Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

“70% of divorces are initiated by women.” This has become a meme statistic. I have seen this repeated over the years with increasing embellishment. One day it’s 70%, the next 80% — soon it will be 105%. Women are initiating all of the divorces and even annulling marriages that have yet to exist. They are going into graveyards and performing divorce ceremonies for the deceased. Women are having weddings for their pets only so they can get divorced. Little girls are making Barbie run out on Ken.

Despite how popular it is to regurgitate this statistic, I rarely see it referenced alongside the research it is derived from. Most people have probably picked it up from headlines or passively learned it through repetition on social media. This is why I call it a meme statistic.

Is it true? In this article I will review the literature that gives us statistics like this. What seems to be true is that women initiate more divorces.

I will also review the literature discussing why women initiate more divorces. The real error is not saying “70% of divorced women asked for the divorce” when it’s 62.31% or some other figure. That is just nitpicking. The real error, commonly made, is to assume that whoever initiates a divorce is at fault for it.

The whole discourse is driven by an ideological “battle of the sexes.” People want to blame someone. Men want to blame women and women want to blame men. I won’t say that the discourse is symmetrical; “women initiate most divorces” is used to blame women mostly. However, the desire to shift culpability onto the “other” is a feature of human psychology.

The point is that knowing who initiates a divorce is minimally informative. It does not tell you why a divorce happened. It does not tell you what events doomed the relationship. It does not tell you who is at fault — which is typically what those who regurgitate this statistic are trying to make it say.

Who is still an important question. It gives you a starting point to ask further questions. I will try to answer the question of who first. We will see if it is true that 70% of divorces are initiated by women.

However, the more important question is why people divorce. A few common causes of divorce are: infidelity, physical abuse, and drug addiction. You wouldn’t blame a man for divorcing a cheating wife. You wouldn’t blame a woman for divorcing a man who hits her. I will describe the why of divorce, the explicit reasons, in the second section.

The why of divorce does not stop at the explicit reasons for divorce, however. Heritable personality traits — your own genetics — shape your likelihood of divorce. Premarital behavior unrelated to your current relationship steers future divorce outcomes. Many factors predict and influence future divorce. These are extremely important for understanding divorce. In the third section, I will review the literature on personality, behavioral, and genetic contributions to divorce.

You will find lots of ammunition in this article for whatever side of the battle of the sexes you are on: team pink or team blue. Hopefully, however, by the time you finish this article you will realize divorce is very complex. You don’t want to slip into the univariate fallacy if you really want to understand divorce. Many factors contribute to divorce.

Are 70% Of Divorces Initiated By Women?

First, are 70% of divorces really initiated by women? You can find a multitude of headlines that give you this figure. However, the results across representative research statistics are less clear. What seems to be fairly consistent is that women initiate divorce more.

What is divorce initiation?

First, what do we mean by divorce initiation? This means women are the ones to ask for a divorce first. The why still remains. We are simply asking who.

To clarify further: the statistics are usually based on self reports of who initiated a divorce. The questions asked in divorce literature may be as simple as: “who initiated the divorce,” “who wanted the divorce more,” or “who first asked for a divorce.”

This is a common single item question I have seen used in multiple papers on divorce initiation:

“In the divorce process, it sometimes occurs that one of the two spouses takes the first step. In your case, who first made the decision to separate? Was that you, your partner, or you and your partner more or less simultaneously?”

Divorce initiation is usually not who filed for divorce.

Parker et al. (2022) developed a divorce initiation inventory to assess divorce initiation across dimensions. There are many different measures used in research that ask divorced participants some variation of “who did it.” I won’t go into detail on every question item that has been used, but I want to make it clear that when we talk of divorce initiation we are usually not talking about who filed for the divorce.

This is a common misconception people have when reading the “70%” statistic in the media. People seem to assume this figure is derived from divorce filings — paperwork found in a file drawer you can dig up. It is not the case for most research. In the United States, divorces are done on a county-by-county basis and records are dispersed, so gathering a representative sample (at least for the USA) would be difficult. Who filed for a divorce is also a different question from who initiated a divorce. Filings, for example, would only tell you who is responsible for the paperwork.

If I break up with my wife and make her file, this would be reflected as female initiation. Yet, it would paint the wrong picture of who dumped who. To know that you must ask the couples.

This is complicated further by the fact that the United States has few mutual filing options, while much of Europe does. For example, in Spain 76.6% of divorces were by mutual agreement (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica, 2017). In Belgium, 80% are by mutual consent Baitar et al. (2012). If you go by filing statistics such as these, you would not be able to say women initiate more divorces. You’d conclude that most divorces are mutual.

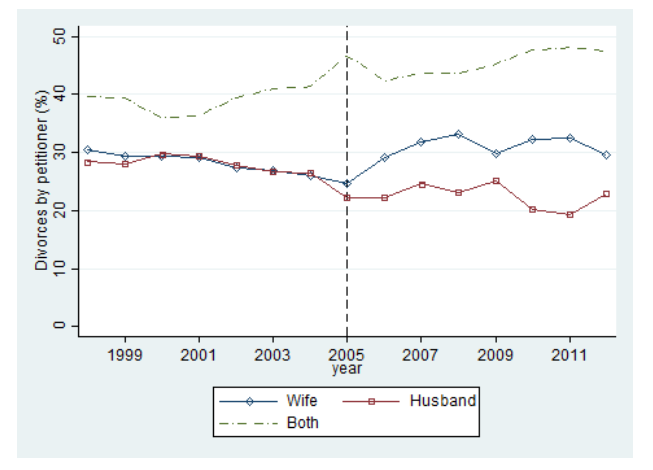

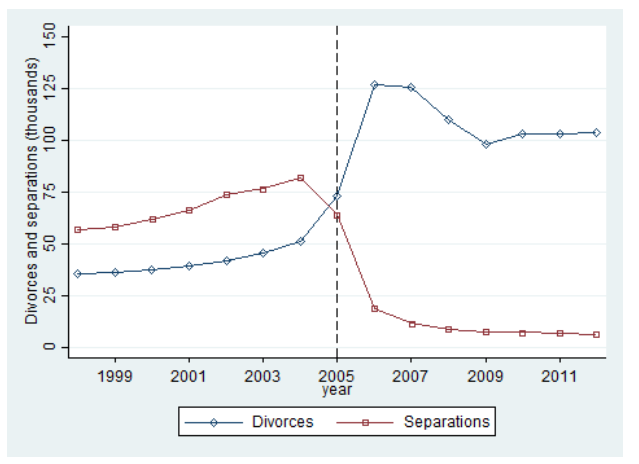

This chart is from a recent paper showing all divorce filings in Spain between 1998 and 2012 (Alonso-Borrego & Pomares, 2023). This is very revealing, because it tracks a change in divorce filings following Spain’s implementation of what was called the “express divorce” law. This was a “no-fault divorce” law that made the divorce process among the fastest and easiest in the European Union. Spain currently has the highest divorce rate in the European Union, at close to 80%.

Here we see that women initiated divorce proceedings slightly more than men did, by about 7%. A majority of filings, however, were initiated by both parties. This likely does reflect the trend of women desiring the divorce more, but we can’t really know, and if we only looked at filings it would show women initiate approximately 30% of divorces while men initiate approximately 25%

Rosenfeld (2017)

If you Google “women initiate 70% of divorces,” most results point back to a study by Rosenfeld (2017). This seems to be the study most captured by the media. Given that, let’s look at this one first.

