Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

Physical Attractiveness

The role of physical attractiveness, in particular facial and bodily attractiveness, is a robust predictor of success in the early formation of romantic relationships. As early as 1966, Walster et al. found more attractive participants were more likely to be selected in an in-person “computer dance” dating event. More recently, speed dating methodology has opened up avenues for examining revealed preferences in ecologically valid conditions. In initial in-person scenarios, physical attractiveness often emerges as the strongest predictor of mate choice (Asendorpf et al., 2011; Eastwick et al., 2008, 2011; Luo and Zhang, 2009). Back et al. (2011) found a correlation of .47 with physical attractiveness and popularity in a speed dating paradigm. Further, speed date popularity was also associated with physical attractiveness moderated by self-perceived mate value. Individuals who were higher in physical attractiveness perceived their own mate value to be higher, which contributed to speed dating popularity. Poulson et al. (2013) also found that physical attractiveness, as well as anxious and avoidant attachment, predicted a higher number of dateless weeks and a lower likelihood of having a second date.

Locus Of Control

Locus of control (LOC) refers to the extent to which individuals view themselves as agentic over external causes (Rotter, 1966). Those with a high internal LOC feel more in control and more responsible for what events transpire in their own lives. On the other hand, people with a higher orientation toward an external LOC tend to lean more toward “things just happen to me.” Individuals with a higher internal LOC have more depth and commitment in romantic relationships (Prager, 1986). Having a romantic partner or a friend who is perceived to have a higher external LOC also predicts higher dissatisfaction with that friendship (Morry, 2003).

LOC is also related to how people handle conflicts in their own relationships. Canary et al. (1988) found that an internal locus of control was associated with the use of integrative conflict management strategies, while an external locus of control was associated with more avoidance and use of negative communication strategies. An internal LOC within marriage is associated with more open, direct conflict management (Miller et al., 1986). Further, individuals with a high internal LOC engage in fewer avoidance and withdrawal behaviors in relationships (Caughlin & Vangelisti, 2000). Meanwhile, those with a higher external LOC may be more willing to dissolve a relationship and show more neglect within current relationships (Çırakoğlu, 2006). Dion and Dion (1973) found that participants with a higher internal LOC were less likely to view romantic love as a mysterious or idealistic force. As cultural conceptions of romantic love may depict it as something external that just happens to you, those with an external LOC may be less agentic in the pursuit or construction of love within their own romantic relationships. Individuals with a more external LOC may also be less likely to pursue or seek out romantic relationships, instead waiting for one to just happen to them.

LOC also predicts individual differences in attachment styles. Mickelson et al. (1997) found a higher internal locus of control predicted a higher degree of secure attachment. McMahon (2007) found that a higher external locus of control was associated with lower relationship commitment. Further, external locus of control was associated with higher avoidant and anxious attachment. Secure attachment styles also predict a higher degree of self-determination (related to LOC) in romantic relationships (Leak and Cooney, 2001). More extrinsic orientation predicted lower relationship security, lower global security, and more fearfulness.

Cowan & Mills (2004) found that having a higher orientation toward an external locus of control was the strongest predictor of hostile attitudes towards women. An external locus of control is associated with more perceptions of powerlessness and inadequacy. Further, the strongest individual correlate was that of intellectual intimacy. The more hostile men were towards women, the lower their intellectual intimacy was in relationships with women. Similarly, Costello et al. (2023) found that incels — “involuntarily celibate” men who share a “blackpill” ideology predictive of hostile sexism — have a higher external locus of control.

Attachment Styles

We tend to think of attachment styles as manifesting within an existing relationship dyad, but attachment also predicts initial romantic relationship formation. Poulsen et al. (2013) found that avoidant attachment, but not anxious attachment, predicted a lower likelihood of transition from dating into long-term relationships. In speed dating paradigms, anxious and avoidant attachment predicts less popularity; those who are more anxiously or avoidantly attached are selected less (Pepping et al., 2017; Tu et al. 2022). McClure & Lydon (2014) found that attachment anxiety predicted more negative assessment and outcomes when engaging in a 40-minute interaction with an attractive opposite-sex confederate researcher. Further, anxiously attached participants make fewer partner selections in a speed dating event and are rejected more for the selections that they do make (McClure et al., 2010). Consistent with this, Brumbaugh and Fraley (2002) found that securely attached individuals are preferred as mates over insecurely attached individuals.

