Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

“People Lie:” Epistemology, Your Feelings, and Quantifying Evidence

There are inherent limitations to studying human behavior and human psychology. We can’t see into the mind, we can’t see into the past, nor can we directly observe behavior in many (even most) cases. Many questions can only be answered by asking people. Therein lies the problem, because we know people can lie. We also know that people are motivated to lie under certain circumstances.

However, knowing that people can lie tells you relatively little. For example, we know that people are much more inclined to lie about sensitive issues if a survey is administered face-to-face rather than anonymously (Nnko et al., 2004). The magnitude of the effect is also important. Inaccurate reports that deviate only slightly from the true figure may not be meaningful at all — and only a small portion of survey respondents may be inaccurate reporters. This will leave your data, albeit imperfect, a very close estimate to the true figure within the population.

In other words, merely asserting “people lie” is not sufficient to tell you anything. You must determine if people are lying in a given instance and if those lies are large enough to mean anything.

In popular dating discourse “people lie” has also become a cope used to dismiss perfectly good data when it challenges people’s feelings and intuitions about base rates (the frequency of an occurrence within a population).

Let’s say you hear that approximately 5% of men are virgins at age 25 (this is the estimate given to us by the large representative National Survey of Family Growth, or NSFG). Does this seem accurate to you or does it seem too low? Do you believe more men at age 25 are still virgins?

Regardless of what you believe you should ask yourself why you believe what you do. If you believe that it’s 5% you’re probably just basing it on what the data says. Perhaps it’s also easier to believe an estimate of 5% if most 25-year-old men who you know are not virgins.

Conversely, it might be harder to believe a 5% estimate if you know a lot of 25-year-old virgins. It might not jibe with your “personal experience,” or if you prefer, “lived experience.”

Yet, “lived experience” is a terrible way to estimate base rates. We know from research in judgment and decision-making that people are notoriously bad at guessing prevalences in the population (Bar-Hillel, 1990; Koehler, 1996; Rettew, 1993). It can actually still be useful — this is a form of heuristic decision-making. It’s important to understand that heuristic decision-making is also emotional decision making. You are guessing at a number based on the way that you feel.

A great deal of research has shown how salience shapes inaccurate estimates of base rates (Kahneman, 2002). What this means is that the more you are exposed to something then the more frequent you will believe its occurrence is — even if it’s actually very rare. A good example of this can be found in police shootings or police brutality. Americans report that police brutality is much more common than it really is: a product of non-stop exposure to media coverage, protests, and social media discourse on police shootings (see: Perceptions Are Not Reality: What Americans Get Wrong About Police Violence).

This occurs in popular dating discourse, too. If you repeatedly hear fringe beliefs then you may come to think those beliefs are more widely held than they really are. If you participate in communities of men who struggle to date you may come to believe that many men share the same struggles. This is the risk of living in a bubble: what “feels” right to you will be off. What you think is “common sense” may not be a common belief at all. (In fact, what is “common sense” to you may seem unhinged and untethered from reality by most people.) Your “personal experience” will be, at best, a small and nonrepresentative sample drawn from the failing tail of the mating distribution.

Scientists are not permitted to defer to their own emotions and “lived experience” as the final epistemological word. They must show things to be true. Anyone who appeals to an internal state of belief (“common sense,” “personal experience,” “it’s obvious,” or “everyone knows it, bro”) can only assert things to be true. The former is empirical evidence and the latter might as well be made up.

Let’s say you “know” (by which you actually mean you feel and have an intuition or hunch) that “people lie” on surveys. At best what you really have is a hypothesis. Now it’s up to you to provide evidence in favor of it. You don’t really know anything yet. You are tasked with quantifying “people lie;” showing that it is true and showing the extent to which people lie. You must do so following the scientific method and showing empirical evidence, which brings us to our next section:

The Bogus Pipeline: A Fake Lie-Detector Methodology for Uncovering Social Desirability Bias

The bogus pipeline is a research methodology used in psychology to uncover socially desirable or dishonest reporting. The procedure consists of hooking survey participants up to a fake polygraph, or “lie detector.” It doesn’t matter if polygraphs can really detect lies or not (and the general consensus is that they cannot), because people think that they can, and merely having the electrodes placed can induce participants to change their responses. In effect, participants think they will be caught if they lie and therefore are less inclined to report inaccurately.

