Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

Since beginning DatePsychology just two years ago, we have run approximately 20,000 participants across more than 30 surveys (the results of 27 surveys are published as articles currently; some of the data we are still working through for future articles). Six studies have been partial or conceptual replications. We have also validated and created two scales: a scale measuring mate value (the “Chad Scale”) and a scale measuring “woke” attitudes (the “Woke Scale”).

For our surveys, we collect samples from social media platforms (primarily YouTube and Twitter/X) and from this website. Occasionally, people who are a little less familiar with research methodology get confused about this. Can you use social media to collect samples? Maybe it doesn’t sound very science-y to them. They might imagine men in white coats sitting in a lab and engaging in some esoteric procedure to recruit study participants.

In addition to all of the surveys we have run, I have also spent the last year as the proverbial man in the white coat (I never actually wore such a coat). I conducted research in a neuroscience laboratory and recruited participants to take part in physical experiments. I am sure this looks more science-y: we place electrodes on the bodies of participants while they take part in experimental tasks. All of the psychophysiological measurements of research subjects are displayed on screens and subsequently analyzed. We use a lot of machines, cables, wires, and even administer electrical shocks for classical conditioning procedures. It is everything you would imagine in a stereotypical neuroscience laboratory setting.

All of that said — our sample methodology in the neuroscience laboratory was exactly the same as it is across the sciences. We used undergraduate students. Research participants found our study through an online platform and signed up to participate in exchange for course credit. Almost every university in the world has an online platform like this (many are shared across universities) and this is how most samples are collected. You simply post your study and students sign up for it. It might be an online survey or it might require them to come into the lab, but in both cases the sample is the same. If you have an undergraduate degree in the social sciences there is a high chance that you have participated in a study like this (these studies are often mandatory for students; you need credits from participation in studies for your coursework).

Samples like this have certain characteristics. They are classically WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) (Henrich et al., 2010). They are also highly homogenous: imagine a classroom full of undergraduate psychology students with a mean age of 19 and a standard deviation of 2 years. They are not representative of the “general” population at large (e.g. the entire population of the United States).

Does that make them useless? The fact that they are the most common form of sample across the sciences should clue you in to the fact that most researchers do not think so (or they would not use them). Regardless of what you may have learned on-paper in an intro to stats course about representative sampling, you can make at least some inferences about human psychology from non-representative samples. This is because human beings share psychological, behavioral, and physical traits across populations.

You often will not have access to the full population that you have interest in, making representative samples (which require a random sampling of the full population) impossible to acquire. For example, if you want to study Alzheimer’s patients you will never have access to every single person who has Alzheimer’s disease. Instead, you will simply collect a sample of Alzheimer’s patients from a local hospital. If you want to study incels (involuntarily celibate men) you will never have access to every incel in the world (or country, or city) for a random sample. However, because brains — and human psychological mechanisms more broadly — work similarly you can draw some conclusions outside of your sample.

Admittedly, convenience samples like this are bad for one thing: representative descriptive statistics. To illustrate, in my surveys >70% of participants have a bachelor’s degree or above. I would not conclude that 70% of Americans have a bachelor’s degree from this (from the U.S. Census Bureau’s representative data, only about 38% of Americans have a bachelor’s degree). That’s pretty intuitive; I think it makes sense to most people. Knowing your sample lets you determine what you probably shouldn’t conclude from it.

On the other hand, across my surveys when I run measures of sociosexuality I consistently see sex differences with a Cohen’s d of .7 to .9. Men have higher sociosexuality than women do. That men have higher sociosexuality (and that the effect size is large) is highly replicated across research in evolutionary psychology, both in representative and non-representative samples. This is simply a sex difference that we see between men and women broadly, so it emerges regardless of your sample. Similarly, if you sample alcoholics with Korsakoff’s syndrome you will see similar lesions on fMRI. It does not matter if they are from New York City or Moscow. The brains and psychology of different populations don’t work that differently, in many cases.