Individuals with more secure attachment also tend to be more optimistic about dating (Carnelley & Janoff-Bulman, 1992) and experience less disillusionment toward dating (Liu et al., 2017). Anxious-ambivalent and avoidantly attached people also endorse more irrational beliefs about romantic relationships Stackert & Bursik (2003).

Anxiety

Mental illness, specifically in this context to anxiety, robustly predicts difficulty with intrapersonal interactions. This relationship may be further moderated by self-esteem and extraversion. Strugo and Muise (2019) found that those who were more apt to approach the opposite sex had more dating success and were likely to go on a second date whereas people more anxious and less extraverted had lower success due to feeling embarrassed and/or rejected. Schneier et al. (1994) found that higher anxiety predicted struggles with initial formation of relationships and the maintenance of long-term relationships. La Greca and Mackey (2007) found that this pattern may begin in adolescence; anxiety in adolescents who have fewer opposite-sex friends predicts future dating anxiety. More interactions with the opposite sex at a younger age can help reduce anxiety with the opposite sex. Adolescents may learn valuable social cues through experience while people who are more avoidant due to anxiety struggle to connect, acquire experience with early interpersonal interaction, and subsequently struggle in adult romantic relationships.

If anxiety does not limit dating contact or initial formation then it may nonetheless impair the health of relationships. Hanby et al. (2013) found that anxiety predicted more physical and psychological aggression in dating. Even when romantic relationships are able to be formed, the relationship may be more rocky from start to finish.

Depression

Along with anxiety, depression also predicts difficulties with dating. A potential moderator is substance abuse; depression is linked with higher substance use which in turn impairs relationship formation and success (Segrin et al., 2003). Lenton-Brym et al. (2021) found that anxiety and depression were both associated with motivation to use dating apps, as well as how one interacts with matches on dating apps. Nonetheless, even in the context of depression comorbid with substance abuse romantic relationships have a protective effect. Whitton et al. (2013) found in a large student sample that both men and women who were in relationships were happier, even if they struggled with alcohol abuse and depression.

Methods

We recruited 355 participants through a social media convenience / snowball sample.

A series of “Dating Difficulties” (DD) items were derived from 155 open-ended responses on social media and converted to 29 items. Dating Difficulties items were rated by participants on a 1 to 7 Likert scale. Items were coded into four categories (Self-Related difficulties, Other-Related difficulties, Interpersonal difficulties, and Circumstantial difficulties) by two researchers and total scores were summed for each category.

The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale-Short Form (ECR-S) (Wei et al., 2007) was used to assess attachment anxiety and avoidance. Rotter’s Locus Of Control Scale (Rotter, 1966) was used to assess internal and external LOC.

Mental health was assessed by binary self-report measures (YES/NO) for depression, anxiety, personality disorders, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Participants were first asked if they received a formal diagnosis and additionally if they believed that they had one of the above.

Participants self-rated their own physical attractiveness on a 1 to 7 Likert scale. We also collected responses on political identification, ethnicity, level of education, past and current relationship status, self-reported introversion and extroversion (as a binary variable), religiosity, drug use, and self-reported obesity.

The following hypotheses were preregistered (https://osf.io/7u4xk):

Locus Of Control:

H1.a – Higher ILOC predicts lower general dating difficulty.

H1.b – Lower ILOC predicts more other-oriented dating difficulty.

H1.c – Higher ILOC predicts more self-oriented dating difficulty.

Physical Attractiveness:

H2.a – Lower self-rated attractiveness predicts higher dating difficulty.

H2.b – Lower self-rated attractiveness predicts higher self-oriented dating difficulty.

Attachment Styles:

H3.a – Avoidant attachment predicts higher general dating difficulty.

H3.b – Anxious attachment predicts higher general dating difficulty.

Mental Health

H4.a – Self-assessed mental health predicts higher general dating difficulty.

H4.b – Diagnosed mental health predicts higher general dating difficulty.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

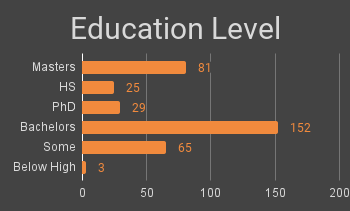

Below are charts with the demographics of the sample. Participants skewed toward an educated population with a relatively equal split between left and right political identification. 17.5% of the sample was female and 91% of the sample was heterosexual.