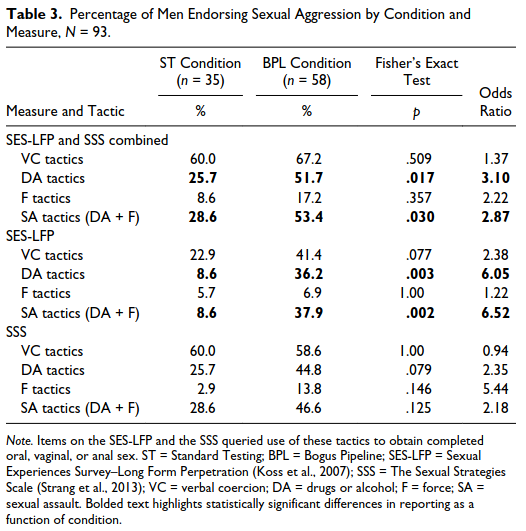

This methodology works. Strang and Peterson (2020) utilized the bogus pipeline to assess men’s self-reports of sexually aggressive behavior. Under the fake lie detector, in comparison with simple survey administration in the lab, men were 6.5 times more likely to admit to illegal sexual assault. This is a huge difference. The table below from Strang and Peterson shows these results:

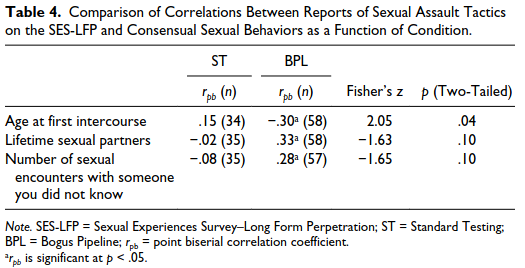

Strang and Peterson (2020) also examined self-reports of men’s lifetime number of sexual partners. The table below shows from Strang and Peterson shows these results. Although the bogus pipeline shifted self-reports of sexual assault tactics by a large degree, it did not shift self-reports of sexual partner count significantly:

This study is a great place to begin for checking the usefulness of the bogus pipeline methodology. Herein we have items that represent the peak of social desirability bias: getting men to admit to serious sexual crimes. To put it another way, we know that the bogus pipeline can elicit more honest self-reporting for even the most sensitive self-report items and we know that the effect of the change in self-reports is very large. Subsequent research has also confirmed the effectiveness of the bogus pipeline in eliciting more honest reporting for sexual assault (Ross et al., 2024).