The student convenience sample is the most common sample, but following student samples online surveys are the second most common sample in the social sciences. Convenience samples in general make up over 95% of samples (Jager et al., 2017). Multiple platforms exist to collect samples of paid participants (e.g. MTurk or Prolific) and researchers increasingly use social media (e.g. Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter/X) to collect samples. These have the same basic limitation that student convenience samples do: they are non-representative. Beyond that, there is no difference in the rigor or quality of a sample sourced from social media and a student sample. Online convenience samples are probably less homogeneous in some ways, which may be a strength relative to student samples. Nonetheless, convenience samples often produce results similar to representative samples regardless of the platform used (Coppock et al., 2018; Gosling et al., 2004; Mullinix et al., 2015).

Replication Is The Key

Since most samples are non-representative and come from different populations, how do we know the results of a given sample are not anomalous to that sample (or only reflective of traits unique to the population the sample is drawn from)? The answer, as far as I can tell, is replication. Replication is independently repeating experiments or studies to validate past findings and ensure the reliability of results. Diversity across samples is important here, too. For example, to know that your results are not merely reflective of undergraduate college students you might want a more diverse sample (for example, one recruited from social media).

I don’t have much more to write about that, except that online samples are far from being worthless. They facilitate replication efforts and add to the body of knowledge on a given topic as well as any other sample. Individual studies don’t prove theories directly, but do test hypotheses that support theories. Lines of research — or the total body of research conducted on a topic across studies — support theories. Evidence may be amassed across diverse samples, with or without representativeness.

Convenience Samples Are Tools of Experienced Researchers, Too

Some of what I have written on DatePsychology could be summed up as “how the manosphere gets evolutionary psychology wrong.” This has resulted in social media debates with manosphere influencers and their fans (none of whom are psychologists, none of whom have produced any research, and none of whom have any real-world experience with sampling). It is always denizens of these subcultures, rather than psychologists, who have a bone to pick with study results that don’t validate their ideology. This doesn’t stop them from occasionally citing papers that use the exact same methodology (because they probably don’t read the papers they post).

It’s a clear cope: they don’t like the results of a given study and want an excuse to dismiss or deny those results.

I have read comments to the tune of “no experienced researcher would ever use that sample” or “you would fail an undergraduate course for that sample.” We are talking about people who have no formal training in psychology nor research themselves, so I can’t imagine how they would even know. It isn’t as if they have ever been in the position to fail a student or review research papers themselves. They are also objectively wrong. If anything, it is more characteristic of the undergraduate freshman to believe that samples must be special. Experienced researchers use samples from social media often. No one is failing classes for using samples from social media — and good papers, written by good scientists, get published in good journals with samples from social media.

Beyond manosphere debates and discourse, many of the people who read DatePsychology and interact with me on social media are aspiring psychology students. They are genuinely curious about how research is conducted. Many want to go on to become psychologists.

For them, I hope that this is a helpful article that explains how research is commonly conducted in psychology. I also hope that this helps them understand that doing science isn’t something outside of their grasp. The methods used to collect samples, test hypotheses, and to follow the scientific method in general are not that complex nor are they restricted to esoteric practices that can only be performed by white coats in an ivory tower. If you want an idea of what you might be doing as a researcher in personality or evolutionary psychology, at least as far as sample collection is concerned, this article will show you a small slice of that.

The takeaway from this section is this: collecting samples online is a standard and common methodology used by experienced researchers. Studies in psychology (and in the sciences more broadly) use this methodology frequently, researchers in evolutionary psychology use this methodology frequently, and studies with convenience samples (using students, social media, or anything else) are regularly published in high-quality journals. In the next section we will illustrate this.

Reviewing Samples in Evolutionary and Personality Psychology: Dark Triad Research

We examined the sampling methodology described in every paper cited in a recent article (Is the Dark Triad Really Attractive? A Review of the Literature). Excluding papers without original samples (e.g. meta-analyses), the sampling methodology of 90 papers was assessed. For papers with multiple samples or studies, only the first sample was coded for simplicity.

Of the 90 papers, only one paper had a representative sample. This paper used the German Socio-Economic Panel Innovation Sample (SOEP-IS) (Weber et al., 2021). A second paper reported having a representative sample, but upon examination used a nonrepresentative Qualtrics sample (described in a subsequent section below).

The most common sampling method was a student convenience sample (49 of 90 samples). As described above, this involves recruiting students available on campus (usually undergraduates through an online platform in exchange for mandatory university credit).