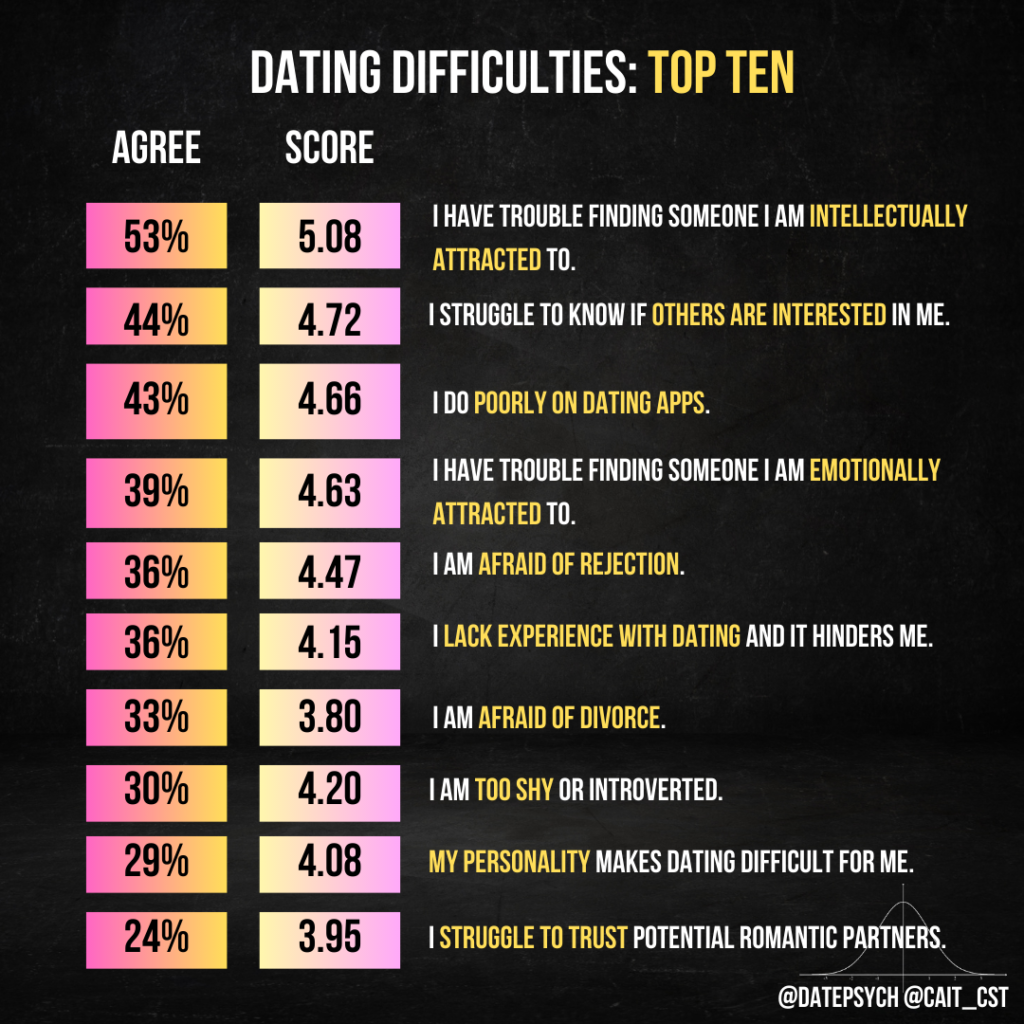

The Top Dating Difficulties

The following tables show the top dating difficulties for men and women. The first graphic shows the top ten dating difficulties rated by all participants. The subsequent four sections are ordered by Cohen’s d effect size and split by sex. The largest sex differences appear first. Percentages show participants who indicated strong agreement with the item (rated a 6 or a 7 on a 7 point Likert scale). Text tables show the mean scores and p-values for sex differences.

