Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

How do you study sexual behavior in human beings? You can’t install cameras in a bedroom. You can’t follow everyone around with a drone. You can use penile plethysmography, pupil dilation, or skin conductance if you want to measure physical arousal to erotic stimuli, but this may not be suited to the questions you want to ask. At the end of the day you’re stuck with having to ask people.

This raises questions like, “don’t people lie?” In psychology this is related to what is called social desirability bias. I have written about social desirability bias in the past (and why sexual behavior surveys are mostly accurate), so I won’t redo the literature review. You can read it here: Is Self Reported Sexual Partner Data Accurate?

Instead, in this article I will share my results from an attempted replication of a recent paper looking at social desirability bias in self-reports of oral sex.

The Clerks Effect: Did She Give 37 Blowjobs?

A popular narrative is that that women have more sexual partners than they report, but underreport sexual partners because they don’t count all sexual acts. The movie Clerks plays on this: in a dialogue with the protagonist, the protagonist’s girlfriend claims she has had three sexual partners but has given thirty-seven blowjobs. How true to life is the perspective that oral sex doesn’t really count?

There is some evidence that it could be the case. A recent YouGov survey (2023) found slightly less than half of respondents said they counted oral sex as “having sex.” Similar figures were found for other sexual acts that were not penis-in-vagina (PIV) sex. Does this mean we’re systematically underestimating the number of sexual partners in our surveys?

This may depend on the survey. Many, such as the General Social Survey (GSS), are more specific with their questions. If you ask “how many people have you had sex with,” “how many sexual intercourse partners have you had,” or “have you had sexual contact, including oral-to-genital contact” you may receive different answers.

This question has also made its way into the scientific literature. Most of the research on social desirability bias is old and likely overestimates the effect. It was conducted decades ago when surveys were given in person, which we know enhances the effect of social desirability bias. Now we have anonymous surveys online. We know some other tricks to mitigate social desirability bias, too.

Recently, I was searching for new literature on social desirability bias in sexual self-report surveys. I found a paper entitled “Oral-Genital Contact and the Meaning of “Had Sex”: The Role of Social Desirability” (Den Haese & King, 2022). Jackpot. I found something new.

Results from Den Haese and King

Den Haese and King (2022) wanted to find out if people who reported having oral sex did not report that they “had sex.” In other words, did oral sex not count for some people? To these ends, they collected a sample of 847 men and women with a mean age of 19. They reported that two-thirds of the initial sample consisted of women. 73% of the sample reported that they “had sex.” 65 women and 12 men reported that they did not “have sex,” but that they did engage in oral-genital contact.

In other words, about 11% of sexually active young women did not count the oral sex they had as “having sex.” They were oral sex virgins.

Den Haese and King (2022) also employed the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960). This is a true/false scale that asks questions indicating a disposition toward social desirability bias. If you respond affirmatively to socially desirable items, many of which are implausible yet stigmatized to deny, you get a larger score. This gives you a way to measure an individual tendency toward social desirability bias.

Did social desirability bias predict reporting having oral sex, but not having “had sex?” It did. The effect was large with a Hedge’s g of .78. Further, there was a sex difference, with women being more likely to be in the “had oral sex but didn’t have sex” category. The sex difference was small with a phi of .23.

We have some evidence that those who are more affected by social desirability bias may report oral sex as not “having sex.” Further, these results indicate that a minority of young women really do this.

Can I Replicate Den Haese and King?

I collected a convenience sample of 628 participants (181 female). The sample consisted of 109 heterosexual women and 399 heterosexual men. 153 women reported having had sex and 334 men reported having had sex. Of these, 61 women and 134 men were aged 25 or below.

I followed the procedure outlined in Den Haese and King (2022). Spaced evenly throughout the Marlowe-Crowne scale were the same four sexual behavior questions used in the original experiment.

