Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

Theory of mind is the cognitive ability to infer the mental states of another person (Ballesteros & Ibanez, 2021). When I first learned about theory of mind my initial thought was how critical of an ability this must be for relationships. Indeed, theory of mind is a part of what cognitive psychology and neuroscience calls social cognition. Yet, surprisingly little research has been done on theory of mind and relationships.

What we do know about theory of mind is that it is a highly implicated deficit in autism. Yirmiya et al. (1998) called theory of mind the “core deficit of autism.” Neurologically, theory of mind deficits are also associated with frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (Bora et al., 2015) as well as lesions in the temporal lobe, prefrontal cortex, posterior parietal cortex, and temporo-parietal junction (Bomfim et al., 2021). Deficits in theory of mind impair one’s ability to recognize emotion (Mitchell & Phillips, 2015). Activation in brain regions associated with theory of mind predict partner well-being in relationships (Dodell-Feder et al., 2016) and understanding one’s partner’s mental states (Esménio et al., 2019).

Incels, or involuntary celibates, are a community of men who struggle to form romantic and sexual relationships with women. Past research has found that incels self-report autism and have a rate of formal diagnosis twice as high as the general population (Moskalenko et al., 2022 1; Moskalenko et al., 2022 2; Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2022). Given the overlap between autism and theory of mind deficits, we might suspect theory of mind deficits in incels as well.

Hostile attribution bias refers to the cognitive tendency to attribute hostile actions toward others when the behavior of others is benign or ambiguous.

In my own interactions with incels I have noticed they have a tendency to describe interactions with women as hostile. For example, an incel might relate an experience such as: “women often look at me as if I am disgusting and they hate me.” If incels are physically unattractive (a common belief incels hold of themselves) this might reflect an accurate perception. People may experience discrimination and adverse treatment due to low physical attractiveness (Cavico et al., 2012).

However, it may also be the case that treatment is ambiguous or neutral, yet perceived as hostile — hostile attribution bias at work. Nisbett & Wilson (1977) identified the Halo Effect: an unconscious bias where we perceive and treat physically attractive individuals more positively. A reverse effect is less clear (although I suspect it also exists; see “lookism” and attractiveness discrimination).

What may be more common is that less attractive people are ignored, rather than being treated in an explicitly negative way. A man who has been ignored by women his entire life may frame it as being treated badly, when in fact he has not been treated at all. Neutral interactions (or lack thereof) with women may be interpreted as hostile.

To my knowledge, no research has been conducted on theory of mind or hostile attribution bias in incels. In fact, the literature on sex and relationships in respect to theory of mind and hostile attribution bias is quite sparse. Both reflect a potential to misunderstand a partner and both reflect deficits that may prevent the formation of close romantic or sexual relationships.

In this article I will present short original research and preliminary evidence on hostile attribution bias, theory of mind, and sexual/relationship outcomes for incels, a few other “manosphere” groups, and individuals outside of these populations.

Methodology

Incels

Much literature on incels approaches them as misogynists and extremists. Aside from being a stigmatizing approach, this is limited in what it can tell us about the psychological bases for inceldom.

