different. Different types of people self-select into different careers based on their traits. The jobs that they do further shape their personalities. They learn different skills. Their bodies change in different ways, from sedentarism or overexertion. They build the information highways or the roads that you drive on.

The search for the “most attractive” career, face, or whatever else ultimately ends up being a comparison of means. However, attraction and mate selection is not random. People really do have “types” and individuals really do prefer different things from one another. This is why we see assortative mating for political ideology, educational level, occupation, personality traits, and everything else. This is important to understand about attraction: preferences vary by individual. Different kinds of women pick different kinds of men, and vice versa. Different kinds of women will prefer men with technology jobs or trade jobs.

Keep this in mind as we go forward and compare some tech and trade careers. Individual outcomes are not the same as group means. If the average IQ of pipe fitters is 89.12, this does not mean every pipe fitter has an IQ of 89.12. There are, without a doubt, highly intelligent pipe fitters out there. (Perhaps they often feel like they are surrounded by idiots!) If the average short-term attractiveness of web developers is a 3.6 on a scale of 7, this does not mean some women did not find them to be a 6. Further, the results of this survey will be shaped by the sample characteristics due to the role of preference in assortative mating.

Methodology

Survey Items

Participants reported their age, sex, sexual orientation, political ideology, and highest level of educational attainment. Participants also indicated if they were in a trade or technology career, as well as if their current romantic partner was in a trade or technology career.

For this study, female participants were instructed to report what they found attractive. Male participants were instructed to report what they think women find attractive. In other words, we are looking at what women find attractive and what men think women find attractive. For example, on one item to assess preferences for conventional masculinity, women were asked to indicate agreement with the statement, “I like conventional masculinity in a male partner,” while men were asked to indicate agreement with the statement, “Women like conventional masculinity in a male partner.” On the item for long-term desirability, women were asked to rate male career attractiveness with the statement, “How attractive is an electrician as a long-term mate to you,” while men were asked, “How attractive is an electrician as a long-term mate to women.”

Three items were used to assess preferences for conventional masculinity:

- “I [or women] like conventional masculinity in a male partner.”

- “I [or women] like traditional gender roles in my [their] relationship.”

- “I [or women] want my [their] male romantic partner to be physically strong.”

Nine technology and nine skilled trades careers were rated by participants for long-term attractiveness, short-term attractiveness, and masculinity. Two-sentence descriptions of technology and trades careers were provided before the ratings.

- Trade careers: electrician, plumber, carpenter, welder, mason, mechanic, painter, heavy equipment operator, and roofer.

- Technology careers: web developer, programmer, systems analyst, cybersecurity architect, cloud administrator, database developer, application developer, IT auditor, and tech support analyst.

Technology and trade career ratings were summed for total scores of long-term attractiveness, short-term attractiveness, and masculinity. Two additional questions were asked:

- Overall, how attractive do you find skilled trades as a career for a potential romantic partner?

- Overall, how attractive do you find technology careers for a potential romantic partner?

Participants were also asked to submit qualitative descriptions of what they found attractive and unattractive about technology and trade careers for men.

Results

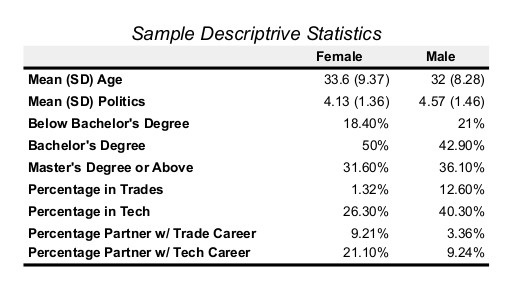

Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

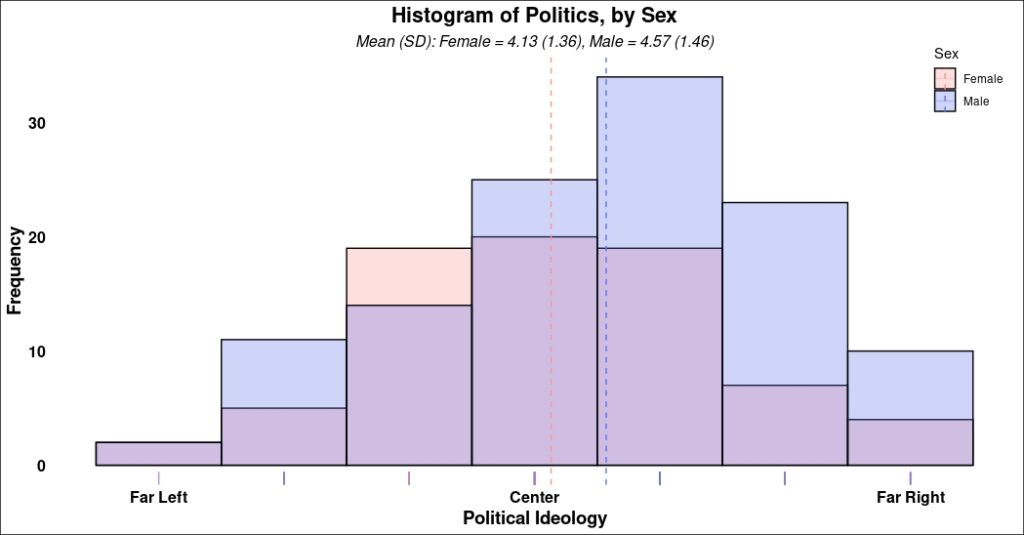

This is pretty typical of the samples that I collect (mostly DatePsychology readers): largely centrist in politics, highly educated relative to the general population, and diverse in age. Tech careers are overrepresented relative to the general population, which is important to keep in mind when we look at career attractiveness ratings. We should expect some bias toward tech.