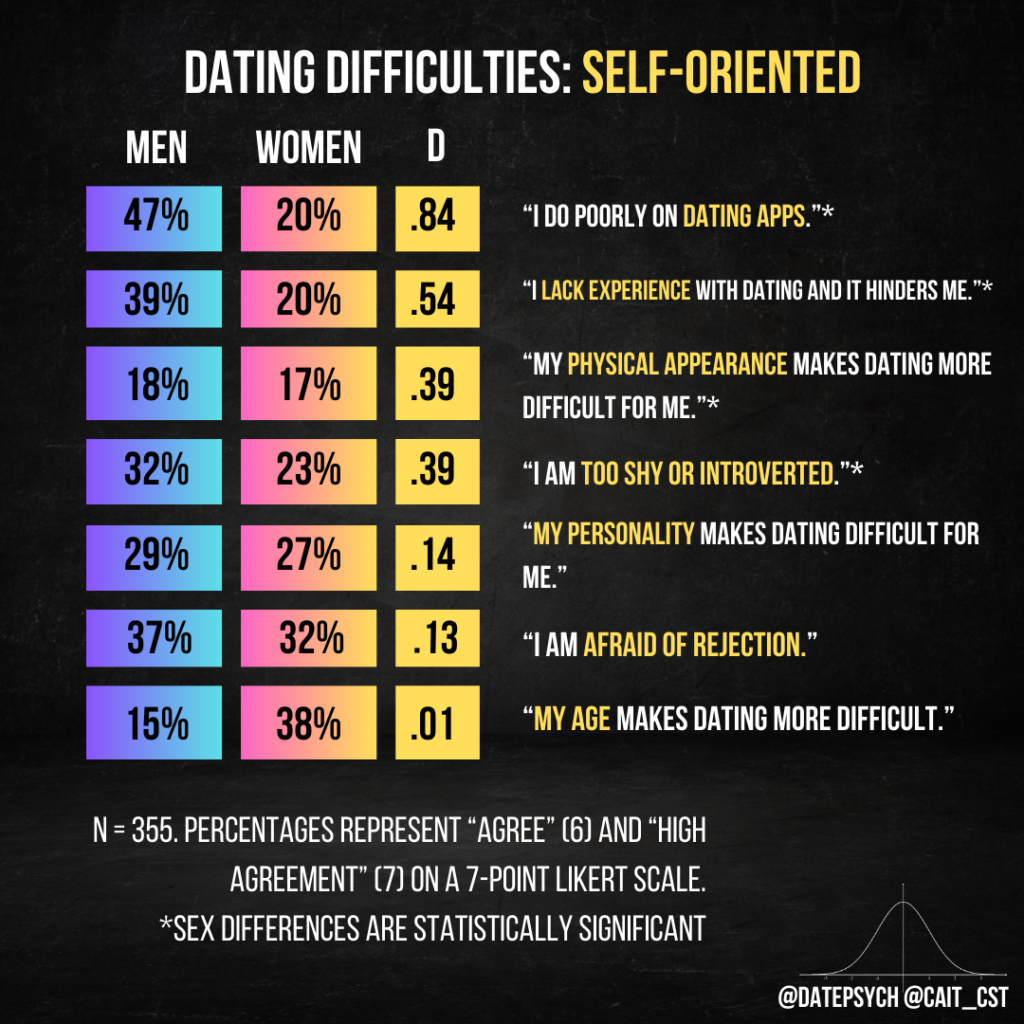

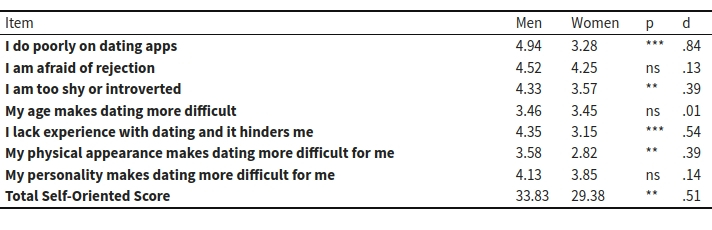

Self-Oriented or Personal Dating Difficulties

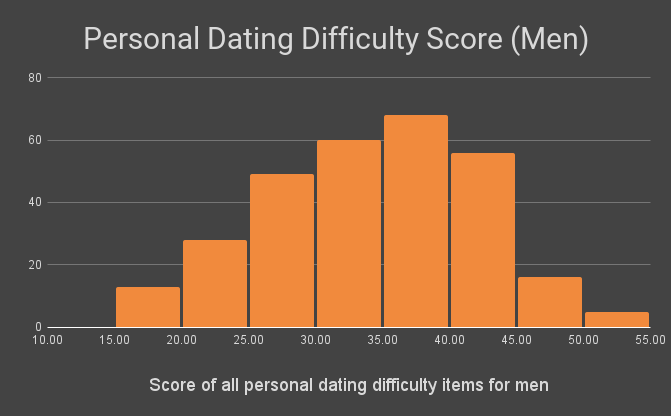

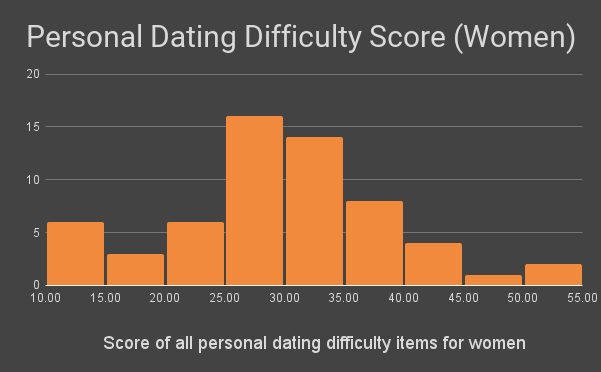

The following three charts show self-oriented dating difficulties. These items attribute dating difficulties to the self or the individual.