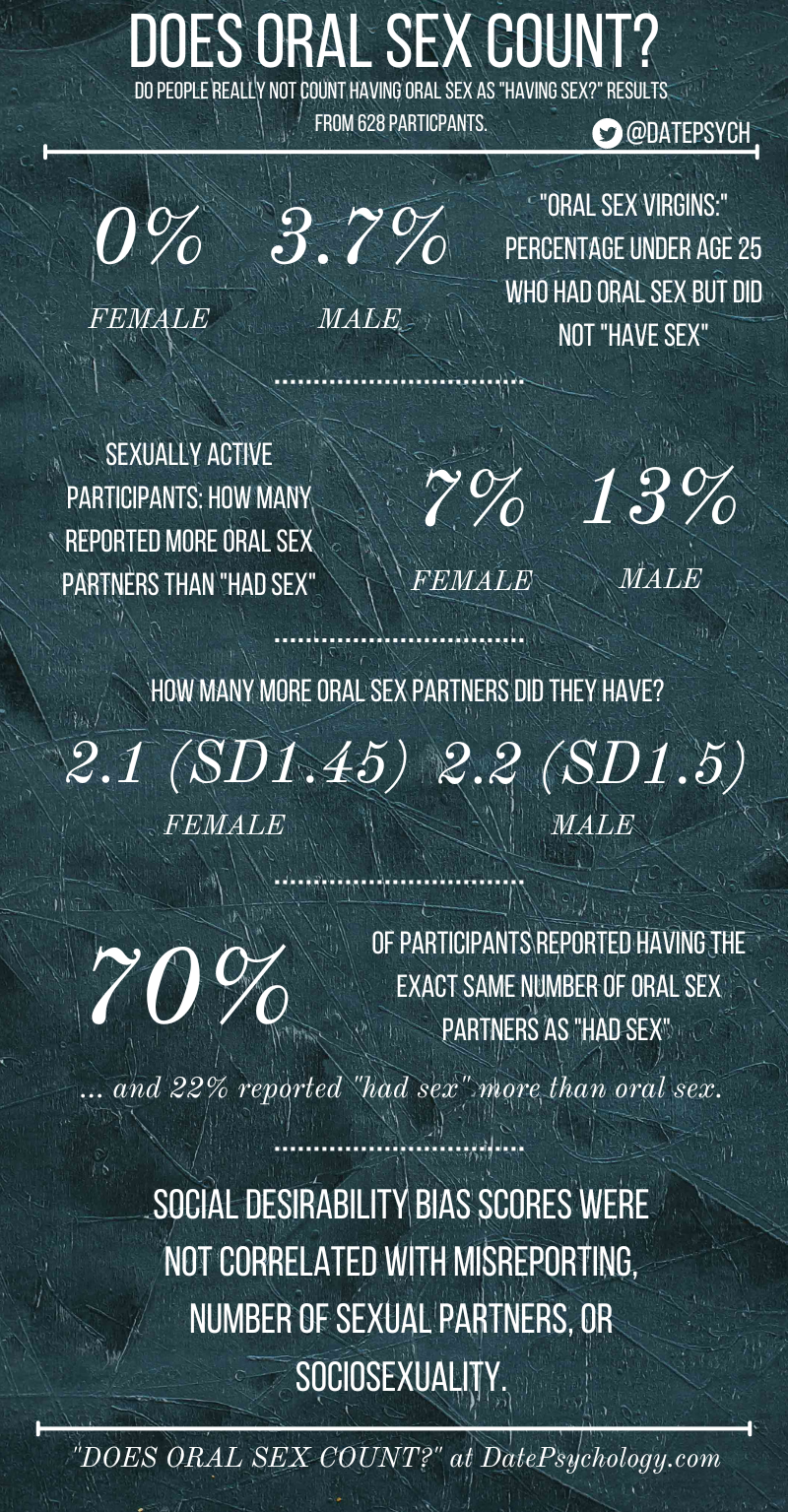

In my sample, what percentage of young women fell into the “No-Yes” category, or the women who reported having had oral sex but not having “had sex?” It was 0%. Not one woman reported that she had oral sex but did not “have sex.” Five men fell into the “No-Yes” category, or reported having had oral sex, but that they did not “have sex.”

I was not able to replicate a similar percentage of women who didn’t count oral sex as “having sex.” Given that my “No-Yes” groups were zero and four, the replication stopped there. I couldn’t test if “No-Yes” women scored higher in social desirability because they didn’t even exist in my data.

We may also ask: did women report they “had sex” if they indicated that they did not have PIV sex, but did have oral sex? Seven women reported that they “had sex” and had oral sex, but not PIV sex. These seven women also indicated they were bisexual or gay/lesbian.