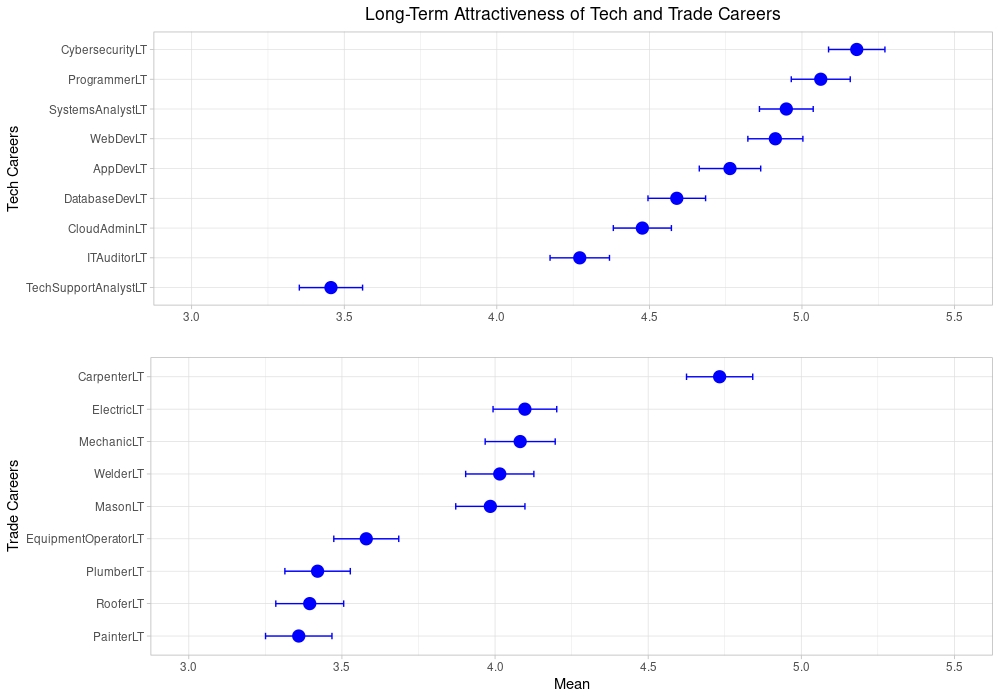

Long-Term Attractiveness Ratings of Technology and Trade Careers

Technology careers (M = 41.66) were rated higher than trade careers (M = 34.67) in long-term attractiveness, (t(380.55) = 6.63, p < .001, 95% CI [4.92, 9.07]). Cybersecurity architect was the highest for technology careers, while carpenter was the highest for trade careers. Tech support analyst stands out as ranking particularly low for technology careers.

For the trades, maybe carpenter seemed like a better trade due to associations with woodworking and craftsmanship. Plumbers and electricians are two trades that require licensing and represent the most highly paid trades on the list, yet plumber also received low ratings. Plumber may just not seem like a very “sexy” job. Roofers and painters, also rated low, may be perceived as less prestigious or less skilled. Ultimately we can only speculate, but those are my guesses.

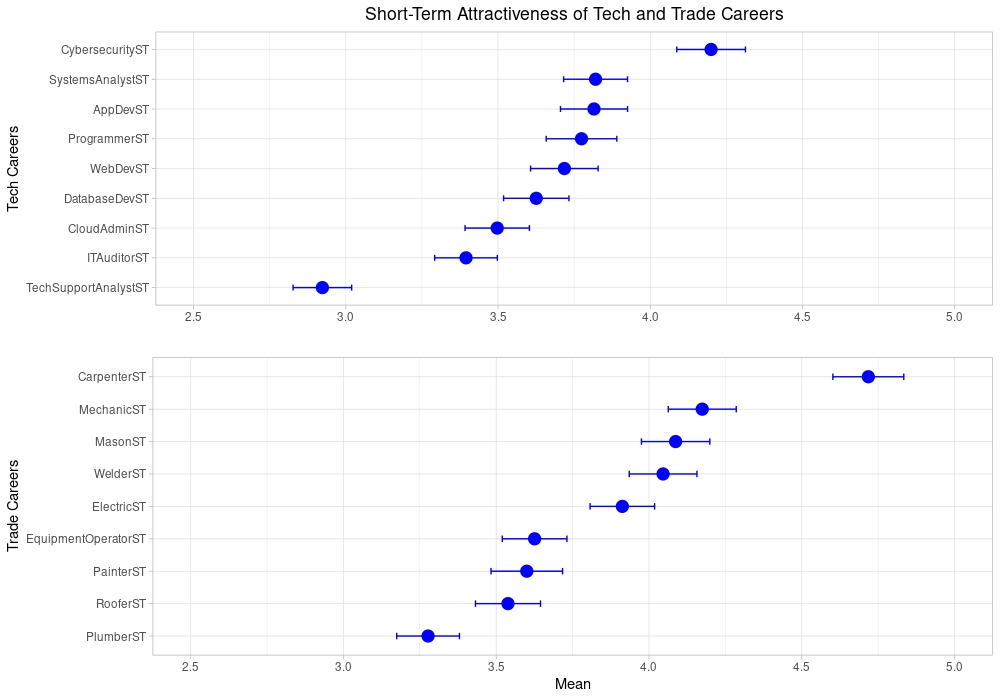

Short-Term Attractiveness Ratings of Technology and Trade Careers

Technology careers total scores (M = 32.77) were rated lower than trade careers (M = 34.98), but this difference was not statistically significant (t(387.55) = -1.89, p = .059, 95% CI [-4.51, 0.09]). Some careers clearly outranked others, however. For example, a mechanic was a “sexier” career than most technology careers. What technology careers signaled in long-term attractiveness, they did not signal in short-term attractiveness to the same extent. You might hire a Chippendales “sexy construction worker” for your bachelorette party, but you’re less likely to find a “sexy cloud administrator.”