Rosenfeld’s (2017) data is from the How Couples Meet and Stay Together (HCMST) survey, a nationally representative telephone sample of Americans. This survey asked one question with three potential responses:

“Between you and (partnername), who wanted the (divorce/separation/breakup) more?” Respondents were offered 3 alternatives: “I wanted the (divorce/separation/breakup) more;”(Partner name) wanted the (divorce/separation/breakup) more;” and “We both equally wanted the (divorce/separation/breakup).”

This survey had a sample of 92 divorced participants. 56 divorces were reported as wanted by the wife, 18 divorces by the husband, and 18 divorces were mutual.

This means 60% of respondents reported that the wife initiated the divorce, 20% reported it was mutual, and 20% reported it was the husband.

How was the 70% figure derived? Rosenfeld (2017) assigned one half of a scale point for “mutual break-ups” to men and women. Thus, an additional 10% was added to the female initiation figure and an additional 10% to the male initiation figure.

Rosenfeld reported that 70% is statistically significantly different from 50%. This means we can reject the null hypothesis. In other words, we conclude women initiate most divorces.

However, without adding “mutual break-ups” to the female score, and beginning with the actual statistic of 60%, do we still get a significant result?

With a sample size of 92 and generalizing to the entire divorced population (28.77 million Americans), we get a margin of error of 10.1%. From this, we know our margin of error overlaps with the mean of our comparison group (50%). We cannot reject the null hypothesis.

In other words, we can’t know if women initiate most divorces — at least not from this paper. More people reported that the wife initiated the divorce, but given the small sample size we do not know if this is due to chance or random error.

It’s perhaps unfortunate that the paper everyone has latched onto has a sample size of 92 and a methodology that looks a little like playing with the data to achieve a significant result. Nonetheless, this doesn’t debunk the statistic, or at least it doesn’t debunk the general trend that women initiate more divorces. There is a lot more research out there.

Sayer et al. (2005)

A study by Sayer et al. (2005) used the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH), a large nationally representative survey that asks the following question:

“Sometimes both partners equally want a marriage to end, other times one partner wants it to end much more than the other. Circle the number of the answer that best describes how it was in your case.”

In the NSFH2, an updated survey with additional responses, participants may also respond to this question:

“I wanted the marriage to end BUT my husband/wife did not; 2) I wanted it to end MORE THAN my husband/wife did; 3) We both wanted it to end; 4) My husband/wife wanted the relationship to end MORE THAN I did; or 5) My husband/wife wanted the marriage to end BUT I did not.” (Sayer et al., 2005).

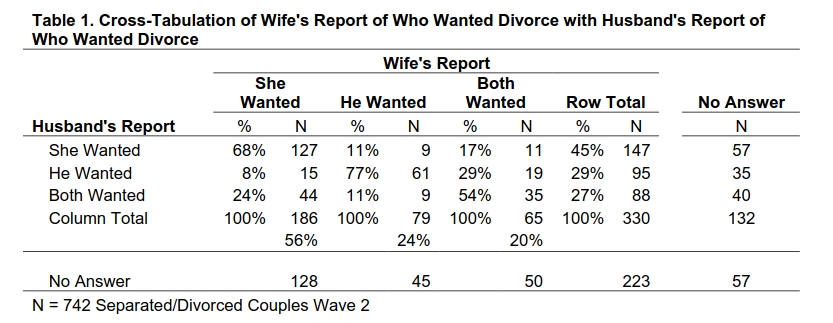

Sayer et al. (2005) report the following results from this dataset. This table shows the level of agreement between husbands and wives on report measures:

When women reported that they wanted a divorce more, 68% of husbands agreed. When women reported that the husband wanted a divorce more, 77% of husbands agreed.

This raises an important point: we don’t see full agreement between divorced dyads on who actually initiated a divorce. Divorcees do tend to agree somewhat across measures, but the high level of disagreement muddies the waters. This makes it hard to know which partner is really at the root of divorce initiation.

Additionally, when disagreement occurs, it is more often the case that one party thinks the divorce was mutual. It is rare that there is disagreement in the form of both spouses believing they initiated it. This restores some confidence in the reports — we don’t have to pick between believing the husband or wife.

In Sayer et al. (2005), women initiated divorce more (56%), but it was not 70%. This sample is also large enough (N = 330) that we can calculate the margin of error (5.29%) and rule out that the difference may be due to chance, unlike the previous paper.

However, 56% may be close enough to pose a problem for the hypothesis that women initiate more divorces for another reason. To illustrate, assume women lie 100% of the time. We will only trust reports where men say the woman initiated it. This brings female divorce initiation down to 45.5% (the row total for men in the chart).

Of course, it is probably not the case that 100% of women lied. However, disagreement over the nature of the divorce makes these figures less clear. We will see this pattern repeated in much of the research below, as well. Wives report that they initiated divorce more than husbands report that their wives initiated divorce.

Additional research on divorce initiation

Hawkins et al. (2012) found that 66% of women reported that they initiated the divorce process. 33% of men reported that they initiated the process. 19% of men and 12% of women reported that the divorce was initiated by both parties. Again, we see some inconsistency in partner perceptions of who initiated.

Wang and Amato (2000) found a moderate correlation with gender and the desire for a divorce (r = .42), with women having wanted a divorce more. In Kerela, India, 68.2% of divorces were initiated by women (Vasudevan et al., 2015). This is an interesting dataset, because India has one of the world’s lowest divorce rates. Yet, we still see a pattern of women initiating more.

Buehler (1987) contacted a random sample of divorcees and found that 69% of women and 74% of men reported “being the one who left.” These were not divorced pairs, so it isn’t necessary that the total must fall close to 100%. However, given the random sampling it is puzzling that both men and women report high initiation of divorce. This may reflect differences in the way that participants interpret a question. As we will see in the subsequent section, divorced husbands and wives tend to agree on the reasons for a divorce.

Across two separate Danish samples, Hald et al. (2020) asked: “Who initiated your divorce?” This paper did not report descriptive statistics, raw numbers or percentages, for who initiated a divorce. However, they did report that there was no statistically significant gender difference between who initiated the divorce.

This does not mean that it was literally 50/50 (an assumption affirming the null result). What we can glean at best is that, given the large sample size (N = 1564), it is unlikely that the difference that did exist was large. Men and women would have reported initiating the divorce at relatively similar rates.

In a large representative sample from the Netherlands, Kalmijn et al. (2006) found that women reported initiating the divorce 61% of the time. Men, however, reported that their wives initiated the divorce 46% of the time. This is similar to the 45% figure for men reporting their wives initiated the divorce in Sayer et al. (2005). Reporting a mutual divorce was rare — about 10% for both men and women. Again we have a puzzle. If we listen to Dutch men, women do not initiate most divorces. If we listen to Dutch women, women initiate most divorces!

Note, this is the same problem we have seen in the previous statistics. How can we reconcile it? Maybe we can’t. According to Kalmijn et al.:

“On the one hand, women may have had a tendency to protect their self-esteem by claiming initiative that they in fact did not have. On the other hand, men may attribute the initiative to their wife even if they themselves took the first step. It is most likely that a combination of the two biases occurs.”

Ponzetti et al. (1992) found that 42% of couples disagreed about who initiated the divorce. 71% of wives reported initiating the divorce, while 43% of husbands reported being the initiator, and 21% said the divorce was mutually instigated. Interestingly, all couples agreed who moved out of the home: the husband left the home 64% of the time. This may indicate that reporting is not compromised, but that there is disagreement between some husbands and wives in their views on who broke up with who.