Testing The Clerks Effect

I anticipated a small subsample of young participants based on demographics from past survey recruitment. I still wanted to test the Clerks phenomenon. Further, the Den Haese and King (2022) methodology left some questions unanswered. To these ends I asked participants to report the number of people they “had sex” with and the number of people they had oral sex with (again using the terminology in Den Haese & King, 2022).

140 participants (47 women) reported more “had sex” partners than oral sex partners. 57 participants (12 women) reported more oral sex partners than “had sex” partners. Meanwhile, 443 participants, 70.5% of the sample, reported having exactly the same number of “had sex” and oral sex partners.

It looks like it’s actually rare for people not to count oral sex as having “had sex.” In women, 6.6% of the sample had more oral sex partners than “had sex.” In men, it was 12.7%. Contrary to popular discourse, men were more likely than women not to count oral sex as having “had sex.”

This raises another question: is anyone pulling a Clerks and claiming they have only had three sexual partners despite having given thirty-seven blowjobs? So far, we have only looked at what percentage misreports up or down. But by what magnitude did participants misreport?

Across participants who reported more oral sex than “had sex,” the mean difference was 2.12 oral sex partners with a standard deviation of 1.45 and a range of 1 to 8. For women, the average was 2.1 with a standard deviation of 1.45 and a range of 1 to 3. For men, the average was 2.2 with a standard deviation of 1.5 and a range of 1 to 8. No real sex difference. We don’t see massively underreported “had sex” numbers. We don’t see substantially larger numbers of oral sex partners. Clerks was fiction.

Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scores

At this point, I had a group that didn’t count all of their oral sex as “having sex.” With this I could test if misreporting is driven by social desirability bias in line with the findings of Den Haese and King (2022). A t-test indicated the difference between participants who reported more oral sex than “had sex” and participants who did not was not statistically significant (p = 0.0794). The mean social desirability score for the group that reported more oral sex than “had sex” was 13.93 and the mean for the participants who did not was 15.27. In other words, although not significant, the direction of the effect was not even what you might expect. The participants who didn’t report more oral sex partners had a higher average social desirability score.

It looks like we can’t attribute participants reporting more oral sex partners than “had sex” partners to social desirability bias.

What about simply reporting fewer partners in general? That’s the general idea, after all: social desirability bias drives women to underreport the number of past sexual partners that they have had. A Pearson’s correlation between the number of sex partners and social desirability scores was not statistically significant (r = -0.02, p = 0.547). Participants higher in social desirability bias did not report they “had sex” with fewer people. Additionally, there was no relationship between social desirability scores and self-reported number of oral sex partners (r = -0.01, p = 0.782). Not only was the relationship not significant, but the correlation coefficient (denoted by r) was close to zero.

For men, the relationship between the number of “had sex” partners and social desirability scores was not significant (r = 0.01, p = 0.832) and the relationship between the number of oral sex partners and social desirability was not significant (r = 0.02, p = 0.633). For women, the relationship between the number of “had sex” partners and social desirability scores was not significant (r = -0.11, p = 0.154) and was also not significant for the number of oral sex partners (r = -0.1, p = 0.162).

Was there even a sex difference in social desirability bias? A t-test indicated no (p = 0.074). The mean social desirability bias score for men was 15.39 and for women was 14.58.

Sociosexuality and Social Desirability Bias

I used the sociosexuality inventory (SOI-R) of Penke and Asendorpf (2008). This contains items that ask about sexual behaviors, attitudes, and desires. Given what this inventory asks, we might also expect social desirability bias to impact honest reporting. Is it so? Not for men (r = -0.04, p = 0.355) nor for women (r = -0.05, p = 0.515).

Does the SOI-R predict sexual behavior for men and women? For men, SOI-R scores predicted “had sex” (r = .46, p < 2.2e-16) oral sex (r = .45, p < 2.2e-16), and anal sex (r = .25, p = 5.143e-08) partners. For women, SOI-R scores predicted “had sex” (r = .37, p = 2.776e-07), oral sex (r = .37, p = 3.599e-07), and anal sex (r = .28, p = 0.0001) partners. In other words, the SOI-R predicts sexual behavior well, but has no relationship with social desirability.