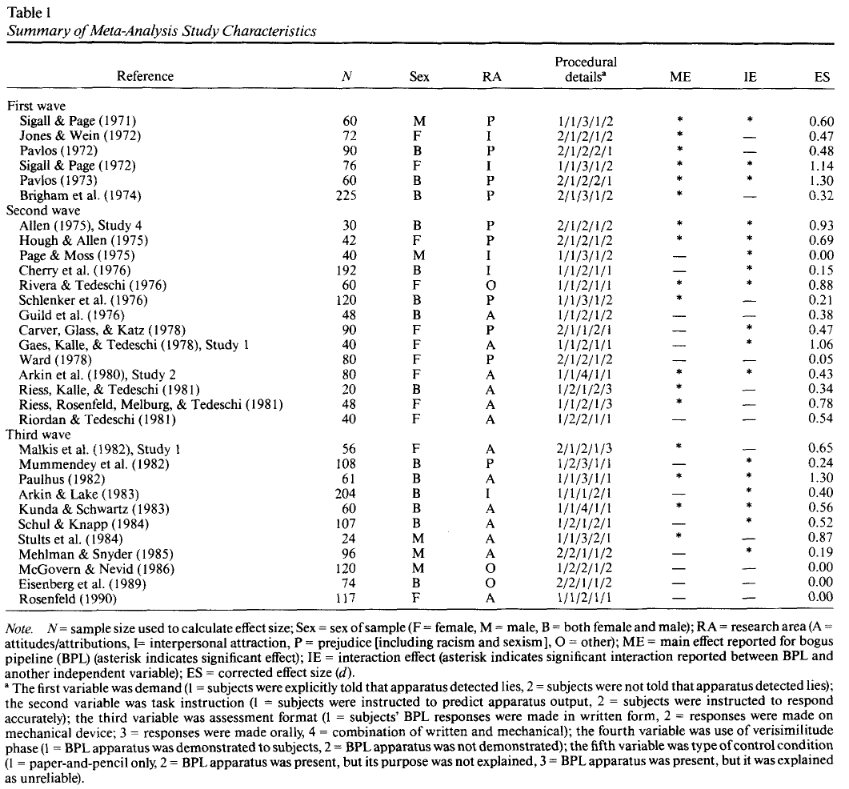

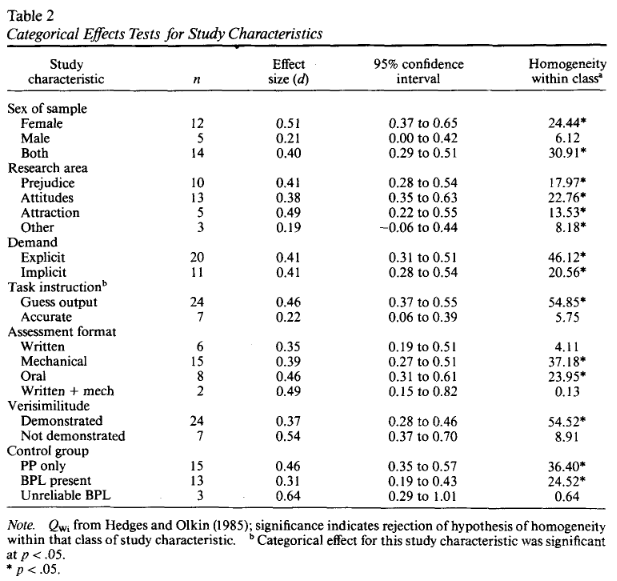

An earlier meta-analysis examined the effectiveness of the bogus pipeline as well (Roese & Jamieson, 1993). This consisted of 31 studies across different domains or research topics. Tables 3 and 4 show the results for each study and the nature of the experimental tasks. The bogus pipeline was broadly effective at eliciting medium-sized effects across different tasks.

Does the Bogus Pipeline Shift Self-Reports of Sexual Partner Count?

We have seen that the bogus pipeline works and that it can elicit more honest reporting across a diverse range of tasks. However, what we are really interested in are self-reports of sexual partner count. Early research on sexual behavior found a “swagger and secret” effect: men exaggerate their number of sexual partners while women reduce their past number of sexual partners (Nnko, 2004). This is observed when comparing self-reports received by in-person interviews with self-reports received on anonymous surveys.

With in-person interviews, men report more sexual partners and women report fewer sexual partners than on anonymous surveys. These findings also led to a simple and effective methodological recommendation for studying sexual behavior: use anonymous surveys. If you ask people face-to-face they may be shy (or boastful), but on anonymous surveys there is little to gain or lose.

This may seem obvious, but keep in mind that until fairly recently we did not have the Internet and were not able to administer anonymous surveys. Participants were often required to visit the experimenter in person and fill out a paper-and-pencil form.