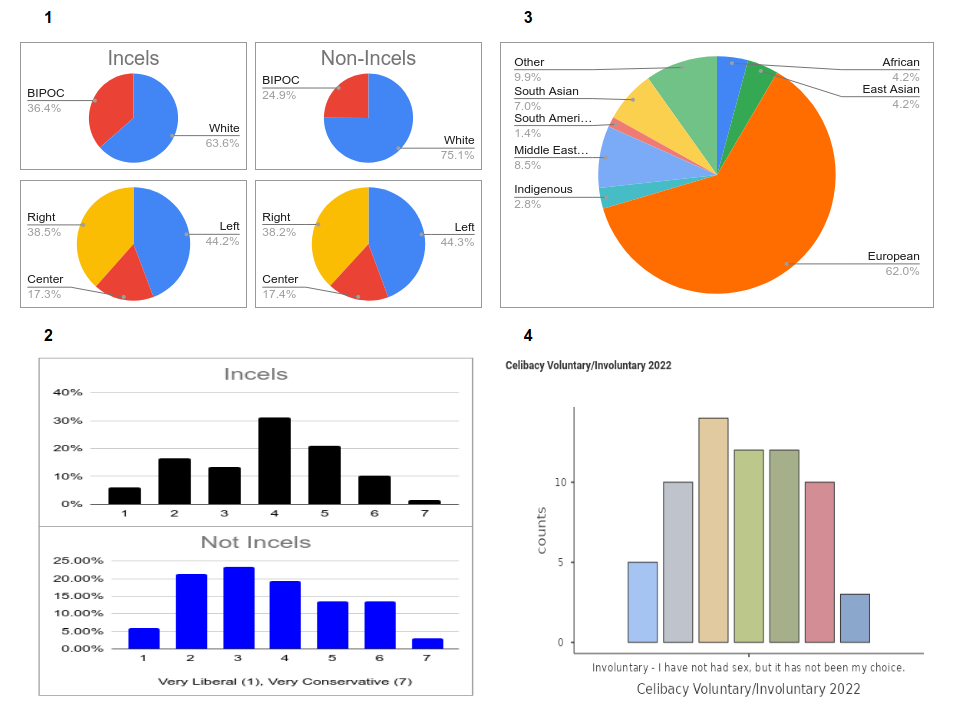

More recently, psychologists have begun to empirically examine the psychological underpinnings of inceldom. Costello et al. (2022) found that incels have high depression, anxiety, and loneliness, as well as lower life satisfaction. Sparks et al. (2023) similarly found high depression and anxiety, low self-esteem, higher avoidant attachment, and lower secure attachment. Further, incels may not be homogeneously White, nor right-wing, as they are often depicted to be in the popular media. (Figure 1.)

Incel may also be operationalized differently across the literature. For example, Scaptura & Boyle (2020) developed an “incel trait” scale on a sample of heterosexual men who may not be incels at all. In this case, incel is used as a proxy for misogynist, which is how it is often used colloquially. Additionally, incel may mean membership or participation in an incel community (such as when samples are drawn from incel forums). Incel may also mean someone who is involuntarily celibate in a literal sense. They may not identify as incels, nor participate in incel communities, but nonetheless be unable to form sexual or romantic relationships.

Here I have operationalized incel to address these differences across questions.

Items on literal involuntary celibacy; I asked “are you involuntarily celibate” and “are you involuntarily single.”

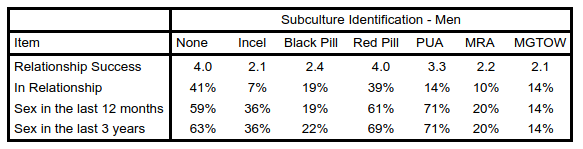

Item on incel subculture identification; I asked “have you identified with the following subcultures or communities.” Potential responses included none, incels, Red Pill, Black Pill, MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way), MRA (Men’s Rights Activists), PUA (Pick-Up Artists), and FDS (Female Dating Strategy; a female community sometimes compared with the aforementioned groups).

Items on recent sexual behavior; I asked “have you had sex within the past 12 months” and “have you had sex within the past 3 years.” This gives a measure of short to medium term celibacy. I also asked “are you in a committed relationship” and “have you experienced a break-up in the past 12 months.”

Finally, I asked about self-perceived relationship success with the item: “How successful have your romantic relationships been with the sex or gender you are attracted to?”

Theory Of Mind

As a measure of theory of mind, I used the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET) (Baron-Cohen, 2001). I randomly selected 25 out of a potential 36 items from the RMET to keep the questionnaire short. This test involves accurately assessing an emotional expression from a cutout of eyes.

Hostile Attribution Bias

To measure hostile attribution bias, I used items from the Social Information Processing–Attribution Bias Questionnaire (SIP–ABQ) (Coccaro, 2009). For this I selected only items intended to measure hostile attribution in order to keep the questionnaire short. This scale uses vignettes of negative, but ambiguously intentioned, scenarios and asks participants to rate the intention of the protagonists in the vignettes.

Statistics

Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with the wilcox.test function in R, regression with the lm function in R. I report effects as Cohen’s d; effect size estimates were similar for Hedges’ g and Glass’ Delta. R² reported throughout is adjusted R².

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Participants were 108 female (mean age 31.8, SD 10.9), 225 male (mean age 32.7, SD 10.9), and 5 other (mean age 29.6, SD 12.9) (total N = 338). 87.8% of participants reported as heterosexual, 8.7% as bisexual, 2.4% as gay or lesbian, and 1.1% as other. 79.3% reported as not belonging to any manosphere communities given as options.

Hostile Attribution and RMET

Hostile attribution did not predict RMET scores (R² = -0.000, F(1, 366) = 0.827, p = 0.364).