36 of 90 of the samples analyzed used online survey sampling methods. Of these, 18 of the 39 specified recruitment of participants through social media websites by name (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram). In 9 samples, use of an “online survey” was reported without specifying where online survey participants were recruited. In 8 online samples, the paid online sampling platform Amazon MTurk was used. 5 samples listed other survey platforms (Qualtrics, SurveyMonkey, SoSci Platform, and Respondi).

For the remaining papers, 4 described snowball sampling via friends or peer groups, 2 recruited through newspaper or media advertisements, 2 recruited samples through high schools, 2 recruited samples through facilities (a correctional facility and a counseling center for women), 2 reported adult volunteers drawn from the university campus, and 1 paper did not report the source of the sample.

The next section contains excerpts from papers describing common sampling methods.

Examples of Typical Sampling Methodology

Student conveniences samples:

“We relied on 223 women (Mage = 20.27, SD = 4.28), undergraduate students in psychology, with an age range between 18 and 47 years, recruited from a Personality assessment course. We advertised the study during a lecture and those that wanted to participate contacted the first author via e-mail. All the participants were informed of the nature of the study. We administered the measures online using Google Forms. We offered all the participants one extra credit point for the Personality assessment course.” (Burtaverde, 2021)

“We recruited a group of 210 healthy college students (107 men and 103 women) at the University of Turku in Finland. The mean age was 22.93 years (SD = 4.55) for men and 21.16 years (SD = 3.08) for women. Participants received detailed information about the aim of the study following the approval of the appropriate local ethics committee, signed an online letter of informed consent, and answered a general data questionnaire that included: age, current marital status, and number of previous sexual partners. The participants did not receive any compensation for taking part in the research.” (Borráz-León & Rantala, 2021)

Online sampling through social media and MTurk:

With purposive sampling, 140 respondents, whose age ranged from 18 to 40 (M = 22.57, SD = 3.45) from a predefined population were collected … The responses were collected through social media platforms including Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn by online questionnaire.” (Alavi et al., 2018)

“We have recruited 160 US American participants via Amazon Mechanical Turk. Participants were paid $0.30 for their participation.” (Alper et al., 2021)

Snowball sampling via peer or friend groups:

“The data collection took place in two phases. The first group of participants were undergraduate psychology students at the university. They completed the questionnaire as part of a course focused on participation in research projects. In the second phase of the study, additional participants were recruited by the students, and data collection continued via the snowball sampling method. Participants in the second phase were recruited through personal connections and contacted by email, where they were provided with basic information about the research. After they had consented to participate, a link to an online questionnaire was sent to them by the students. Data collection took place using the Survio platform. This data collection method combines the advantages of an anonymous questionnaire (online format with data collection on an external platform) and controlled data collection (the students approached participants they knew.” (Demuthova et al., 2023)

Qualtrics “Representative” Samples

One study reported collecting a “representative” sample through Qualtrics:

“A nationally representative sample of 1000 men aged 18–40 obtained through Qualtrics completed an online survey in March 2014. These data were part of a larger data gathering initiative instigated by a national magazine.” (Fox & Rooney, 2015)

However, Qualtrics provides quota samples rather than representative samples. From Qualtrics: “The majority of our samples come from traditional, actively managed, double-opt-in market research panels. While this is our preferred method, social media is occasionally also used to gather respondents. Upon client request, we can also access other types of sources to meet the needs of a specific target group” (Qualtrics, 2018). In an article on sampling for graduate students, Harrington (2019) wrote, “Technically the Qualtrics Online Sample is not a true random sample, but rather a quota sample .. qualtrics uses a quota sampling method, where they attempt to make the sample they give you share the same demographic characteristics as the population you are trying to study.”

I just wanted to make a brief note on this, because occasionally samples are reported as “representative” when they are not strictly speaking.

Journals and Impact Factor

The above is one illustration of how convenience samples are the norm in evolutionary and personality psychology. Further, many of these samples are drawn from online surveys (and many of those are from social media platforms).

Does that make them low quality samples that aren’t taken seriously by “real” researchers? One way we can look at that is by analyzing the journals that they are published in.