Two major studies were done examining self-reports of sexual partner count in 2003 and 2013. Both of these are frequently referenced and were widely reported in popular science media. Here is how Google Search displays accounts of those results:

Alexander and Fisher, 2003

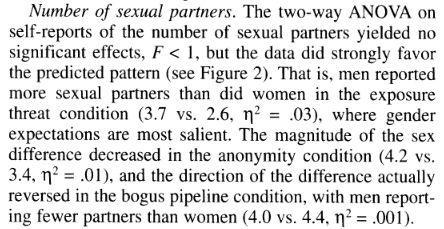

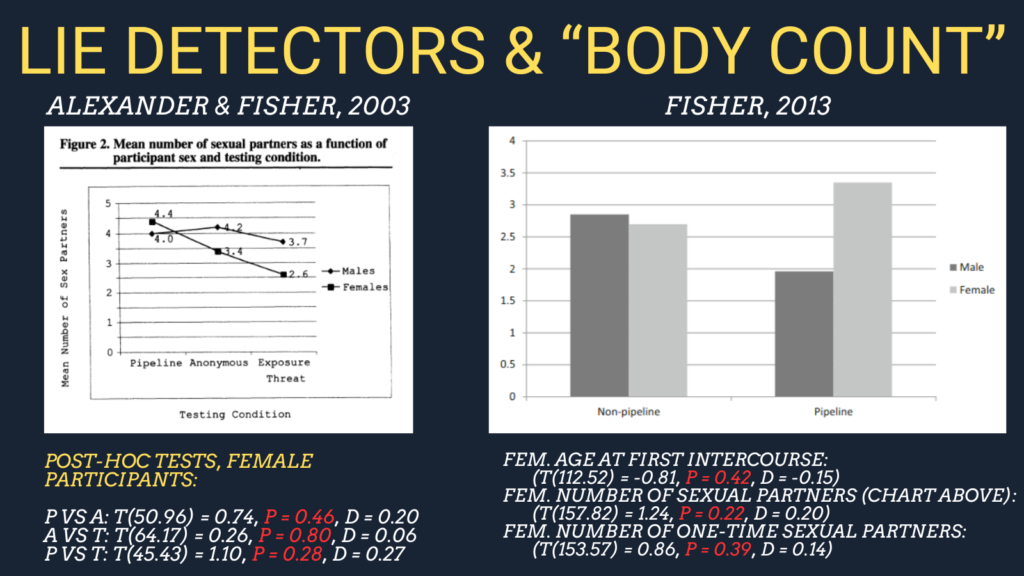

Alexander and Fisher (2003) examined self-reports of sexual partner count under three conditions: an “exposure threat,” or in-person, an anonymous survey, and the bogus pipeline. Below is an excerpt from the results:

Alexander and Fisher (2003) did not find a significant difference and the reported effect size is very small. Although it has been widely misreported in coverage of this paper that the fake lie detector revealed a difference, as far as sexual partner count it did not. It turns out that anonymous reporting is fine for eliciting truthful responses about past sexual partner count.

Here is the oft shared image from this paper:

Although post-hoc comparisons of groups were not reported in this paper, we can calculate those from the data provided:

Pipeline vs Anonymity: t(50.96) = 0.74, p = 0.46, d = 0.20

Anonymity vs Threat: t(64.17) = 0.26, p = 0.80, d = 0.06

Pipeline vs Threat: t(45.43) = 1.10, p = 0.28, d = 0.27

Basically nothing is there. There was no significant difference between groups. Although I am not a fan of Nassim Taleb, his phrase fooled by randomness certainly applies here. A lot of people seem to have seen a line going up and believed that the effect was real. Given the null hypothesis, the pattern of observed data could occur by random chance alone.