Main Analysis – RMET and Hostile Attribution

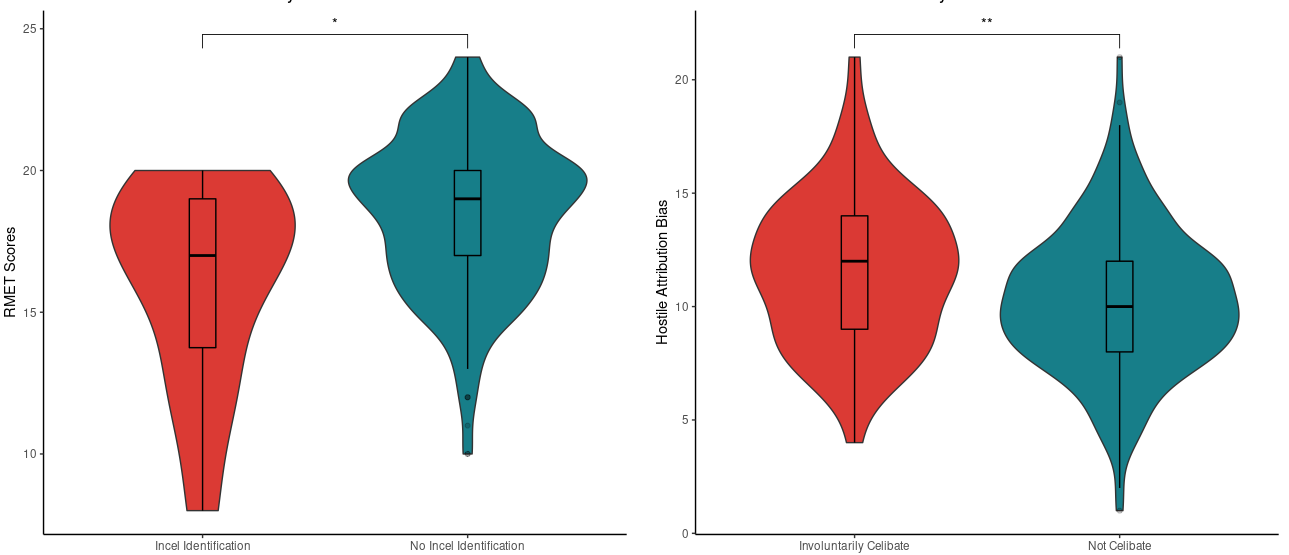

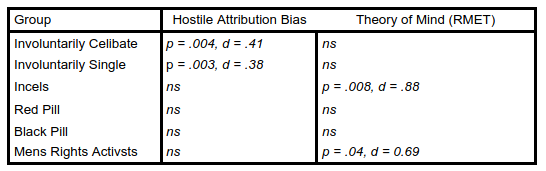

Incel subculture identification was associated with lower scores on the RMET (p = .008, d = .88), but not higher hostile attribution bias (p = 0.159). However, identifying as “involuntarily celibate” was associated with higher hostile attribution bias (p = 0.004, d = .41), but not lower RMET scores (p = 0.344). (Figure 1, Table 1.) “Involuntarily single” was not associated with RMET scores (p = 0.679), but was associated with higher hostile attribution (p = 0.003, d = .38).

The Spearman’s correlation coefficient for incels and involuntarily celibate was .22, while for incels and involuntarily single it was .16, indicating low overlap between the two types of responses. Only 21% of participants who reported as “involuntarily celibate” also reported identifying with the incel subculture or community. Involuntarily single and involuntarily celibate correlated at .66 and showed similar outcomes for RMET scores and hostile attribution bias. Black Pill subculture identification correlated with involuntary celibate at .29, involuntarily single at .23, and incel subculture identification at .46.

Age, The Mating Crisis, RMET, and Hostile Attribution

The term “mating crisis” has been used to describe the large number of young single men, particularly pronounced in the 18-25 age demographic. However, no difference was detected in RMET (p = 0.895) or hostile attribution (p = 0.203) for men between 18-25 and for the older group of remaining men in my sample.

Incel Subanalysis

In the data I found that approximately 40% of people who identified with the incel subculture reported having had sex either within the past 12 months or 3 years. (Table 2.) Within the incel subculture, the term “fakecel” is used to describe members who are able to form relationships or have sex. I removed these datapoints and redid the analysis for individuals who identified with the incel subculture but indicated they did not: have sex within the past 12 months or 3 years, and who indicated they were not in a relationship. I compared this group with men who reported not identifying with any of the “manosphere” subcultures listed.

RMET scores, but not hostile attribution bias, remained associated with incel subculture identification (p = 0.037, d = .86, and p = 0.348 respectively).