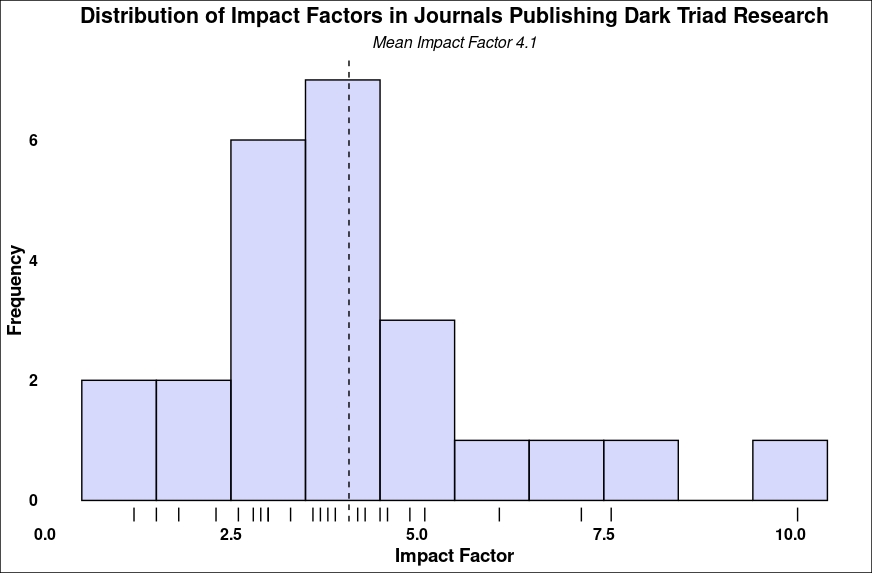

Below are the impact factors of the journals the aforementioned 90 papers were published in. Each journal is only counted once, although some good journals were overrepresented. For example, 27 papers were published in Personality and Individual Differences, one of the top journals in personality psychology.

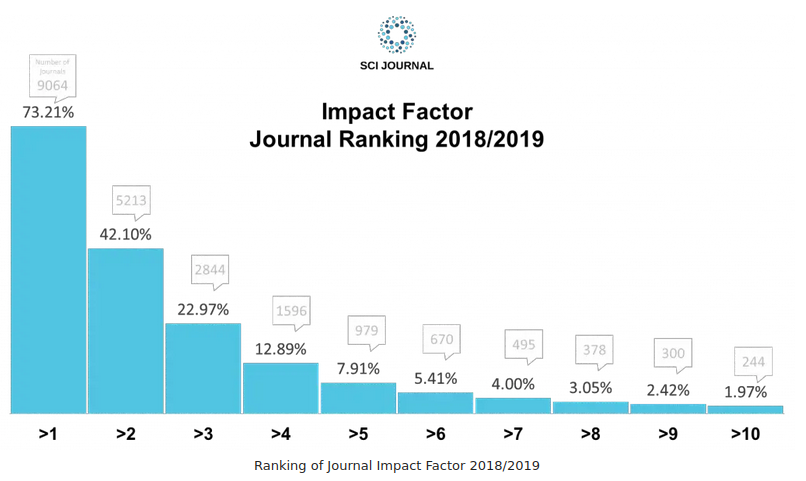

It’s tricky to know what a good impact factor is; impact factors should be compared across journals that publish similar topics. A good journal that has more of a niche will have a lower impact factor. That said, Sci Journal has plotted what the impact factors of journals are:

The histogram above is for all journals. For psychology specifically, journals with an impact factor of 2.96 are in the top 20% of journals.

What about papers that used samples from social media specifically, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter — are these published in worse or less reputable journals (as you might expect if they were “low quality,” or bad methodology)?

Nope.

63% of these were published in Personality and Individual Differences, which has an impact factor of 4.3. The rest were published in the European Journal of Psychology (IF 3), Scientific Reports (IF 4.6), and Comprehensive Psychiatry (7.2). The mean IF is 4.8; journals using samples from social media were published in journals with a slightly higher impact factor on average.

The takeaway from this section is that good journals in psychology don’t reject papers that use samples from social media. Simple as. The editors and peer reviewers of good journals don’t tend to reject papers merely for using convenience samples (even from social media).