Age, Past Sexual Partner Count, and Misreporting

Are the young or the old more likely to not report oral sex as “having sex?” I found no statistically significant age difference between groups (p = 0.294 women; p = 0.297 men). The mean age of women who reported fewer “had sex” partners was 34 and the mean age of women who did not was 31. The mean age of men who reported fewer “had sex” partners was 31 and for men who did not was 33.

Past sexual partner count was also not associated with being in the group that reported fewer “had sex” partners than oral sex partners (p = 0.373 women; p = 0.181 men). The mean numbers of past sexual partners for both groups of women were 5.5 and 7.2, while for men were 5.6 and 6.8.

Age was also unrelated to social desirability bias for women (r = 0.04, p = 0.553) and for men (r = -0.04, p = 0.394).

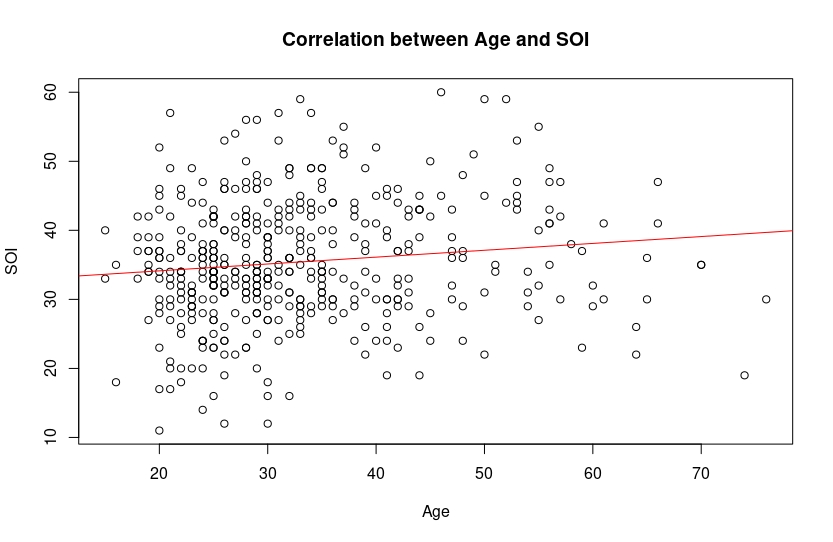

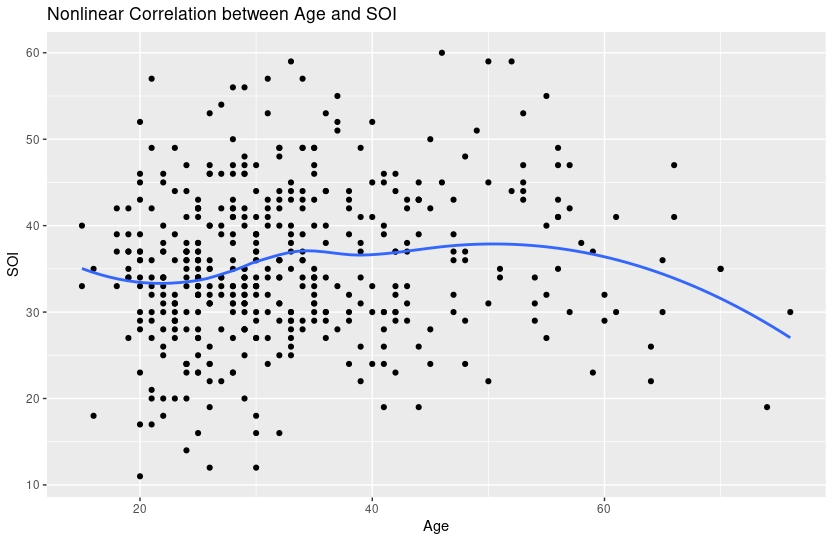

Age did not predict sociosexuality for women (r = 0.09, p = 0.22), but age did have a small positive correlation with sociosexuality for men (r = 0.13, p = 0.007). In other words, older men scored slightly higher in sociosexuality. It doesn’t look like a real linear relationship however. You can see SOI-R scores decline for older men:

A positive correlation was found for age and number of sexual partners for women (r = 0.43, p = 1.669e-09) and for men (r = 0.47, p < 2.2e-16). Unsurprisingly, as people get older they accumulate more sexual partners. The regression coefficient for men was 0.32 and for women was 0.33. In other words, for every additional year on average the number of sexual partners increases by .33.