When I write about the psychology of dating a common objection is that research often relies on self reports. Further, some seem especially skeptical to trust the self reports of women. However, if you went by the reports of men exclusively you’d see results that look even more mixed. Across these papers, men tend to claim the ex-wife initiated it less than the ex-wife does.

What seems true based on the research overall — women initiate slightly more divorces. 70% may be an estimate at the high end of the range, but the sex difference in divorce initiation is real. We will see why below.

Reasons Cited For Divorce

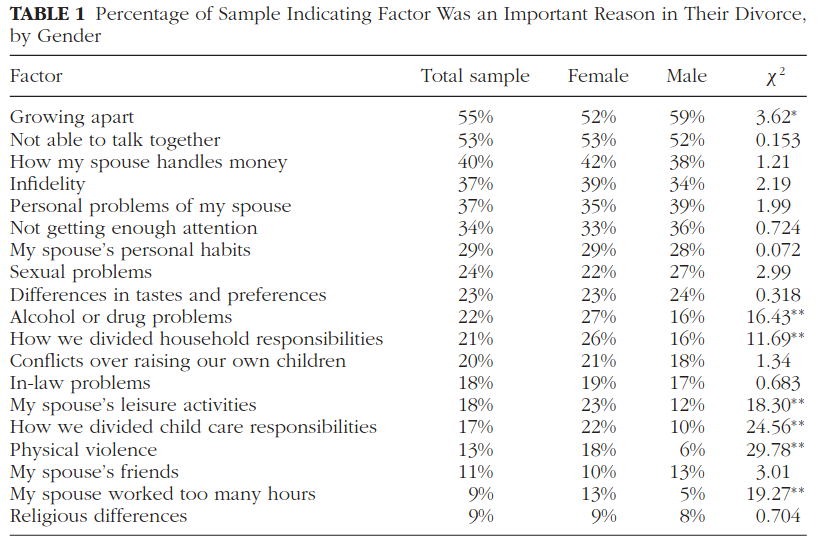

Hawkins et al. (2012) assessed a large sample (N = 886) of divorcing couples. Below are the reasons men and women gave:

Agreement (the nonsignificant results) and sex differences (the significant chi-square results) are both informative. Divorcing couples tend to agree when there are problems with: communication, money, infidelity, personal problems, attention, and sexual problems.

This is important, because it demonstrates low asymmetry in reasons for divorce. Divorcing couples know what the problems are and agree. It usually is not a case of “she divorced me and I have no idea why.”

Alcohol, leisure activities, child care responsibility, physical violence, and work show significant differences. This may reflect a different perception of the problem, or it might reflect sex differences in behavior. For example, women may report “worked too much” because men work more. Women might also report “physical violence” more if men commit more physical violence, or “alcohol and drug problems” if men have more substance abuse problems than women do.

Going forward to subsequent research, I want you to keep something in the back of your mind — men and women are behaviorally different in many ways. There are large sex differences between men and women in physical aggression (Archer, 2004; Hyde, 1984), infidelity (Dreznick, 2002; Wang, 2018), and substance abuse (US DHS, 2016). However, research has also called into question the one-sided nature of domestic violence. Women may be as prone to this as men and about half of all cases involve mutual abuse (Archer, 2000; Whitaker et al., 2007).

Even so, sex differences in aggression may be qualitative. For example, men may be more likely to cause serious harm due to being physically stronger (Archer, 2002). Relationship dissolution in response to physical abuse may also show a sex difference; men and women may also experience the consequences of abuse and victimization differently. Men, due to larger size and strength, may be less likely to be recipients of physically damaging violence. For example, women may be less likely to receive punishment (Felson & Pare, 2007). The legal fallout of domestic violence may add another variable to the picture.

Domestic violence is a complex topic. Differences in the way that it is perpetrated, experienced, and reacted to may explain some of the difference in reasons for divorce. Across two separate Danish samples, Hald et al. (2020) found that 28% and 26% of divorces involved infidelity and 6% and 5% involved physical violence. Women were also more likely to cite infidelity and violence in the relationship as reasons for divorce (Cohen’s d of .32 and .53). Regardless of which of the two sexes perpetrates more violence, women may be more inclined to end a relationship over it.

The role of physical violence in divorce is a global trend. In countries where divorce is less common, violence often represents one of the top reasons listed for divorce. In an Iranian sample, 84.3% of divorce cases involved domestic violence (Bolhari et al., 2012). In Ethiopia, it was as high as 91.7% (Adamu & Temesgen, 2013). In Indonesia, violence was associated with a 67% increase in divorce (Syamsiar & Hasmawati, 2021; Putra et al., 2021). Half of marriages in India’s divorce courts involved abuse (Vasudevan et al., 2015), while in the UAE violence was the second most reported reason for divorce (Rehim et al., 2020). In Turkey, 29.8% of divorces involved violence (Coşkun & Sarlak, 2020).

The further West you go, the lower the proportion of divorces that involve abuse. However, in Western nations it is still high. Coşkun & Sarlak (2020) reported 29% of divorces involved physical abuse in a representative sample from the United States. Why do we see abuse as a less common reason for divorce in the West? Well, it could actually occur less in the West for one. Additionally, the West may see more divorce for less “serious” reasons. It’s likely a mixture of the two. In any case, domestic violence is a part of the global divorce landscape.

In all of the studies cited above, infidelity also emerged as a top predictor of divorce. Janus and Janus (1993) found that 43% of all divorced dyads had experienced infidelity at some point within their marriage. Marin et al. (2014) found that, of couples who entered marital therapy, those who had experienced a past act of infidelity within the marriage were twice as likely to dissolve the marriage within the next five years (53% versus 23%).

Balderrama-Durbin (2017) examined the course of infidelity in active military Airmen during deployment. The rate of infidelity for the general community during this period was 1-4%. However, for active service members it was 22%. 75% of Airmen who engaged in infidelity were divorced 6-9 months post-deployment, while only 5% of Airmen who had not engaged in infidelity divorced.

That there is an association with divorce, infidelity, and abuse probably won’t surprise you. However, there is a point here. In the discourse on who initiates divorce, people routinely seem to forget that divorce is not random. The way people discuss it, you would think divorce is something that just happens. However, the decisions that people make contribute to divorce.

Do Divorced Spouses Agree On The Reasons?

“70% of divorces are initiated by women” is often presented in a way that would make you think 70% of men don’t want a divorce. In essence, people seem to think this means wives want these divorces while husbands do not. Alternatively, it is sometimes presented in a way that you would think most men are blindsided by divorce. They had no idea something was wrong.

This is not what the research shows. Men and women agree in the case of most divorces. Marital dyads are well aware of the problems in their relationship, big or small, that precede a divorce.

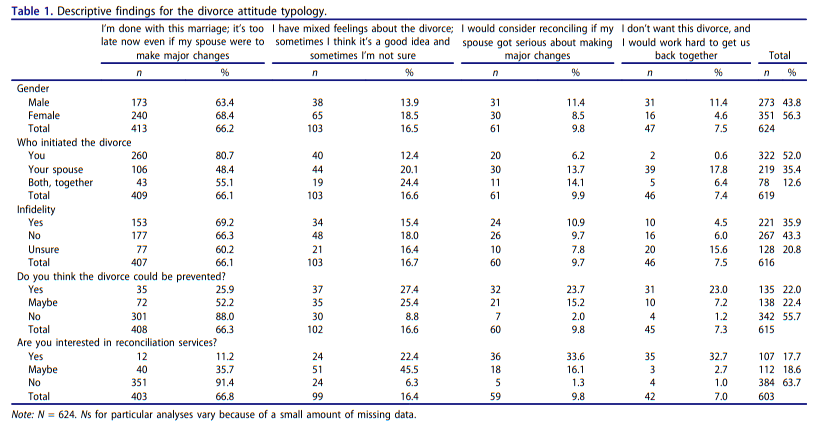

Doherty et al. (2016) asked divorcing couples to indicate their agreement with four questions:

- I’m done with this marriage; it’s too late now even if my spouse were to make major changes.