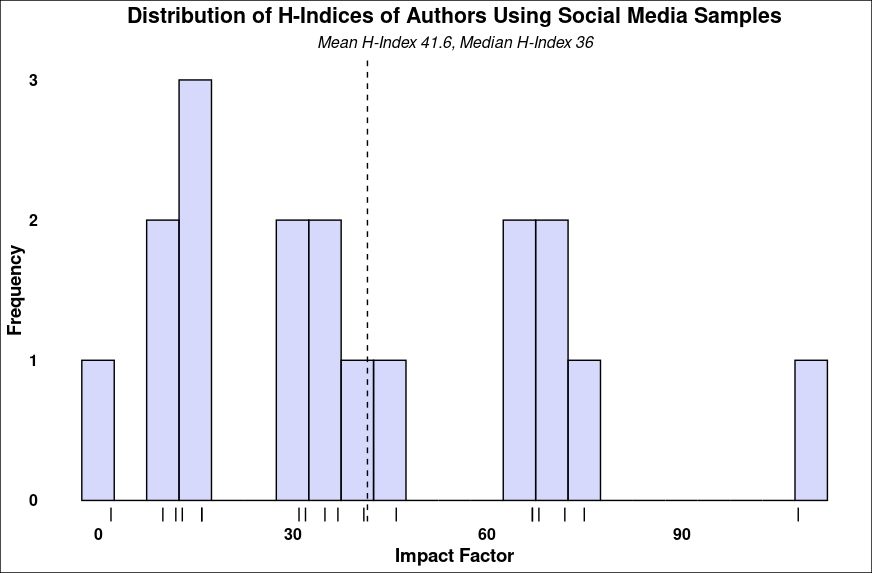

H-Index of Authors

Are convenience samples (of students or collected online) the tool of less experienced or less qualified researchers? We can look at the authors of the 90 publications to determine that.

An h-index is a score derived from the publication history and the impact (based on how many other scientists cite a paper) of a researcher. It is the currency of academia. The h-index tells you who is getting referenced a lot. The more experienced the researcher, the more they publish, and the more their papers get cited the higher their h-index will be.

According to Hirsch (2005) (he came up with the h-index):

- An h-index of 20 is characteristic of a successful scientist after 20 years of research.

- An h-index of 40 is characteristic of outstanding scientists after 20 years.

- An h-index of 60 is uncommon and characteristic of the elite researcher after 20 years.

This was in 2005 and in the field of physics, but it gives you a starting frame of reference. Nosek et al. (2010) examined the h-indices of social psychologists specifically and found an average h-index of 21.3 with a standard deviation of 14.8. This gives you another point of reference.

A few websites list h-indices typical of different stages within one’s academic career. We can look at one from Academia Insider for the social sciences:

- An h-index of 1-3 is the range of a PhD student.

- An h-index of 4-12 is the range of a postdoctoral student.

- 19-22 is the range of an assistant professor.

- 17-35 is the range of an associate professor.

- 29-55+ is the range of a full (or tenured) professor.

Now you have the gist of what the h-index of a new or established research psychologist might look like.

Below are histograms of the lifetime h-indices displayed by Google Scholar profiles for the authors of the 90 papers reviewed and for authors using samples from social media. All first authors were included. Second and subsequent authors were included if they had a Google Scholar profile.

The mean h-index for all authors was 33.1 and the median was 24. For papers using social media samples, the mean h-index was 41.6 and the median was 36.

The takeaway from this section is that more experienced researchers in evolutionary and personality psychology also use samples drawn from social media.

Discussion

Hopefully this article demystifies the sampling process. At the end of the day, researchers overwhelmingly use the sample that they have at hand. In most cases it is really that simple. This is why statisticians have the expression “the best sample is the one that you have.”