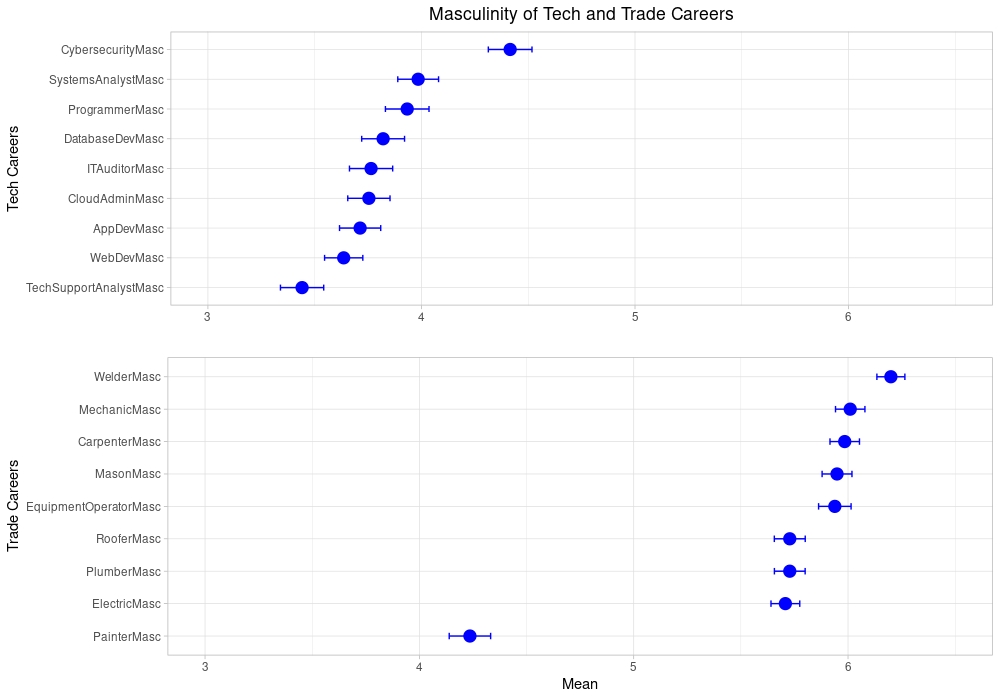

Masculinity Ratings of Technology and Trade Careers

Here we see large differences in masculinity ratings for technology (M = 34.46) and trade careers (M = 51.48) (t(323.38) = -18.81, p < .001, 95% CI [-18.80, -15.24]). Probably unsurprising, because this is consistent with our stereotypes. Painters got rated much lower, perhaps because it is seen as a less physically demanding career.

Sex Differences in Attractiveness and Masculinity Ratings

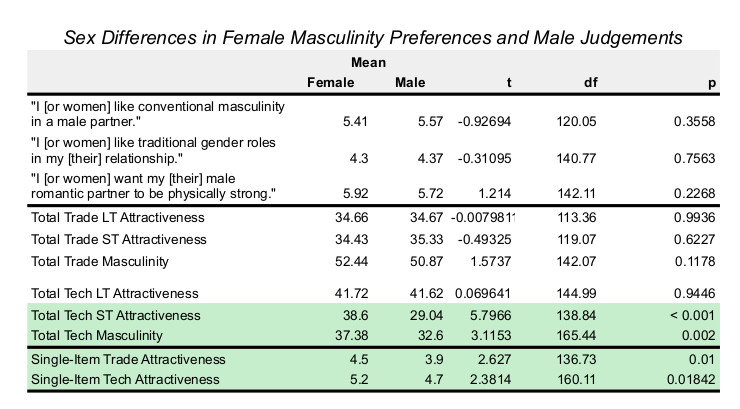

Image 6 shows sex differences for the three masculinity items, muscularity, and attractiveness ratings. Men were accurate at predicting female ratings for masculinity items and trade careers, but underestimated short-term attractiveness and masculinity ratings given by women for technology careers. Men also under-rated the single-item overall attractiveness scores of both technology and trade careers.