- I have mixed feelings about the divorce; sometimes I think it’s a good idea and sometimes I’m not sure.

- I would consider reconciling if my spouse got serious about making major changes.

- I don’t want this divorce, and I would work hard to get us back together.

Here are the results:

63.4% of men and 68.4% of women agreed with the first statement — “I’m done with this marriage.” 13.9% of men and 18.5% of women had mixed feelings, and 11.4% of men and 8.5% of women said they would consider reconciliation if their spouse made changes.

Only 11.4% of men and 4.6% of women said they did not want the divorce and that they would work hard to fix the marriage.

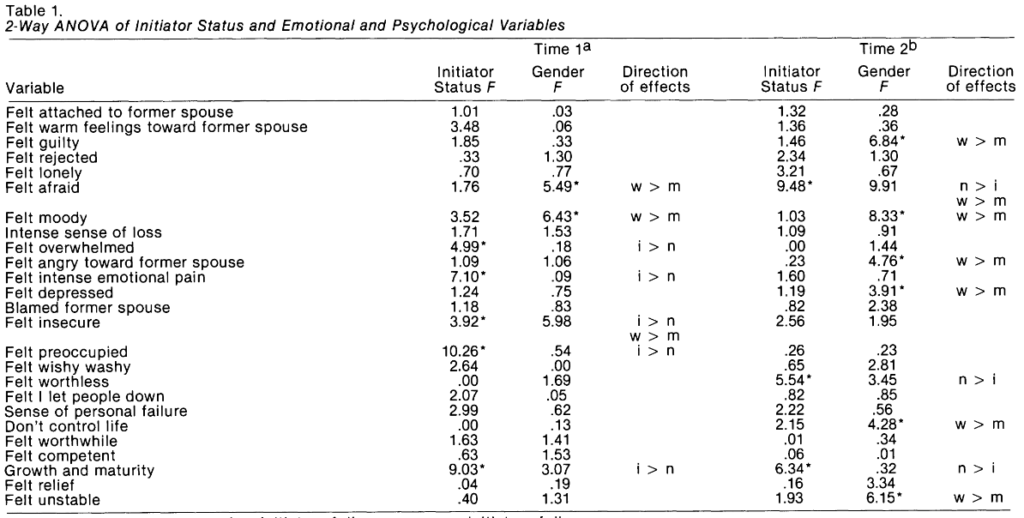

Buehler (1987) examined feelings of men and women following a divorce. In only 2 out of 25 variables examined did men and women feel differently. In the second wave, 6 out of 25. Below are the results:

Women felt more afraid and more moody. An important variable here is blamed former spouse. Here we see no effect of gender. Men didn’t blame women for the divorce and women didn’t blame men for the divorce. Similarly, there was no difference in feeling rejected, feeling anger toward a former spouse, or feeling relief. In the second wave, anger and guilt did emerge however, with women feeling more of these emotions than men.

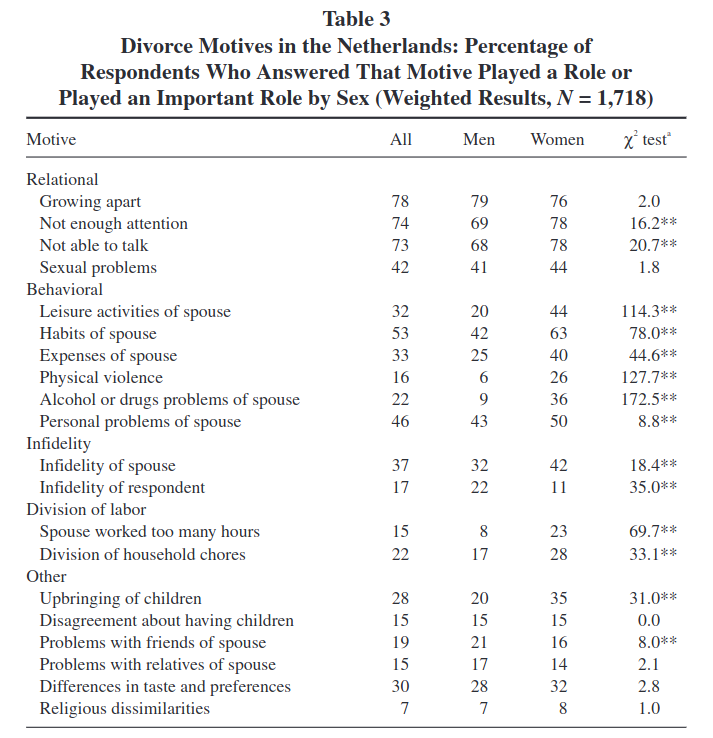

In a large sample from the Netherlands, de Graaf and Kalmijn (2004) examined sex differences in agreement on divorce:

The top motives for divorce tend to see the largest agreement between men and women. The motives are also not dire. People divorce because they grow apart. Men and women agree that they have grown apart.

Here are where we do see sex differences: women report, of their male spouses, more problematic leisure activities, more problematic habits, more physical violence, more alcohol or drug use, and more infidelity. Further, men report their own infidelity at a rate twice that of women. Men also report problematic behaviors of their female spouses at lower rates.

This is important, because some people will claim women are simply lying. But no, men even report this of themselves.