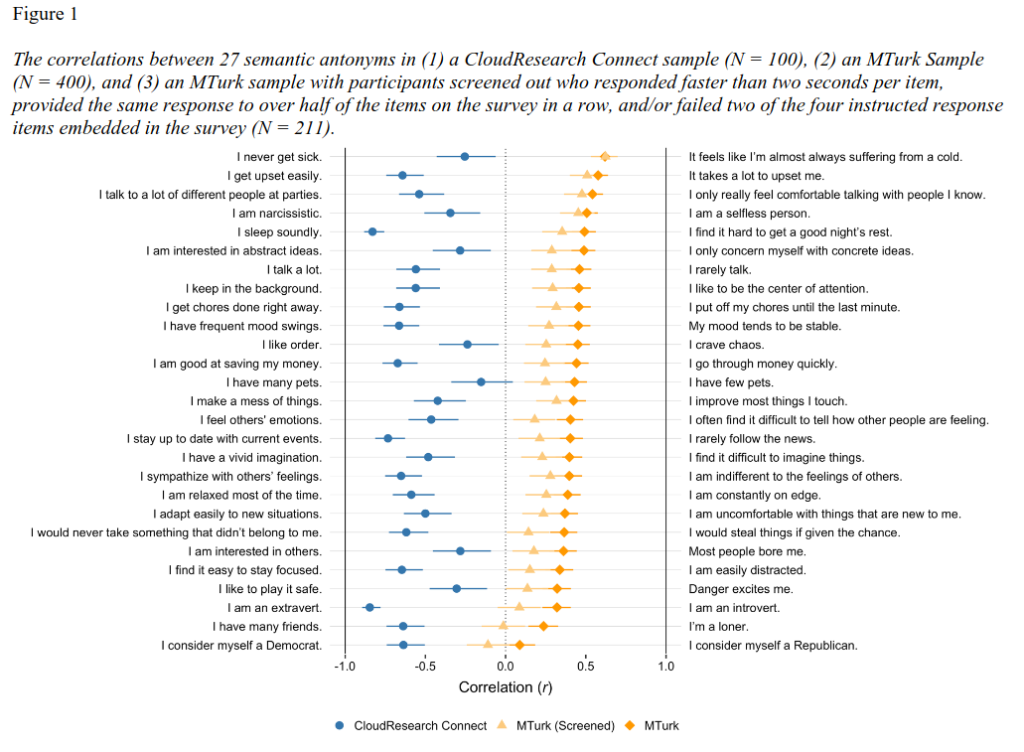

A final word should be made in respect to the online sampling platform Amazon MTurk. A recent paper by Kay (2024) entitled “Extraverted introverts, cautious risk-takers, and selfless narcissists: A demonstration of why you can’t trust data collected on MTurk” found some serious problems with this platform.

As described in the introduction, MTurk is one of a number of paid online platforms for collecting samples. Survey-takers sign up and get paid a fee for every survey that they complete. This probably worked really well in the beginning. Now, unfortunately, it seems to be populated by people (and bots) that speed through surveys as fast as they can.

Kay (2024) found that results using this platform were mostly junk; participants responded affirmatively to 77.78% of semantic antonyms (e.g. “I never get sick” and “I’m almost always suffering from a cold.”). Approximately half of the participants failed checks for careless responding (e.g. straightlining, or simply marking the same answer on every item).

You can see the effects for each item above. Items that should not be correlated were uncorrelated in the CloudResearch sample, but almost all had positive correlations in the MTurk sample.

These are all things we check for in every survey at DatePsychology. It’s extremely rare that we find failed attention checks or straightlining (usually just 1 or 2 participants, often 0, for a given survey). In other words, getting a sample from social media (where people have an intrinsic motivation to participate) is probably a lot better than MTurk, despite MTurk being the most common paid online platform for recruiting participants.

References

Coppock, A., Leeper, T. J., & Mullinix, K. J. (2018). Generalizability of heterogeneous treatment effect estimates across samples. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(49), 12441-12446.

Gosling, S. D., Vazire, S., Srivastava, S., & John, O. P. (2004). Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about internet questionnaires. American psychologist, 59(2), 93.

Harrington, 2019. Thesis Advice: Information on getting a representative sample from Qualtrics (Australia). https://methods101.com.au/docs/thesis_advice_2_qualtrics_samples/

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world?. Behavioral and brain sciences, 33(2-3), 61-83.

Hirsch, J. E. (2005). An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proceedings of the National academy of Sciences, 102(46), 16569-16572.

Jager, J., Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2017). II. More than just convenient: The scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 82(2), 13-30

Kay, C. S. (2024, April 28). Extraverted introverts, cautious risk-takers, and selfless narcissists: A demonstration of why you can’t trust data collected on MTurk. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/zs6pk

Mullinix, K. J., Leeper, T. J., Druckman, J. N., & Freese, J. (2015). The generalizability of survey experiments. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 2(2), 109-138.

Qualtrics, 2018. 28 Questions to Help Buyers of Online Samples. https://www.iup.edu/arl/files/qualtrics/esomar.pdf