What’s the takeaway from this section — are younger participants more likely to misreport oral sex as not “having sex?” It doesn’t look like it. They don’t score differently in social desirability bias, nor do they score higher in sociosexuality. They don’t seem to be outpacing older individuals in accumulating sexual partners.

The Redpilled and the Blackpilled

I asked survey participants if they were “redpilled” or “blackpilled.” The mean number of sexual partners for men who said they were redpilled was 6.3 and for men who said they were not redpilled was 6.9. This difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.493). However, men who said they were redpilled indicated a higher sociosexuality (p = 0.013). The mean for men who identified as redpilled was 37.13 and for men who did not was 34.83. There was no difference in social desirability scores between groups (p = 0.529).

There was a significant difference in the number of sexual partners for men who identified as blackpilled versus those who did not (p = 0.006). Men who said they were blackpilled had an average of 4.2 sexual partners and men who said they were not had an average of 7. There was no significant difference in sociosexuality between men who said they were blackpilled and men who were not (p = 0.431), nor was there a significant difference in social desirability bias (p = 0.338).

Discussion

Let’s recap: a recent YouGov survey (2023) asked people “does oral sex count.” About half said no. Another recent paper found approximately 11% of young women (mean age 19) reported they had oral-genital contact, but that they did not “have sex” (Den Haese and King, 2022). My results are a bit different. I didn’t find any young women who reported having oral sex but not having had sex. Additionally, I found very few women across all age groups who reported more oral sex partners than “had sex” partners. I found about twice as many men who did. Further, of participants who did report more oral sex partners, the difference was small: about 2 people on average for both men and women. Additionally, I found no sex difference in social desirability scores.

Why did I get different results? We know a lot of research in psychology (and all fields that study human beings) simply does not replicate. This doesn’t imply anything bad about the researchers. Journals incentivize the publication of significant results, not null results (here I can share any result I get). We don’t know how many unpublished null results are floating around in the “file drawers” of the universities.

What about the YouGov survey? Well, if you ask someone “does oral sex count” you’re asking a completely different question. You’re not measuring if participants count their own oral sex as “having sex.” They might very well think “it isn’t technically sex, because it isn’t PIV sexual intercourse,” but still report “had sex” on a form because they understand what is being asked.

Further, researcher heterogeneity in methodology can lead to nonreplication. Even when you give researchers the exact same datasets they may produce different results (Open Science Collaboration, 2015). I didn’t use the same dataset nor did I only ask the same questions.

Related to this, the population that the sample was drawn from was also different. Den Haese & King (2022) drew from a population of students at Clemson University in South Carolina. I drew from an online sample. This does not mean one sample is better or worse; both are nonrepresentative convenience samples (see: Twitter Convenience Samples). However, they do reflect different populations.

That said, differences across populations are not the best explanation for the inability of the Marlowe-Crowne scale to predict sexual behavior or the under-reporting of “had sex” partners. We make assumptions about a quasi-universality of human psychology. We assume social desirability bias is a general feature of human behavior. We also tend to assume that relationships between psychological variables should apply to most people across populations. This is why we continue to use convenience samples, be it from an online platform or from a convenience sample of WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) students. It’s not an entirely warranted assumption, but it really does tend to work, which is why we keep doing it.

A better explanation may be the modifications I made to the methodology when I administered my survey. Unmentioned in the methods above, I requested that participants answer honestly and I reminded them that the survey was anonymous. It may sound too good to be true, but we know from past research that this does reduce social desirability bias in surveys (Fisher, 1993; Grimm, 2010; Larson, 2019). Further, this was a survey online. Den Haese & King (2022) administered a pencil-and-paper survey. This was probably in a lab or in a classroom setting. That will generate socially desirable reporting. If you can avoid making someone come into the lab, or if you can avoid making them fill out a questionnaire in front of you, then you will get more honest results.