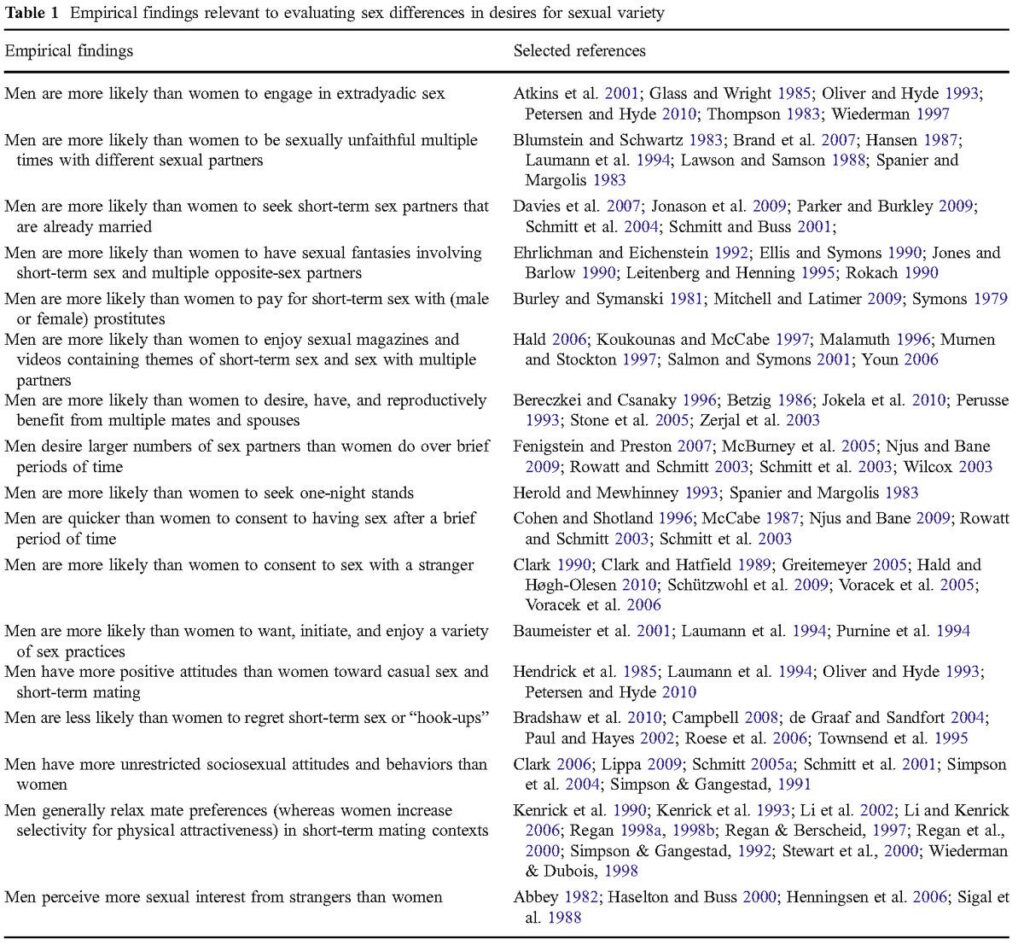

This is what you should expect given well-researched sex differences in sexual behavior, by the way. A chart listing many of those:

There is a highly consistent trend. Men are more likely to cheat.

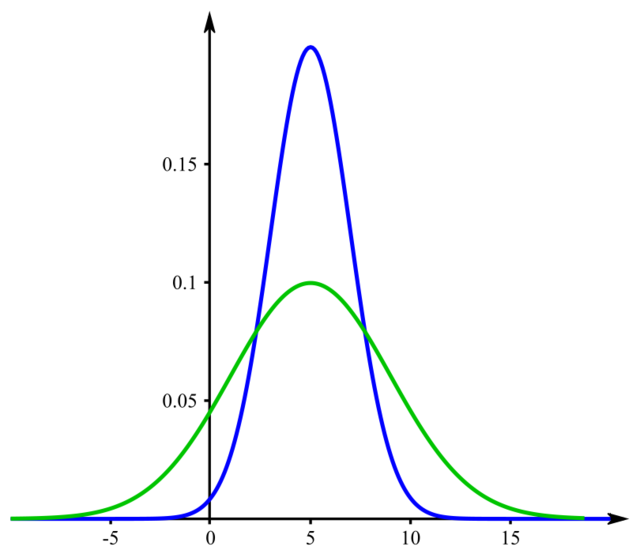

An obvious explanation for the sex difference in divorce initiation is the sex difference in unfaithful behavior. It may be a bitter pill to swallow that men, on average, engage in more problematic behaviors during a marriage that lead to divorce. However, this is also consistent with the greater male variability hypothesis.

Men show a wider distribution of traits and behaviors. For example, men show greater variation in risk-taking behavior (Thöni, C., & Volk, 2021; Cross et al., 2011) and risk-seeking behavior is associated with short-term mating orientations (Fetchenhauer & Rohde, 2002) and substance abuse. Life-course persistent antisocial behavior, associated with promiscuity, is almost exclusively male, represented at the left tail of the distribution that has no female overlap (Eme, 2009). From an evolutionary perspective, in terms of reproductive fitness, men have more to gain from extra-pair copulation. Consistent with this we see sex differences in both behaviors and attitudes related to infidelity (Copping & Richardson, 2020).

Willingness To Fix The Marriage

Assessing couples’ willingness to fix the marriage is another way to understand who wanted to divorce more. If one partner wants it more, for example, we should see less willingness to enter a reconciliation program, counseling, or therapy. Conversely, if one partner does not want it we should see high openness to intervention.

In a large study of divorcing couples, only 17% of men and 12.4% of women stated they believed their marriage could be saved (Doherty et al., 2011). 17.3% and 14.7% of men and women respectively said they would be willing to enter a reconciliation program before divorce. Hawkins et al. (2012) similarly found only 10% of divorcing couples and 20% of individuals were interested in a reconciliation service.

In a study of African American marriages, 61% of men and 46% of women reported being unwilling to seek professional help for marital problems. Bowan and Richman (1991) similarly found a sex difference in willingness to seek marital therapy, with men being less willing than women. Men were also less likely to consult friends or family for marital help.

Doss & Atkins (2003) identified three steps to marital intervention: problem recognition, treatment consideration, and treatment seeking. Wives were more likely than husbands to complete all three steps. Further, wives completed each step at an earlier date than husbands when husbands did complete them.

You may wonder how well marital therapy really works. Unfortunately, a sad fact about psychology is that most therapy (for anything) doesn’t work that well. At least, if you define “work” as producing a full “cure.” Personality disorders are stable across the lifespan. Major depression rarely goes into full remission. Most addicts don’t completely quit using drugs following rehabilitation. Marital therapy, perhaps surprisingly, works as well or better than treatments across other fields of psychotherapy (Shadish et al., 1995).

However, psychotherapy doesn’t have to work for everyone, perfectly, to be valuable. A treatment that improves outcomes by 20% is still superior to nonaction that does not improve outcomes at all. More importantly for this discussion, the willingness to seek treatment tells us about the willingness to save a marriage. Women may initiate more divorces, but they also show a greater willingness to save their marriages — at least insofar as this is indexed by seeking marital help.

Personality and Genetics of Divorce

Behavioral genetics gave us the 50-0-50 rule, the observation that 50% of the variation in human traits and behaviors is influenced by genetic factors, 0% is influenced by shared environmental factors, and the remaining 50% is attributable to non-shared environmental factors. This will vary trait-by-trait, but the rule broadly characterizes environmental and genetic contributions to personality.

Using the Minnesota Twin Database, Jocklin et al. (1996) estimated that 30% to 42% of the heritability of divorce risk was determined by genetically-influenced personality traits. Positive and negative emotionality, as well as constraint, are heritable and contribute to divorce risk. McGue and Lykken (1992) similarly found a high heritability of divorce using the same dataset, of approximately 50%. Women tend to be higher in negative emotionality while men tend to be lower in constraint.

Jerskey et al. (2010) examined 6225 male twin pairs from the Vietnam Era Twin Registry. Heritability for divorce was estimated at 58%. Remarkably, almost all of the variance in divorce was independent from the variance in getting married. What does this mean? It means that divorce isn’t simply something that happens to you when you are married. There are individual differences in genetics between people who get divorced and stay married.

Given this, it may not surprise you that other behaviors related to divorce are also heritable. For example, both infidelity and number of sexual partners show moderate heritability (Cherkas et al., 2004; Zietsch et al., 2015). Domestic violence also has a genetic component (Stuart et al., 2014). Substance abuse has a heritability estimated at close to 50% (Deak & Johnson, 2021).

Eysenck (1980) found associations with scores on the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire and divorce, with individuals high in neuroticism and psychoticism being more likely to divorce. In general, women are higher in neuroticism and men are higher in psychoticism.