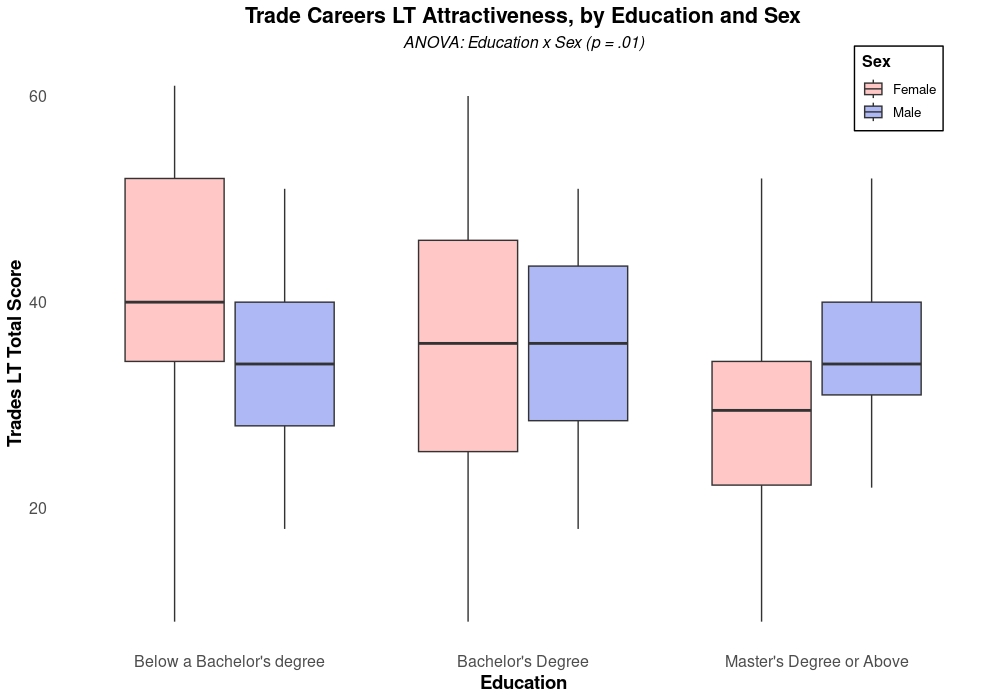

Two-Way ANOVAs of Sex and Education: Trade Career Long-Term Attractiveness

A two-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between education and sex on trade career long-term attractiveness, (F(2, 189) = 4.69, p = .01). Post-hoc comparisons showed that women with an educational level below a bachelor’s degree rated trade careers as significantly more attractive than women with a master’s degree or above (p = .02). No other contrasts were significant.

Two-Way ANOVAs of Sex and Education: Trade Career Short-Term Attractiveness

A two-way ANOVA revealed no significant main effects of education, (F(2, 189) = 2.05, p = .13), or sex, (F(1, 189) = 0.40, p = .53), on the short-term attractiveness of trade careers. The interaction between education and sex was also not significant, (F(2, 189) = 2.59, p = .08).

Two-Way ANOVAs of Sex and Education: Trade Career Masculinity

For masculinity ratings of trade careers, there were no significant main effects of education, (F(2, 189) = 0.59, p = .56) or sex, (F(1, 189) = 2.72, p = .10), nor was there an interaction (F(2, 189) = 0.28, p = .75).

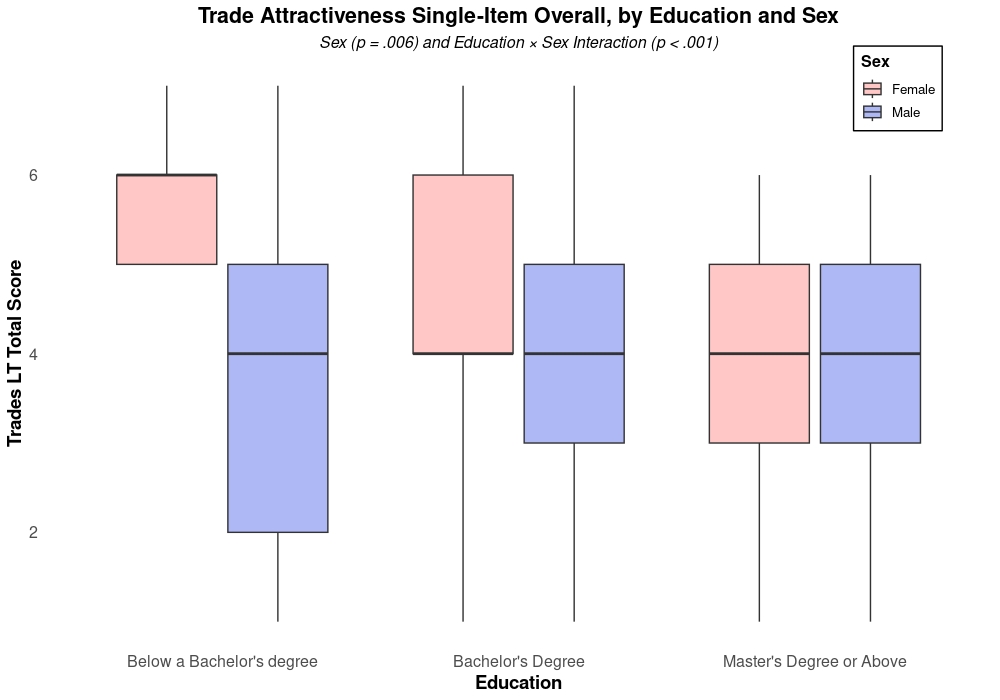

Two-Way ANOVAs of Sex and Education: Single-Item Trade Overall Attractiveness

Here a two-way ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of education on the perceived overall attractiveness of trade careers, (F(2, 189) = 0.60, p = .55). However, there was a significant main effect of sex, (F(1, 189) = 7.82, p = .006), and a significant interaction between education and sex, (F(2, 189) = 7.88, p < .001).

Two-Way ANOVAs of Sex and Education: Technology Career Long-Term Attractiveness

A two-way ANOVA on the long-term attractiveness of tech careers revealed no significant main effect of education, (F(2, 189) = 2.10, p = .126), no significant main effect of sex, (F(1, 189) = 0.04, p = .851), and no significant interaction between education and sex, (F(2, 189) = 0.40, p = .673).