Men were significantly more likely to endorse self-oriented dating difficulties than women (d = .51, p = 0.001). Half of the male subsample reported agreement on difficulty with dating apps, more than twice as many as in the female subsample. Men were also more likely to endorse a lack of experience and concerns about their physical appearance as barriers to dating.

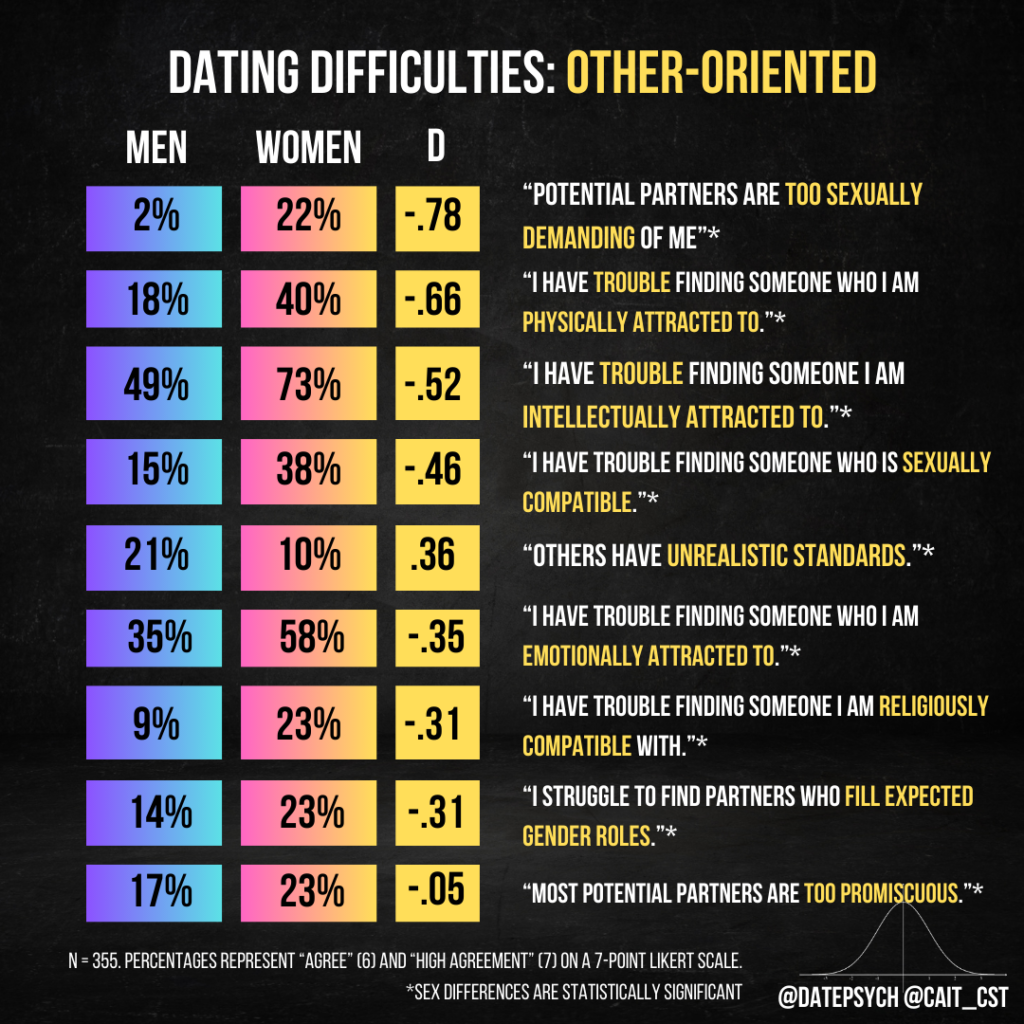

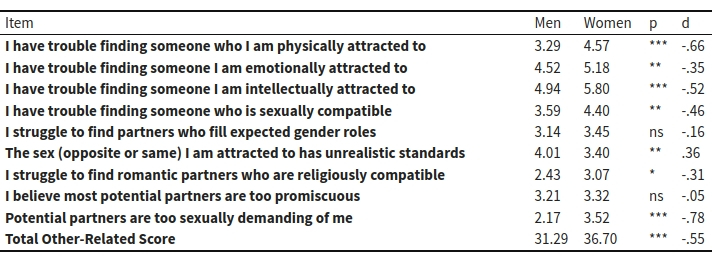

Other-Oriented Dating Difficulties

The following three charts show other-oriented dating difficulties. These items attribute difficulty to traits or characteristics in the behaviors of others in the mating pool.