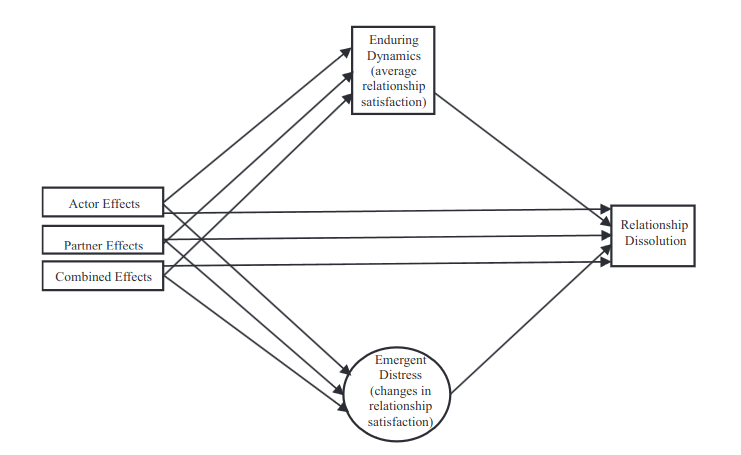

In a large, representative, longitudinal study of Americans, Solomon et al. (2014) identified two personality-mediated trajectories to divorce: enduring dynamics and emergent distress. In enduring dynamics, Big Five personality traits shape the trajectory of a relationship from square one. Bad personality, bad relationship. In emergent distress, personality shapes how relationship distress emerges and how couples navigate it. In both models, personality shapes how you behave and how you respond to new events in a relationship.

In representative samples across three European countries, Boertien and Mortelmans (2018) found that Big Five personality traits that predict divorce have remained stable predictors across time. Individuals low in conscientiousness and high in neuroticism are more likely to divorce. This may reveal another puzzle piece in the divorce picture: women score higher in neuroticism on average (Weisberg et al., 2011) and neuroticism is linked to lower marital satisfaction and higher divorce risk (Sayehmiri et al., 2020). Conversely, men tend to score lower in conscientiousness. Here we see sex differences in heritable personality traits that may contribute to divorce in different ways.

Brennan and Shaver (1998) found associations with clinical psychopathology, attachment styles, and parental divorce. Most, if not all, clinical disorders have a genetic component (Smoller et al., 2019), as do attachment styles (Brussoni, 2000). The children of divorced parents were less likely to have a secure attachment style and more likely to be represented within the range of clinical disorders.

Further, there are sex differences in attachment styles; men are more likely to be avoidant, women are more likely to be anxious (Del Giudice, 2019). A study by McNelis & Segrin (2019) found that avoidant attachment predicted divorce about twice as well as anxious attachment. Avoidant and anxious attachment also have small to moderate correlations with Gottman’s (1998) “Four Horsemen:” four interpersonal behaviors that are robust predictors of divorce.

The Dark Triad, a construct of antisocial personality, also predicts divorce (Weiss et al., 2018). Men score higher on DT measures. Additionally, a high number of past sexual partners predicts divorce for both men and women (Smith & Wolfinger, 2023). This is an association that remains robust even when controlling for expected third variables, such as race, religion, and socioeconomic background. This is one variable that people like to interpet causally. However, the behaviors and personalities of individuals who are highly promiscuous can be quite different from those who are not. For example, infidelity and promiscuity are correlated (Garcia et al., 2010; Pinto, 2015). Sociosexuality, a measure of one’s willingness to have multiple sexual partners, predicts infidelity as well (Rodrigues et al., 2017).

The take-home point from this section: divorce risk is not evenly distributed and does not emerge from a blank slate. Men often interpret “women initiate 70% of divorces” as “if I get married, I have a 70% risk of getting dumped.” Not so.

Your own individual divorce risk may be much lower or, unfortunately, much higher. This depends on your behavior. It depends on the behavior of your partner. Additionally, given moderate levels of assortative mating for behavioral similarity in a romantic partner, it is likely that your partners will be similar to you. People with behaviors that raise divorce risk find romantic partners who often express similar behaviors.

Environmental Contributions To Divorce

People love to blame “society” for increasing divorce rates. It shifts accountability away from their own interpersonal behavior. Nonetheless, it isn’t wrong that divorce outcomes have environmental associations.

The most obvious environmental contribution to divorce is simple: does the environment that you are in even allow divorce in the first place. In the first section, I mentioned that India has one of the world’s lowest divorce rates. Until recently, India had no family courts. In the Islamic world, we see very low divorce rates as well. The simple explanation is that neither men nor women have the freedom to unilaterally petition a divorce. The legal and cultural pressures limit divorce.

Meanwhile, Spain went from having one of Europe’s lowest divorce rates to the highest. This is marked clearly by the introduction of Spain’s “express divorce” law (Alonso-Borrego & Pomares, 2023).

During the Franco era, divorce in Spain was practically prohibited. The first reform to Spain’s divorce law came in 1981 and required a five year separation period. Legal separations were already increasing, but the introduction of the “express divorce” law in 2005 saw divorce petitions skyrocket for a period of three years. Past that point, divorces seemed to stabilize at the rate that separations were increasing.

Additionally, when women are promoted or begin to make more money, divorce rates increase (Folke & Rickne, 2020). There are multiple reasons why this may be. First, financial stability allows someone to leave a relationship. Second, women may become less satisfied with a partner who earns less due to incongruence with expected gender roles or due to an evolutionary tendency to prefer men higher in status.

There are those on the ideological fringes who see this and say: prohibit divorce, don’t allow women to work. Would this reduce divorce rates? It might. Nonetheless, it’s a facile cope. It’s not going to happen, for one. Most people don’t want it. Nor would it ever make a woman love you. You would simply find yourself stuck in an unhappy and sexless marriage with a woman who can’t stand the sight of your face.

Conclusion

This article is long and yet it only scratches the surface. There are many more popular divorce tropes I may add or address later: that it’s for child support (the average monthly payment is only $300), alimony (fewer than 10% of all divorced couples receive it), or a big cash windfall (most divorcees have nothing to split). The point is that you should think about why people divorce, not who is at fault. Further, if you’re really worried about your own potential divorce — and not merely trying to score points for team blue or team pink — then you need to look inside yourself. You can’t change society nor the entire opposite sex. You can change yourself and choose a partner wisely. Understanding the interpersonal correlates and causes of divorce can help you to do that.

References

Adamu, A., & Temesgen, M. (2013). Divorce in east Gojjam zone: rates, causes and consequences. Wudpecker J. Soc. Anthropol, 2, 8-16.

Alonso-Borrego, C., & Pomares Varo, G. (2023). Breaking the marriage trap: unilateral divorce and its effects on labor supply of married women.

Amato, P. R., & Previti, D. (2003). People’s reasons for divorcing: Gender, social class, the life course, and adjustment. Journal of family issues, 24(5), 602-626.

Archer, J. (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin, 126(5), 651.

Archer, J. (2002). Sex differences in physically aggressive acts between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and violent behavior, 7(4), 313-351.

Archer, J. (2004). Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic review. Review of general Psychology, 8(4), 291-322.

Aston, J. (2022). Petitions to the Court for Divorce and Matrimonial Causes: A New Methodological Approach to the History of Divorce, 1857–1923. The Journal of Legal History, 43(2), 161-186.

Balderrama-Durbin, C., Stanton, K., Snyder, D. K., Cigrang, J. A., Talcott, G. W., Smith Slep, A. M., … & Cassidy, D. G. (2017). The risk for marital infidelity across a year-long deployment. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(5), 629.