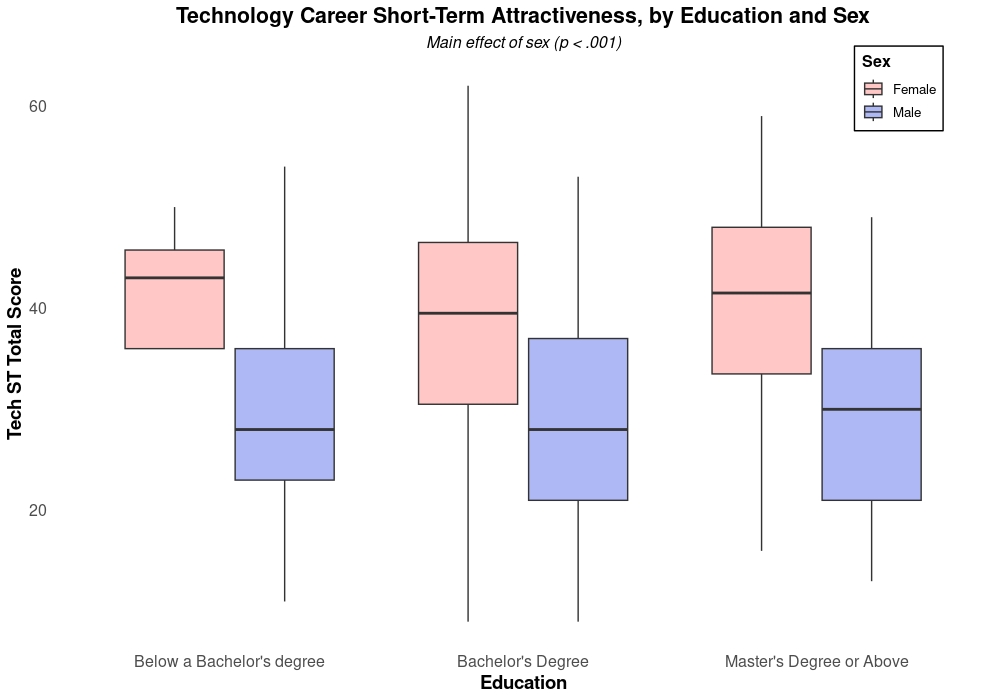

Two-Way ANOVAs of Sex and Education: Trade Career Short-Term Attractiveness

For the short-term attractiveness of technology careers, there was no significant main effect of education, (F(2, 189) = 0.06, p = .944), but a significant main effect of sex, (F(1, 189) = 36.17, p < .001). The interaction between sex and education was not significant, (F(2, 189) = 0.11, p = .895).

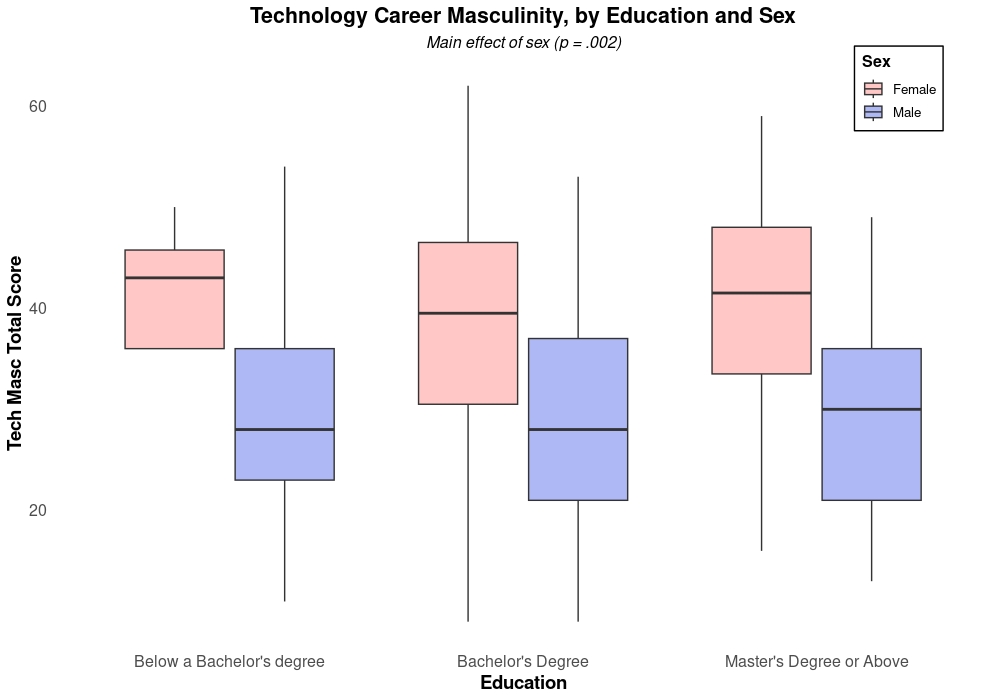

Two-Way ANOVAs of Sex and Education: Trade Career Masculinity

Perceived masculinity of tech careers revealed no significant main effect of education, (F(2, 189) = 0.20, p = .818), but a significant main effect of sex, (F(1, 189) = 9.67, p = .002). There was no significant interaction between education and sex, (F(2, 189) = 0.46, p = .632).

Two-Way ANOVAs of Sex and Education: Single-Item Technology Overall Attractiveness

For single-item overall attractiveness of technology careers, a main effect was found for sex (F(1, 189) = 6.36, p = .013), but not for education (F(2, 189) = 2.05, p = .132) nor the sex and education interaction (F(2, 189) = 0.43, p = .650).