Fisher, 2013

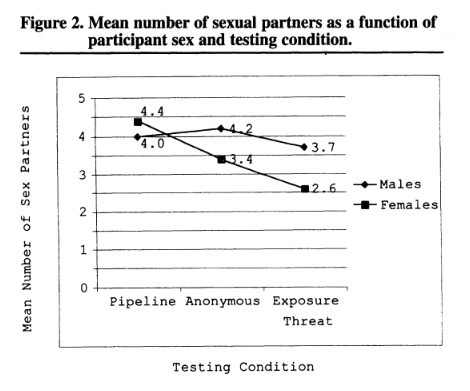

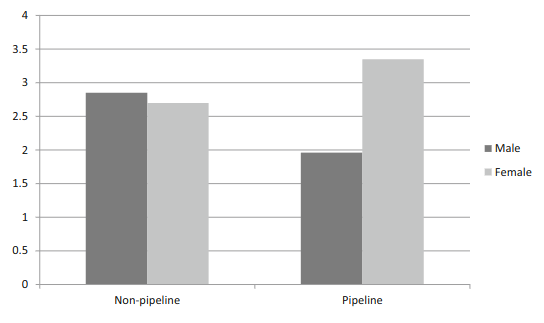

Fisher (2013) examined this again one decade later. Below are the results:

Although at a glance it may seem like something happened here, this shows no main effect for the condition (non-pipeline vs pipeline) (F(1, 284) = .71, p=.40, ηp2 =.00). An interaction effect was observed however, with women reporting more partners than men in the pipeline condition. This was very small (F(1, 284) = 6.94, p=.009, ηp2 =.01). Importantly, the methodology of Fisher (2013) combined the anonymous and exposure threat conditions used in Alexander and Fisher (2003). Participants were still required to attend the lab in person and be hooked up to a machine in the non-pipeline condition; despite that significant and meaningful differences did not emerge.

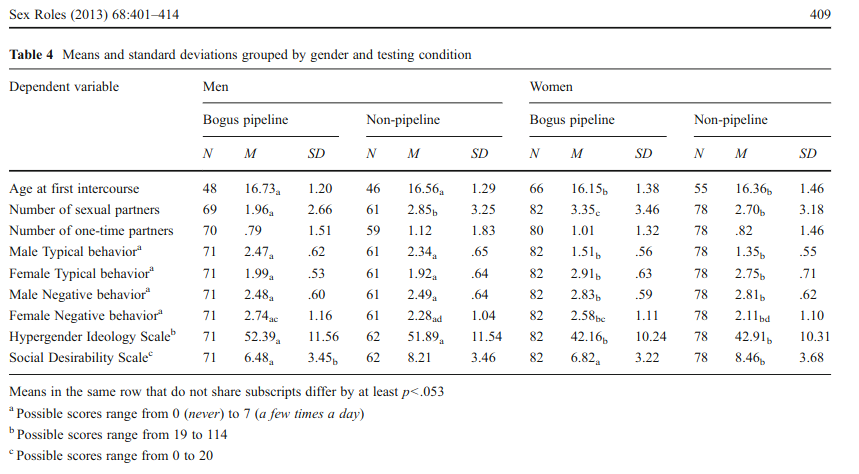

We can look at the relevant questions and data from the paper to calculate test statistics as we did for Alexander and Fisher (2003). Below is a table of results from Fisher (2013):

For women, age of first sexual intercourse was not significantly different between the bogus pipeline and non-pipeline condition (t(112.52) = -0.81, p = 0.42, d = -0.15).

For women, number of sexual partners was not significantly different between the bogus pipeline and non-pipeline condition (t(157.82) = 1.24, p = 0.22, d = 0.20).

Finally, for women, number of one-time sexual partners was also not significantly different between the bogus pipeline and non-pipeline condition (t(153.57) = 0.86, p = 0.39, d = 0.14).

I didn’t go through and do the rest of them as they are less pertinent to the question of misreporting sexual behavior, but as we see the introduction of the fake polygraph didn’t actually budge women’s reports of sexual behavior across two separate studies.

Finally here is a graphic of the results above for your use as these charts tend to get circulated often:

Discussion

As far as I know, Fisher and Alexander (2003) and Fisher (2013) are the only studies to have done this to date. At the very least these are the two papers that made it into popular science media and that get frequently referenced in online discussions. However, neither showed significant differences across conditions!