Women were significantly more likely to endorse other-oriented dating difficulties than men (p < .001, d = -.55). For women, concerns that potential partners were too sexually demanding and difficulty finding partners they are physically attracted to topped the list. Women were also more likely to struggle to find someone they were emotionally or intellectually attracted to.

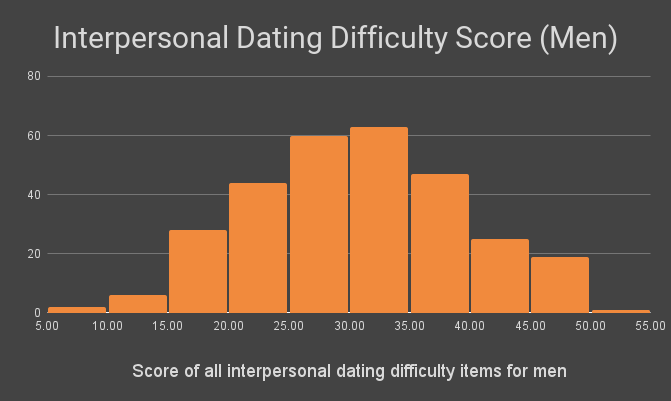

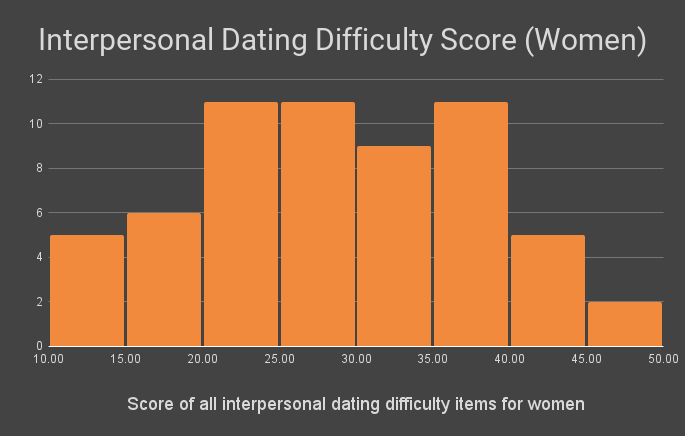

Interpersonal or Dyadic Dating Difficulty

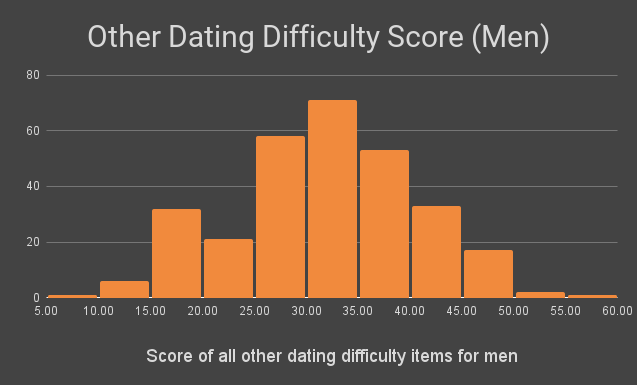

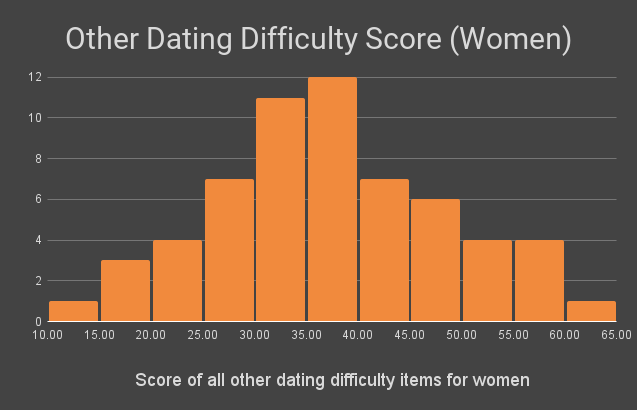