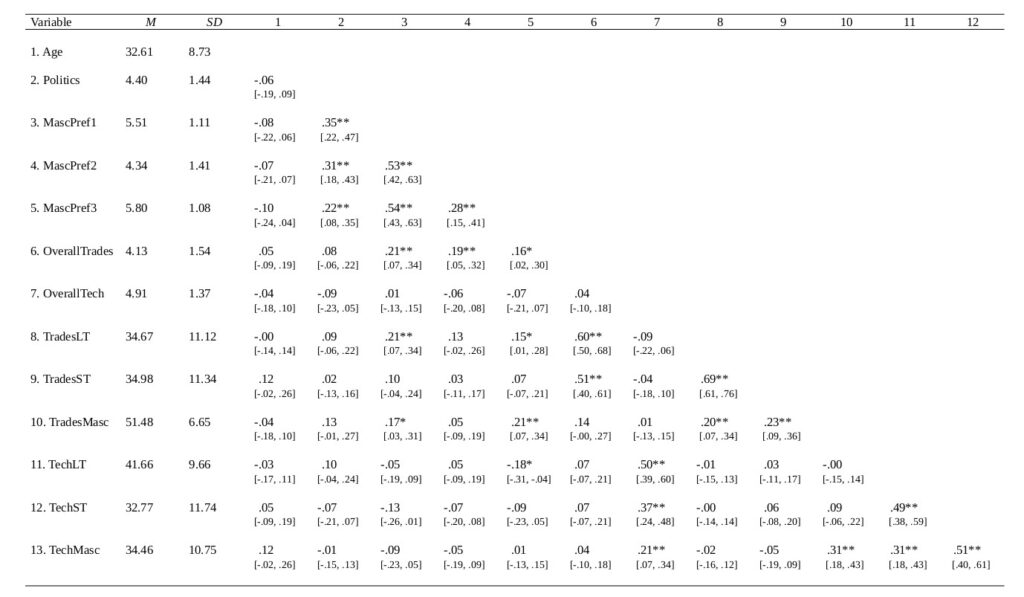

Correlation Matrix of Variables

Participant political ideology was associated with all three masculinity items (rs = .22 to .35), such that right-leaning individuals scored higher in endorsement of conventional masculinity as ideal in a male partner. Neither political ideology nor age were associated with any career attractiveness variables.

Masculinity preferences were intercorrelated (preferences for conventional masculinity, traditional gender roles, and physical strength in a male partner) (rs = .28 to .54).

Participants who endorsed more conventional masculinity in a male partner rated trade careers higher in overall attractiveness (.21), trade careers more desirable in a long-term partner (.21), and trades as more masculine (.17). Higher endorsement of traditional gender roles was associated with ratings trades as more desirable overall (.19), but was associated with no other career variables. Higher endorsement of muscularity in a male partner was associated with rating trades as more desirable overall (.16), trades as more desirable in a long-term partner (.15), trades as more masculine (.21), and technology careers as less desirable in a long-term partner (-.18).

Ratings of long-term attractiveness, short-term attractiveness, and masculinity were intercorrelated for careers. Participants who rated trade careers as more desirable in the long term also rated trade careers as more desirable in the short term and more masculine. Similarly, participants who rated technology careers as more desirable in the long term also rated technology careers higher in short-term desirability and masculinity.

Participant Employment and Attractiveness Ratings

Comparing participants who were in trade careers with participants who were not across all variables, differences only emerged for assessments of short-term attractiveness. Participants who were in the trades rated technology careers as significantly lower (M = 28.25 in short-term attractiveness than participants who were not in the trades (M = 35.02) (t(19.13) = 2.66, p = .015, 95% CI [1.48, 12.31]).

Participants in technology careers rated the single-item overall attractiveness of technology careers significantly higher (M = 5.37) compared to those not in technology careers (M = 4.66), (t(158.78) = -3.71, p < .001, 95% CI [-1.08, -0.33]). All other comparisons were nonsignificant (ps > .05).

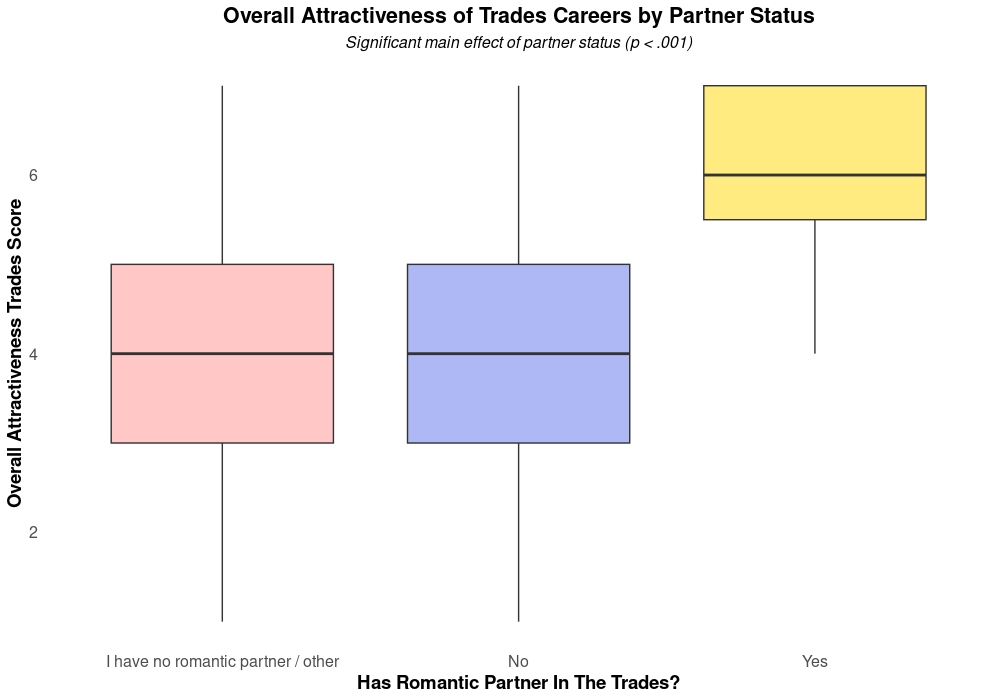

Participant Partner Employment in Trades and Attractiveness Ratings

For masculinity preferences, only a significant main effect of having a partner in the trades was observed for a preference for muscularity, (F(2, 192) = 3.87, p = .022). Post hoc comparisons revealed that participants who indicated they did not have a partner in the trades (M = 6.00) endorsed a greater preference for muscularity than single participants (M = 5.61) (p = .036).