Perhaps this is a lesson in believing headlines rather than taking the time to read the results. Non-significant results with very small effect sizes filtered into our dating discourse as if they were real.

What these results really show is a win for anonymous surveys: you probably get the same results with anonymous surveys as you do if you hook someone up to a polygraph. Further, given that none of the surveys used were truly anonymous (requiring lab participants to appear in person), you might expect truly anonymous surveys administered online to work even better.

Why doesn’t the bogus pipeline work for female sexual partner count the same way it does for male sexual assault? It may be the case that sexual partner count just isn’t as taboo as a lot of people seem to believe it is. Further, participants may actually believe that they have nothing to hide nor lose from the honest reporting of past sexual partners to a psychologist on an anonymous survey.

Research has shown that sexual double standards (SDS) — such as the belief that a high sexual partner count is good (or acceptable) for men and bad for women — have been disappearing for at least a decade and that most people do not endorse them in respect to past partner count (Allison & Risman, 2013). Recent research has found that men and women both care about past sexual partner count similarly (Stewart-Williams, 2017). In my own research I found that men and women are both highly tolerant of “body counts” in potential romantic partners: the number that is a “deal-breaker” for men and women is multiple standard deviations above the median number of past sexual partners (see: “Body Count” And Sexual Double Standards). Further, individuals with a high “body count” themselves are less likely to care about a high “body count” in potential partners (see: What Is A High Body Count?).

That most men and women are not very promiscuous is shown in every representative dataset that we have (contrary to what I call “promiscuity narratives” circulated by popular media and niche dating discourse). At the same time, a lot of people really don’t care much (and promiscuous people care even less). The people who do care a lot are probably just projecting their own beliefs onto others when they claim that “body count” is such a shameful taboo that self-censoring on anonymous surveys is common. It is feels over reals and has about as much validity as a Dothraki woman telling you “it is known.”

References

Alexander, M. G., & Fisher, T. D. (2003). Truth and consequences: Using the bogus pipeline to examine sex differences in self‐reported sexuality. Journal of sex research, 40(1), 27-35.

Allison, R., & Risman, B. J. (2013). A double standard for “hooking up”: How far have we come toward gender equality?. Social science research, 42(5), 1191-1206.

Bar-Hillel, M. (1980). The base-rate fallacy in probability judgments. Acta Psychologica, 44(3), 211-233.

Fisher, T. D. (2013). Gender roles and pressure to be truthful: The bogus pipeline modifies gender differences in sexual but not non-sexual behavior. Sex Roles, 68(7), 401-414.

Kahneman, D. (2002). Maps of bounded rationality: A perspective on intuitive judgement and choice.

Koehler, J. J. (1996). The base rate fallacy reconsidered: Descriptive, normative, and methodological challenges. Behavioral and brain sciences, 19(1), 1-17.

Nnko, S., Boerma, J. T., Urassa, M., Mwaluko, G., & Zaba, B. (2004). Secretive females or swaggering males?: An assessment of the quality of sexual partnership reporting in rural Tanzania. Social science & medicine, 59(2), 299-310.

Rettew, D. C., Billman, D., & Davis, R. A. (1993). Inaccurate perceptions of the amount others stereotype: Estimates about stereotypes of one’s own group and other groups. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 14(2), 121-142.

Roese, N. J., & Jamieson, D. W. (1993). Twenty years of bogus pipeline research: A critical review and meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin, 114(2), 363.

Ross, J. M., Machette, A. T., & Gonzalez, R. (2024). Testing the reliability of sexual aggression self-reports. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 30(1), 129-143.

Strang, E., & Peterson, Z. D. (2020). Use of a bogus pipeline to detect men’s underreporting of sexually aggressive behavior. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(1-2), 208-232.

Stewart-Williams, S., Butler, C. A., & Thomas, A. G. (2017). Sexual history and present attractiveness: People want a mate with a bit of a past, but not too much. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(9), 1097-1105.