To rule out men who might be functional incels, but who neither report as involuntarily celibate nor who identify with the incel subculture, I compared men who had sex within the past 3 years with those who have not. I found no difference between groups for RMET scores (p = 0.864 or hostile attribution bias (p = 0.102).

Manosphere Subanalysis

There were only enough responses to do a meaningful analysis for Red Pill, Black Pill, and MRA. Only MRA was associated with lower RMET scores (p = 0.042, d = .8). Red Pill, Black Pill, and MRA were not associated with hostile attribution bias over the comparison group of men who reported no subcultural identification. Red Pill and Black Pill were also not associated with lower RMET scores.

Sexual Activity, RMET, and Hostile Attribution

Hostile attribution bias and theory of mind deficits might negatively impact relationship outcomes. A regression analysis found a relationship between hostile attribution and not having had sex within the last 12 months (R² = 0.019, F(1, 366) = 7.092, p = 0.008) and within the last 3 years (R² = 0.017, F(1, 366) = 6.359, p = 0.012) across the whole sample.

There was no relationship between RMET scores and sex in the last 12 months or the last 3 years. There was also no relationship between RMET or hostile attribution and having experienced a breakup in the last 12 months, nor a relationship between RMET or hostile attribution and being in a romantic relationship.

RMET, Hostile Attribution, and Self-Reported Relationship Success

Women self-reported significantly higher relationship success than men (p < .001, d = .43). The mean scores on a 7-point Likert scale for men were 3.77 (SD 1.98) and for women 4.6 (SD 1.76). This difference remained significant when removing incels and manosphere groups (p = 0.011, d = .34, M Male 3.97, SD Male .34).

Hostile attribution, but not RMET scores, predicted lower self-reported relationship success for the full sample (R² = 0.037, F(1, 366) = 15.02, p < 0.001). Neither hostile attribution nor RMET scores predicted self-reported relationship success for men. RMET did not predict self-reported relationship success for women, but hostile attribution did predict lower self-reported relationship success (R² = 0.038, F(1, 106) = 5.177, p = 0.025).

Gender Subanalysis

68% of women and 60% of men reported having had sex within the past 3 years, while 60% of women and 55% of men reported having had sex within the past year. These differences were not statistically significant ((X² = 3.2466, df = 1, p = .072 and X² = 0.6284, df = 1, p = .428 respectively). Women scored higher on the RMET than men (p = 0.014, d = .30) but no difference was detected between men and women for hostile attribution.

Women who did not have sex within the past 3 years or the past 12 months did not score differently on the RMET or in hostile attribution than men who had sex within the past 3 years or past 12 months. Additionally, women who did not have sex within the past 3 years or 12 months did not score differently on the RMET or in hostile attribution from women who had sex within these time frames.

Discussion

Hostile attribution and theory of mind don’t seem to be directly related in these results. While both represent a way that people may come to misunderstand others, the mechanism and expression behind the two may be different. There is nothing implicitly inherent in misreading the emotions of others that implies you will misread them in a hostile way.

Hostile attribution also predicts relationship and sexual outcomes differently from theory of mind in these results. Hostile attribution was associated with being involuntarily celibate and involuntarily single, but not as identifying with the incel subculture. Additionally, hostile attribution predicted not having had sex within the past 12 months and the past 3 years. Hostile attribution also predicted lower self-reported relationship success, in particular for women.

On the other hand, theory of mind, as estimated by the RMET measure, was associated only with incel subculture identification and MRA subculture identification. It did not predict relationship or sexual outcomes for any group. This would be consistent with past research that has found high rates of self-reported and diagnosed autism in incel communities. Some of you who read this will have taken this test — keep in mind that it cannot diagnose autism.

Correlations between self-reported involuntarily celibates and incel subculture identification were low. It is worth considering that when studying the phenomenon of being involuntarily celibate, or when studying incel communities, the two may reflect different populations.

Limitations

I did not use the full RMET or the full SIP–ABQ to keep the survey short. This will likely have lowered the power of these instruments to detect an effect. While samples for some groups were sufficient but small (Red Pill, Black Pill, and Incels) others were too small to really be useful (for example, FDS had 7 people). I used Cohen’s d to estimate effect sizes; effects were basically the same with Hedges g correction estimates, so I reported only Cohen’s d. As the incel group was not a large sample and because these are comparisons of ordinal data, the estimated effect is most likely larger than the real effect.

As reported in the results, some participants who reported as identifying with the incel subculture also reported having had sex within the last three years. These may be mischievous participants or may be considered erroneous responses, but it is also possible that some people identify with the incel subculture despite being able to form sexual relationships. This didn’t change the main finding, but it is important to take into account when looking at this population.