Baitar, R., Buysse, A., Brondeel, R., De Mol, J., & Rober, P. (2012). Toward high‐quality divorce agreements: The influence of facilitative professionals. Negotiation Journal, 28(4), 453-473.

Bolhari, J., Ramezanzadeh, F., Abedinia, N., Naghizadeh, M. M., Pahlavani, H., & Saberi, S. (2012). To explore identifying the influencing factors of divorce in Tehran. Iranian journal of epidemiology, 8(1), 82-92.

Boertien, D., & Härkönen, J. (2018). Why does women’s education stabilize marriages? The role of marital attraction and barriers to divorce. Demographic research, 38, 1241-1276.

Boertien, D., & Mortelmans, D. (2018). Does the relationship between personality and divorce change over time? A cross-country comparison of marriage cohorts. Acta Sociologica, 61(3), 300-316.

Bowen, G. L., & Richman, J. M. (1991). The willingness of spouses to seek marriage and family counseling services. Journal of Primary Prevention, 11, 277-293.

Brennan, K. A., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Attachment styles and personality disorders: Their connections to each other and to parental divorce, parental death, and perceptions of parental caregiving. Journal of personality, 66(5), 835-878.

Brussoni, M. J., Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. J., & Macbeth, T. M. (2000). Genetic and environmental influences on adult attachment styles. Personal Relationships, 7(3), 283-289.

Buehler, C. (1987). Initiator status and the divorce transition. Family Relations, 82-86.

Cherkas, L. F., Oelsner, E. C., Mak, Y. T., Valdes, A., & Spector, T. D. (2004). Genetic influences on female infidelity and number of sexual partners in humans: a linkage and association study of the role of the vasopressin receptor gene (AVPR1A). Twin Research and Human Genetics, 7(6), 649-658.

Cohen, O., & Finzi-Dottan, R. (2012). Reasons for divorce and mental health following the breakup. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 53(8), 581-601.

Cohen, P. N. (2019). The coming divorce decline. Socius, 5, 2378023119873497.

Copping, L. T., & Richardson, G. B. (2020). Studying sex differences in psychosocial life history indicators. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 6, 47-59.

Coşkun, S., & Sarlak, D. (2020). Reasons for Divorce in Turkey and the Characteristics of Divorced Families: A Retrospective Analysis. The Family Journal, 1066480720904025.

Cross, C. P., Copping, L. T., & Campbell, A. (2011). Sex differences in impulsivity: a meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin, 137(1), 97.

Damme, M. V. (2020). The negative female educational gradient of union dissolution: Towards an explanation in six European countries. In Divorce in Europe (pp. 93-122). Springer, Cham.

Deak, J. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2021). Genetics of substance use disorders: a review. Psychological medicine, 51(13), 2189-2200.

Del Giudice, M. (2019). Sex differences in attachment styles. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 1-5.

Doherty, W. J., Willoughby, B. J., & Peterson, B. (2011). Interest in marital reconciliation among divorcing parents. Family Court Review, 49(2), 313-321.

Doherty, W. J., Harris, S. M., & Wickel Didericksen, K. (2016). A typology of attitudes toward proceeding with divorce among parents in the divorce process. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 57(1), 1-11.

Doss, B. D., Atkins, D. C., & Christensen, A. (2003). Who’s dragging their feet? Husbands and wives seeking marital therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29(2), 165-177.

Dreznick, M. T. (2002). Sexual and emotional infidelity: A meta-analysis. State University of New York at Albany.

Eme, R. (2009). Male life-course persistent antisocial behavior: A review of neurodevelopmental factors. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(5), 348-358.

Eysenck, H. J. (1980). Personality, marital satisfaction, and divorce. Psychological Reports, 47(3_suppl), 1235-1238.

Felson, R. B., & Pare, P. P. (2007). Does the criminal justice system treat domestic violence and sexual assault offenders leniently?. Justice Quarterly, 24(3), 435-459.

Fetchenhauer, D., & Rohde, P. A. (2002). Evolutionary personality psychology and victimology: Sex differences in risk attitudes and short-term orientation and their relation to sex differences in victimizations. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23(4), 233-244.

Folke, O., & Rickne, J. (2020). All the single ladies: Job promotions and the durability of marriage. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12(1), 260-287.

Garcia, J. R., MacKillop, J., Aller, E. L., Merriwether, A. M., Wilson, D. S., & Lum, J. K. (2010). Associations between dopamine D4 receptor gene variation with both infidelity and sexual promiscuity. PloS one, 5(11), e14162.

Gottman, J. M., Coan, J., Carrere, S., & Swanson, C. (1998). Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 5-22.

Hald, G. M., Strizzi, J. M., Ciprić, A., & Sander, S. (2020). The divorce conflict scale. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 61(2), 83-104.

Hawkins, A. J., Willoughby, B. J., & Doherty, W. J. (2012). Reasons for divorce and openness to marital reconciliation. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 53(6), 453-463.

Hemez, P. (2017). Divorce rate in the US: Geographic variation, 2016. Family Profiles, FP-17, 24.

HI Rehim, M., KS Alshamsi, W., & Kaba, A. (2020). Perceptions of divorcees towards factors leading to divorce in UAE. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 61(8), 582-592.

Hyde, J. S. (1984). How large are gender differences in aggression? A developmental meta-analysis. Developmental psychology, 20(4), 722.

Idstad, M., Torvik, F. A., Borren, I., Rognmo, K., Røysamb, E., & Tambs, K. (2015). Mental distress predicts divorce over 16 years: the HUNT study. BMC public health, 15(1), 1-10.

Janus, S. S., & Janus, C. L. (1993). The Janus report on sexual behavior. John Wiley & Sons.

Jerskey, B. A., Panizzon, M. S., Jacobson, K. C., Neale, M. C., Grant, M. D., Schultz, M., … & Lyons, M. J. (2010). Marriage and divorce: A genetic perspective. Personality and individual differences, 49(5), 473-478.

Jocklin, V., McGue, M., & Lykken, D. T. (1996). Personality and divorce: a genetic analysis. Journal of personality and social psychology, 71(2), 288.

Kalmijn, M., De Graaf, P. M., & Poortman, A. R. (2004). Interactions between cultural and economic determinants of divorce in the Netherlands. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(1), 75-89.

Kalmijn, M., & Poortman, A. R. (2006). His or her divorce? The gendered nature of divorce and its determinants. European sociological review, 22(2), 201-214.

Kaplan, A., Endeweld, M., & Herbst-Debby, A. (2020). The more the merrier? The effect of children on divorce in a pronatalist society. In Divorce in Europe (pp. 123-143). Springer, Cham.

Kennedy, S., & Ruggles, S. (2014). Breaking up is hard to count: The rise of divorce in the United States, 1980–2010. Demography, 51(2), 587-598.

Killewald, A. (2016). Money, work, and marital stability: Assessing change in the gendered determinants of divorce. American Sociological Review, 81(4), 696-719.

Kim, D., & Oka, T. (2014). Divorce law reforms and divorce rates in the USA: an interactive fixed‐effects approach. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 29(2), 231-245.

Kitson, G. C., Babri, K. B., & Roach, M. J. (1985). Who divorces and why: A review. Journal of family issues, 6(3), 255-293.

Marín, R. A., Christensen, A., & Atkins, D. C. (2014). Infidelity and behavioral couple therapy: Relationship outcomes over 5 years following therapy. Couple and family psychology: Research and practice, 3(1), 1.