This effect can be seen in two papers by Alexander and Fischer (2003; Fisher, 2013). They used a method called the “bogus pipeline.” It is a fake polygraph or lie detector. It doesn’t matter if it can really detect lies. The idea is that participants who believe they will be caught report more honestly. The effect works. However, the results of this specific research are often misreported. Participants did report having more sexual partners when connected to the polygraph, but only when compared with the non-anonymous condition. Anonymous surveys generated honesty to the same extent that the bogus pipeline condition did. Further, the difference in sexual partners reported across all conditions was small (about 1 to 1.5 additional partners under the bogus pipeline).

What’s the real truth around social desirability bias in 2023? In the context of sexual self-reports, at least, it’s probably low. Recent research has indicated that Sexual Double Standards (SDS) are fading away, in particular when it comes to one’s own sexual behavior (Stewart-Williams et al., 2017). We live in a period of extreme sexual permissiveness (which does not mean that people usually act on it). Unasked and unprompted, men and women who do take liberty of Western culture’s sexual permissiveness regularly share their intimate sexual histories on social media, YouTube, and TikTok to the entire world.

There are individuals within the broad dating discourse spinning tales and (literally) selling promiscuity narratives. They would like for you to believe them, the guru, and not the statistics. They will practically beg you: “please don’t listen to the statistics bro.” They just know everyone is engaged in extreme promiscuity. They know the shy Girl Next Door has secretly had sex with the dog, cat, mailman, and the entire football team. They can’t prove it, because it’s a secret, but “it is known.” It feels right to them.

Is it naive not to believe them? It’s probably more naive to believe that women who are willing to be highly promiscuous are afraid of reporting it on an anonymous survey. It’s an internalized Madonna/whore dichotomy, or an internalized “blue pill.” It’s the belief that the most sexually unrestricted people are truly, deep inside, quite restricted.

The men telling you these stories are not better with women and don’t have more sexual experience to draw from, by the way. In the current results we saw that “redpilled” men do not have more sexual partners than men who are not. “Blackpilled” men have fewer. This is consistent with past research of mine that found no higher, and often lower, sexual success, relationship satisfaction, and higher sexlessness across manosphere groups (see: Theory of mind, hostile attribution bias, and incels). In the current results, not only did “redpilled” men not have more sexual partners, but they also scored higher in sociosexuality — indicating a higher desire for casual partners. That they have a higher desire for casual sex partners, but don’t have correspondingly more sexual partners (as SOI scores usually predict), may even indicate that they do a little worse with women relative to their own motivation.

Redpill and blackpill identifying men also did not score differently in social desirability bias themselves. This is important if your mental model of the world is “everybody is lying and unaware (except for me, I am honest and highly self-aware).” Additionally, there was no sex difference in social desirability scores. The results don’t support women being more susceptible to social desirability bias. What the results may indicate is that “redpilled” men are not quite as redpilled as they believe. If you look at the items on the Marlowe-Crowne scale, not only do they require the willingness to admit flaws in oneself, but they also require the ability to recognize flaws in oneself in the first place. You might expect people who claim to have awoken to the “uncomfortable truths” about human nature to have lower social desirability scores, but they did not.

References

Alexander, M. G., & Fisher, T. D. (2003). Truth and consequences: Using the bogus pipeline to examine sex differences in self‐reported sexuality. Journal of sex research, 40(1), 27-35.

Den Haese, J., & King, B. M. (2022). Oral-genital contact and the meaning of “had sex”: The role of social desirability. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(3), 1503-1508.

Fisher, R. J. (1993). Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal of consumer research, 20(2), 303-315.

Fisher, T. D. (2013). Gender roles and pressure to be truthful: The bogus pipeline modifies gender differences in sexual but not non-sexual behavior. Sex Roles, 68(7-8), 401-414.

Grimm, P. (2010). Social desirability bias. Wiley international encyclopedia of marketing.

Larson, R. B. (2019). Controlling social desirability bias. International Journal of Market Research, 61(5), 534-547.

Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), aac4716.

Penke, L., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2008). Beyond global sociosexual orientations: A more

differentiated look at sociosexuality and its effects on courtship and romantic relationships.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1113-1135

Stewart-Williams, S., Butler, C. A., & Thomas, A. G. (2017). Sexual history and present attractiveness: People want a mate with a bit of a past, but not too much. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(9), 1097-1105.

YouGov, 2023. “Does oral sex count as “having sex”?”