For long-term trade attractiveness, there was a significant main effect (F(2, 192) = 6.23, p = .002) Participants who indicated that they had a romantic partner in a trade career had significantly higher long-term trade attractiveness scores (M = 45.5) compared to single participants (M = 34.6), (p = .005), and participants who did not have a romantic partner in the trades (M = 33.3) (p = .002). No other pairwise comparisons were significant (all ps > .05).

For single-item overall attractiveness of trade careers, a significant main effect was observed (F(2, 192) = 9.41, p < .001). Participants who had a romantic partner in the trades rated trades as significantly higher in overall attractiveness (M = 6.00) than single participants (M = 4.01) (p < .001) and participants who did not have a partner in the trades (M = 4.03) (p < .001). No other comparisons were significant (all ps > .05).

All other analyses, including those for trade short-term attractiveness and trade masculinity, yielded nonsignificant results (all ps > .05).

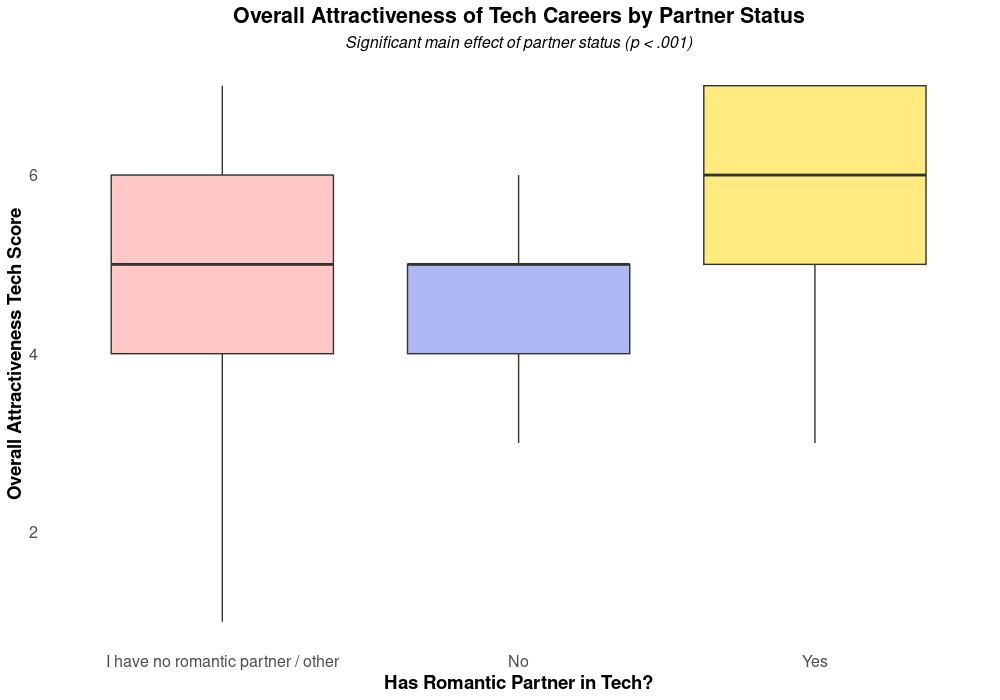

Participant Partner Employment in Technology and Attractiveness Ratings

For masculinity preferences, a significant effect was found for partner technology career status (F(2, 192) = 4.25, p = .0156). A post-hoc test revealed the difference was significant only for participants who were single versus participants who did not have a romantic partner in a technology career (M = 5.60 vs. M = 6.08) (p = .0139). No other comparisons were significant (all ps > .05).

A significant effect was found for long-term technology career desirability and romantic partner technology career status (F(2, 192) = 4.137, p = .0174). Single participants (M = 42.6) had significantly higher scores than those without partners in technology careers (M = 39.0, p = .0480). ANOVA results were not significant for short-term technology attractiveness nor technology career masculinity.

For single-item overall attractiveness of technology careers, the results were significant (F(2, 192) = 8.934, p < .001). Participants with no romantic partner (M = 4.98) had significantly higher scores than participants with a romantic partner who was not in a technology career (M = 4.44, p = .031) and lower scores than those with a partner in a technology career (M = 5.70, p = .032). Additionally, there was a significant difference between participants who did not have a romantic partner in a technology career and participants who did, with participants who did scoring significantly higher (p < .001).

Qualitative Response Word Clouds: Trades Careers

The most frequently used term in describing the attractiveness of trade careers was “work” at 31 occurrences. “Hands” occurred 27 times, taking the third spot for most frequently used words. “Physical” was fourth at 21 occurrences. Synonyms of words like “skills” (19) and “ability” (18) were frequently used. Synonyms of “strength” (16) and “masculine” (13) also occurred frequently. In our qualitative data, the attractiveness of trade careers is attributed to masculinity, physical strength, and the trade skills themselves.

The top two words used in describing what is unattractive about trade careers were “lower” (28) and “low” (24). These were often combined with “status” (15). “Dirty” was the third most-used descriptive term at 19 occurrences. Terms related to intelligence (8, 7 for “intelligent”) and education (9) were moderately used. Terms related to money (6) were used relatively infrequently, with almost no synonyms of “money” or “income” occurring in the qualitative responses. The perceived unattractiveness of trade careers in the qualitative data points primarily toward perceptions of lower status and lower intelligence.

Qualitative Response Word Clouds: Technology Careers

The most frequently used term in qualitative descriptions of the attractiveness of technology careers was “intelligence” at 46 occurrences. “Intelligent” had a separate 11 occurrences. “High” was the second most-used term at 22 occurrences (often in conjunction with words like “income”). The word “money” was the fifth most-used term, at 15 occurrences. Terms like “Pay,” “income,” and “earnings” were frequent. “Status” was mentioned 9 times, but relatively few status-related synonyms were used. The attractiveness of technology careers, in qualitative responses, seems to hinge primarily on intelligence and income.