McGue, M., & Lykken, D. T. (1992). Genetic influence on risk of divorce. Psychological Science, 3(6), 368-373.

McNelis, M., & Segrin, C. (2019). Insecure attachment predicts history of divorce, marriage, and current relationship status. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 60(5), 404-417.

McNulty, Y. (2015). Till stress do us part: The causes and consequences of expatriate divorce. Journal of Global Mobility.

Osafo, J., Oppong Asante, K., Ampomah, C. A., & Osei-Tutu, A. (2021). Factors contributing to divorce in Ghana: an exploratory analysis of evidence from court suits. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 62(4), 312-326.

Parker, M. L., Diamond, R. M., Ledermann, T., & Tambling, R. R. (2022). The beginning of the end: A revised inventory of divorce initiation. Family Relations.

Previti, D., & Amato, P. R. (2004). Is infidelity a cause or a consequence of poor marital quality?. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21(2), 217-230.

Ponzetti Jr, J. J., Zvonkovic, A., Cate, R. M., & Huston, T. L. (1992). Reasons for divorce: A comparison between former partners. Journal of divorce & remarriage, 17(3-4), 183-201.

Putra, H. S., Anis, A., Azhar, Z., & Juneldi, J. (2021, November). The Phenomenon of Working Women with the Causes of Divorce. In Seventh Padang International Conference On Economics Education, Economics, Business and Management, Accounting and Entrepreneurship (PICEEBA 2021) (pp. 160-165). Atlantis Press.

Raley, R. K., & Sweeney, M. M. (2020). Divorce, repartnering, and stepfamilies: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 81-99.

Ralte, L. (2015). Divorce among women: A statistical analysis of the causes. Internatonal Journal in Management and Social Science. ISSN: 2321-1784, 3(07), 443-451.

Reynolds, L. (2020). Divorce rate in the U.S.: Geographic variation, 2019. Family Profiles, FP-20-25. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research. https://doi.org/10.25035/ncfmr/fp-20-25

Rodrigues, D., Lopes, D., & Pereira, M. (2017). Sociosexuality, commitment, sexual infidelity, and perceptions of infidelity: Data from the second love web site. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(2), 241-253.

Rotz, D. (2016). Why have divorce rates fallen?: The role of women’s age at marriage. Journal of Human Resources, 51(4), 961-1002.

Santos, C., & Weiss, D. (2012). Risky income, risky families: Marriage and divorce in a volatile labor market. Mimeo.

Sayehmiri, K., Kareem, K. I., Abdi, K., Dalvand, S., & Gheshlagh, R. G. (2020). The relationship between personality traits and marital satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC psychology, 8(1), 1-8.

Sayer, L. C., England, P., & Allison, P. (2005). Gains to marriage, relative resources, and divorce initiation. In annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Philadelphia.

Shadish, W. R., Ragsdale, K., Glaser, R. R., & Montgomery, L. M. (1995). The efficacy and effectiveness of marital and family therapy: A perspective from meta‐analysis. Journal of marital and Family Therapy, 21(4), 345-360.

Smoller, J. W., Andreassen, O. A., Edenberg, H. J., Faraone, S. V., Glatt, S. J., & Kendler, K. S. (2019). Psychiatric genetics and the structure of psychopathology. Molecular psychiatry, 24(3), 409-420.

Solomon, Brittany C., and Joshua J. Jackson. “Why do personality traits predict divorce? Multiple pathways through satisfaction.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 106.6 (2014): 978.

Stuart, G. L., McGeary, J. E., Shorey, R. C., Knopik, V. S., Beaucage, K., & Temple, J. R. (2014). Genetic associations with intimate partner violence in a sample of hazardous drinking men in batterer intervention programs. Violence Against Women, 20(4), 385-400.

Syamsiar, S., & Hasmawati, H. (2021, May). Causes of Divorce in Ternate City, North Maluku. In 2nd Annual Conference on Education and Social Science (ACCESS 2020) (pp. 145-148). Atlantis Press.

Tach, L. M., & Eads, A. (2015). Trends in the economic consequences of marital and cohabitation dissolution in the United States. Demography, 52(2), 401-432.

Thöni, C., & Volk, S. (2021). Converging evidence for greater male variability in time, risk, and social preferences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(23), e2026112118.

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, Maryland: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality.

Vasudevan, B., Geetha, D. M., Bhaskar, A., Areekal, B., & Lucas, A. (2015). Causes of divorce: a descriptive study from Central Kerala. Journal of evolution of medical and dental sciences, 4(20), 3418-3427.

Vaterlaus, J. M., Skogrand, L., & Chaney, C. (2015). Help-seeking for marital problems: Perceptions of individuals in strong African American marriages. Contemporary Family Therapy, 37, 22-32.

Wang, H., & Amato, P. R. (2000). Predictors of divorce adjustment: Stressors, resources, and definitions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(3), 655-668.

Weiss, B., Lavner, J. A., & Miller, J. D. (2018). Self-and partner-reported psychopathic traits’ relations with couples’ communication, marital satisfaction trajectories, and divorce in a longitudinal sample. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 9(3), 239.

Weisberg, Y. J., DeYoung, C. G., & Hirsh, J. B. (2011). Gender differences in personality across the ten aspects of the Big Five. Frontiers in psychology, 178.

Whitaker, D. J., Haileyesus, T., Swahn, M., & Saltzman, L. S. (2007). Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. American journal of public health, 97(5), 941-947.

Zietsch, B. P., Westberg, L., Santtila, P., & Jern, P. (2015). Genetic analysis of human extrapair mating: heritability, between-sex correlation, and receptor genes for vasopressin and oxytocin. Evolution and Human Behavior, 36(2), 130-136.

3 comments

Just a few points that I disagree with in Alex’s conclusion:

1) “Fewer than 10% of divorced couples receive alimony”. This statistic is a myth. For example, in my divorce and most others, I gave up a higher % of my money and assets (70%) in order to get rid of the obligation to pay alimony. So, technically and legally, my divorce, like most others, does not involve alimony even though I actually paid it by surrendering a larger % of my money and assets upfront. Although, to be fair to Alex, I wouldn’t expect him to understand this point as he is not a family lawyer and it seems like he has never actually experienced divorce.

2) “Choose a partner wisely”. This is quite a vague statement. What does “wisely” mean? Do you vet your partner for 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, 5 years, 10 years? Do you live with them beforehand? What happens if your nice, sweet, slim, happy and childless 25 year old partner, changes after 10 years of marriage, 10 years of weigh gain, 10 years of boredom, 2 kids, 2 bouts of post-natal depression, etc. I don’t agree with the myth that men can “choose a partner wisely” and predict with any accuracy how their 50 year marriage will work out. If a husband thinks he is able to predict with accuracy how his 50 year marriage will work out I believe he is seriously deluded.

3) “Big cash windfall” and “monthly child support of $300”. While most divorces probably don’t result in a “big cash windfall”, if the man does acquire assets during the marriage a divorce will result in a windfall. In other words, there is nothing for the wife to lose by getting married. If her and her husband are broke, they will stay broke after divorce, i.e. she lost nothing by getting married. However, if her husband becomes rich, she will gain a windfall. In other words, its win-win for the wife, especially if all she wants kids and grandkids (rather than money).

It has been a while since I read this but it does make me think about how lesbian have double the divorce rate of gay male relationships.

Here’s a feminist’s view on why: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/what-explains-the-rise-in-lesbian-divorce/

But this seems counter intuitive with men having a lot of traits that I would associate with relationships failing