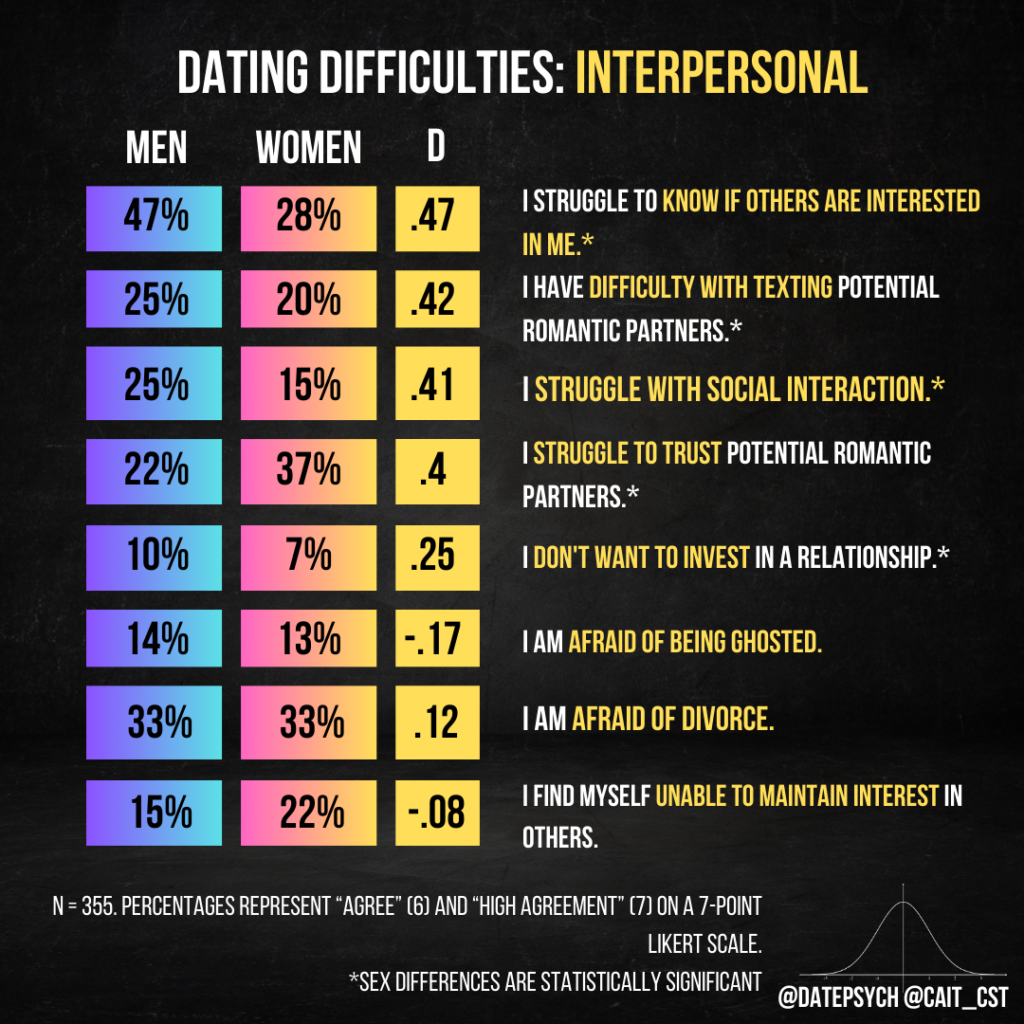

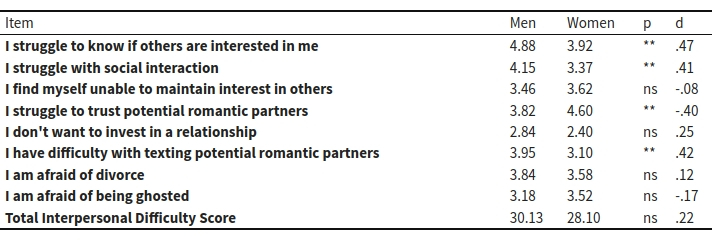

The following three charts show interpersonal dating difficulties. These items attribute dating difficulties to the interactions or outcomes that may occur within a dating context.

There was no sex difference for the total interpersonal dating difficulty score. However, men were more likely to struggle with social interaction, found it difficult to know if others were interested in them, and have difficulty texting. Women were more likely to struggle with trusting potential romantic partners.