The third most common word was “less” (21), which was often combined with adjectives such as “masculine” (16). Boring occurred frequently, at 16 occurrences, as did “nerdy” at (16). Synonyms of “nerdy” were very common. Terms like “physical” (11) and “physically” (11) were used frequently to describe perceived deficits in physical activity or ability. Overall, technology jobs suffer from the nerd stereotype: they are perceived as less masculine and less physical.

Result Summary

- Technology careers were rated as higher in long-term attractiveness than trade careers.

- No significant differences were found in the total short-term attractiveness of technology and trade careers.

- Trade careers were rated as higher in masculinity than technology careers.

- Women rated the short-term attractiveness and masculinity higher for technology careers than men believed women rated them. Women also rated the overall career attractiveness of both technology and trades higher than men believed women would rate them.

- Women with lower levels of education perceived trade careers as higher in long-term attractiveness and overall attractiveness.

- Politics and age were not significantly related to perceptions of career attractiveness.

- Within careers, participants who perceived trades as higher in long-term attractiveness also perceived trades as higher in short-term attractiveness and masculinity. The same pattern of intercorrelations existed for participants who perceived technology careers as higher in long-term attractiveness; they too perceived technology careers as higher in short-term attractiveness and masculinity.

- Participants who had partners in the trades perceived the trades as more attractive, while participants who had partners in technology perceived technology careers as more attractive.

- Qualitative descriptions of the attractiveness and unattractiveness of trade and technology careers fit our popular stereotypes about these careers.

Discussion

Technology careers were perceived as higher in long-term attractiveness than trade careers. In the qualitative data, intelligence and income were often cited to describe why technology careers are attractive. This is consistent with evolutionary theories of long-term mate selection, where intelligence and resource provisioning play a larger role in long-term mate formation. We also see some stereotype accuracy. In the qualitative data, trade careers were described as lower in intelligence. As outlined in the introduction, trade careers are actually associated with lower measured IQ on average.

Trades beat technology careers in ratings of perceived masculinity. The qualitative data also show masculinity and physical ability as an attractive trait of trades careers, whereas an absence of masculinity and physicality are described in the unattractiveness of technology careers. We have many different folk psychologies of masculinity, or what regular people out in the world think masculinity means. The more I research masculinity, the more I have come to believe that it is mostly defined by high sexual dimorphism. In other words, masculinity is primarily your physique. Men who are perceived as physically strong are perceived as more masculine. Conjure a picture of a Cloud Administrator and a Welder in your mind and think carefully about what their bodies look like to you. Is the Welder more muscular?

This data also shows some assortative preferences and the “positive illusions” effect. Women who had lower levels of education were more likely to see men in the trades as more attractive. Indeed, women with lower levels of education are actually more likely to date and marry men in the trades. Participants who had romantic partners in the trades also perceived trades as more attractive, while participants who had romantic partners in technology perceived technology careers as more attractive.

I have written about the positive illusions effect in the past. It is one evolutionary mechanism for the formation of long-term pair bonds. You see your romantic partner, along with whatever it is that they do, as more attractive than others see your partner. We also know that while stated and revealed preferences are not always perfectly lined up, they don’t end up being opposites to one another. People actually do pick romantic partners with the traits that they say they like. That people end up in relationships with people who have the traits that they like, or in this case the careers that they like, is neither a surprising nor a new finding.

Also worth mentioning are the intercorrelations between long-term attractiveness, short-term attractiveness, and masculinity. This has occurred in every study I have run, as well as much research in general floating around out there. When someone rates a person, face, or vignette high in long-term attractiveness, they also tend to rate it high in short-term attractiveness and masculinity. It was never the case that there were diametrically opposed long-term “types” versus short-term “types.” There are differences, but what people desire for long-term relationships tends to be what they desire for short-term relationships, and vice versa.

What’s the practical takeaway here? By knowing what stereotypes are associated with trades and technology careers, you can work to “break the mold” so to speak. If you’re in a technology career and you know that the stereotype is that people in tech are limp-wristed nerds who don’t know how to fix anything, maybe hit the gym and learn some do-it-yourself skills. If you’re in the trades and you know that the stereotype is a low-status oaf who can’t read so well, maybe try to signal status (for example, dressing well or having high-status-coded hobbies) or intelligence (make your trade into an art). There are positive and negative perceptions of trade and technology careers, so highlight the positive and offset the negative.

References

Anni, K., Vainik, U., & Mõttus, R. (2024). Personality profiles of 263 occupations. Journal of Applied Psychology.

Horwitz, T., & Keller, M. (2022). A comprehensive meta-analysis of human assortative mating in 22 complex traits.

Wolfram, T. (2023). (Not just) Intelligence stratifies the occupational hierarchy: Ranking 360 professions by IQ and non-cognitive traits. Intelligence, 98, 101755.

5 comments

Lmao, who pays for this horse shit

Really? Antisocial Nerds are attractive?

A lot of resistance to simple data, I see.

While the data is indeed from a small sample, it makes a lot of sense, as do the suggestions.

If I wouldn’t be married yet, I WOULD pay for this.

The end suggestion is top notch; I can say it because I applied it on my own, and it solved all my problems: as a brainy nerd with social anxiety, I started doing things that “counter-balanced” that identity since very early on, from social drinking to weight training, and finally a lot of talking and debating (first with “safe” people, then just about anyone).

I became comfortable in my skin, sociable, and fairly muscular, but keeping what makes the “antisocial nerd” attractive.

Except the high income job, that came much later for me, and yet I got married to my soulmate long before that.

Notice that Uni professor is nowhere to be seen.

You are a jew faggot who gets zero pussy lmao kill yourself kike