This used an online survey so it will be susceptible to opt-in response bias. People who feel they might perform poorly on the tests might not take it. In social media feedback, some participants expressed frustration and stated that they did not believe the RMET had correct answers. Additionally, members of stigmatized populations may be hesitant to participate. In social media feedback one person expressed that they did not trust giving data via a Google form (note that no personal identifying information at all, such as names or email addresses, were collected). This will limit sample size and will probably also lower participation from people who might do poorly on the test, which in turn will lower power and the ability to detect effects.

Strengths

The RMET — probably pretty hard to fake. You can either recognize the correct emotions or you can’t. Similarly, the SIP-ABQ has no “correct” answer and thus is somewhat resistant to desirability bias in reports. “Incel” was operationalized in different ways to reflect different meanings of the term.

References

Ballesteros, A. S., & Ibanez, A. (2021). Dimensional and transdiagnostic social neuroscience and behavioral neurology. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience: Second Edition (pp. 190-202). Elsevier.

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., & Plumb, I. (2001). The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 42(2), 241-251.

Bomfim, A. J. D. L., Ferreira, B. L. C., Rodrigues, G. R., Pontes Neto, O. M., & Chagas, M. H. N. (2021). Lesion localization and performance on Theory of Mind tests in stroke survivors: a systematic review. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo), 47, 140-145.

Bora, E., Walterfang, M., & Velakoulis, D. (2015). Theory of mind in behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 86(7), 714-719.

Cavico, F. J., Muffler, S. C., & Mujtaba, B. G. (2012). Appearance discrimination, lookism and lookphobia in the workplace. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 28(5), 791-802.

Coccaro, E. F., Noblett, K. L., & McCloskey, M. S. (2009). Attributional and emotional responses to socially ambiguous cues: Validation of a new assessment of social/emotional information processing in healthy adults and impulsive aggressive patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(10), 915-925.

Costello, W., Rolon, V., Thomas, A. G., & Schmitt, D. (2022). Levels of well-being among men who are incel (Involuntarily Celibate). Evolutionary Psychological Science, 8(4), 375-390.

Dodell-Feder, D., Felix, S., Yung, M. G., & Hooker, C. I. (2016). Theory-of-mind-related neural activity for one’s romantic partner predicts partner well-being. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(4), 593-603.

Esménio, S., Soares, J. M., Oliveira-Silva, P., Gonçalves, Ó. F., Decety, J., & Coutinho, J. (2019). Brain circuits involved in understanding our own and other’s internal states in the context of romantic relationships. Social neuroscience, 14(6), 729-738.

Greenberg, D. M., Warrier, V., Abu-Akel, A., Allison, C., Gajos, K. Z., Reinecke, K., … & Baron-Cohen, S. (2023). Sex and age differences in “theory of mind” across 57 countries using the English version of the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(1), e2022385119.

Mitchell, R. L., & Phillips, L. H. (2015). The overlapping relationship between emotion perception and theory of mind. Neuropsychologia, 70, 1-10.

Moskalenko, S., González, J. F. G., Kates, N., & Morton, J. (2022). Incel ideology, radicalization and mental health: A survey study. The Journal of Intelligence, Conflict, and Warfare, 4(3), 1-29.

Moskalenko, S., Kates, N., González, J. F. G., & Bloom, M. (2022). Predictors of Radical Intentions among Incels: A Survey of 54 Self-identified Incels. Journal of Online Trust and Safety, 1(3).

Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. Journal of personality and social psychology, 35(4), 250.

Scaptura, M. N., & Boyle, K. M. (2020). Masculinity threat,“Incel” traits, and violent fantasies among heterosexual men in the United States. Feminist Criminology, 15(3), 278-298.

Sparks, B., Zidenberg, A. M., & Olver, M. E. (2023). One is the loneliest number: Involuntary celibacy (incel), mental health, and loneliness. Current Psychology, 1-15.

Speckhard, A., & Ellenberg, M. (2022). Self-reported psychiatric disorder and perceived psychological symptom rates among involuntary celibates (incels) and their perceptions of mental health treatment. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 1-18.

Yirmiya, N., Erel, O., Shaked, M., & Solomonica-Levi, D. (1998). Meta-analyses comparing theory of mind abilities of individuals with autism, individuals with mental retardation, and normally developing individuals. Psychological bulletin, 124(3), 283.

1 comment

40% of people who identified with the incel subculture reported having had sex either within the past 12 months or 3 years.

I had sex only with prostitutes. I think I continue to be incel.