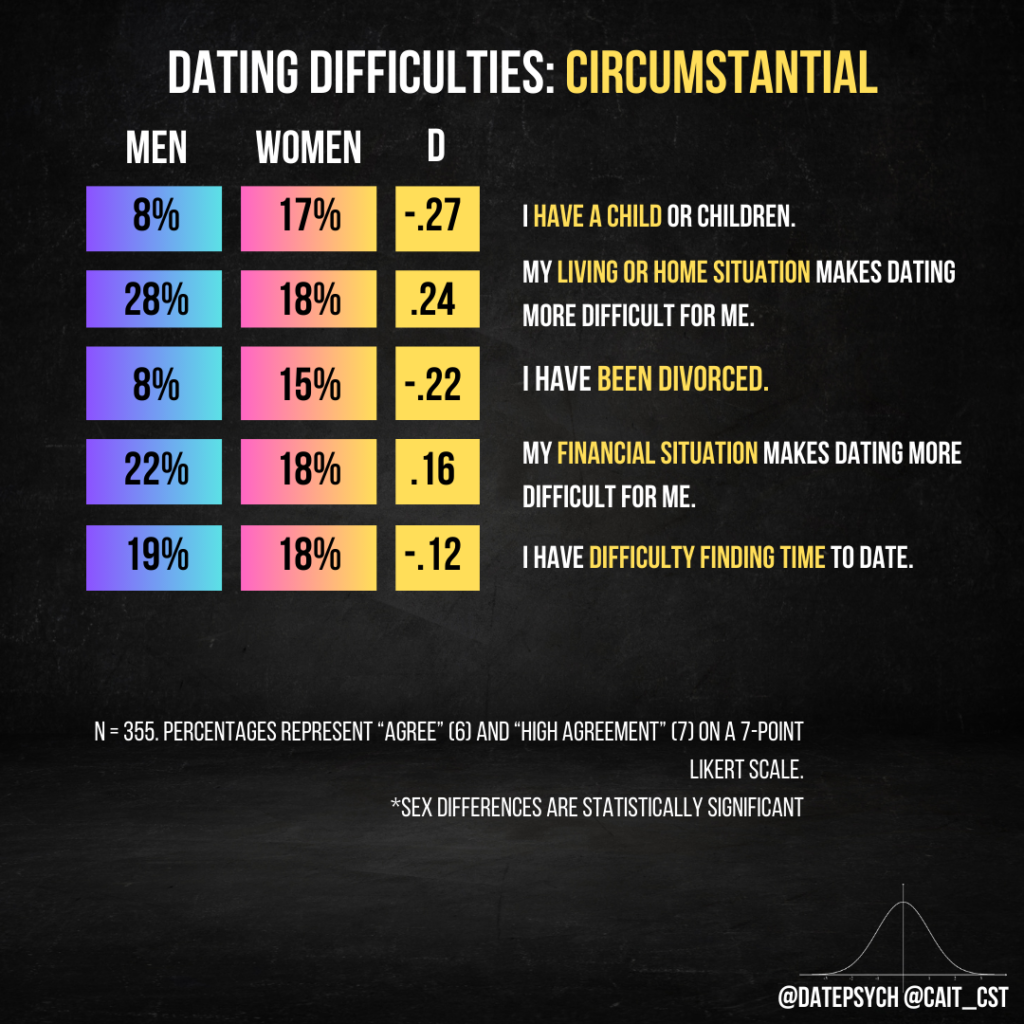

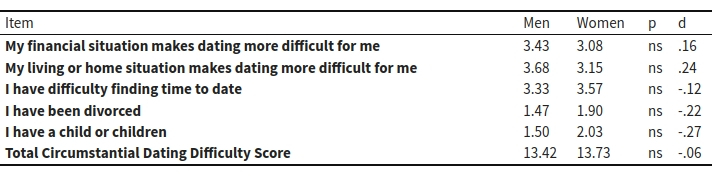

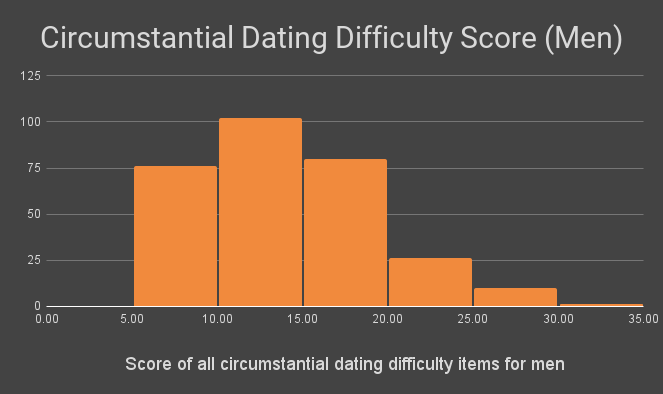

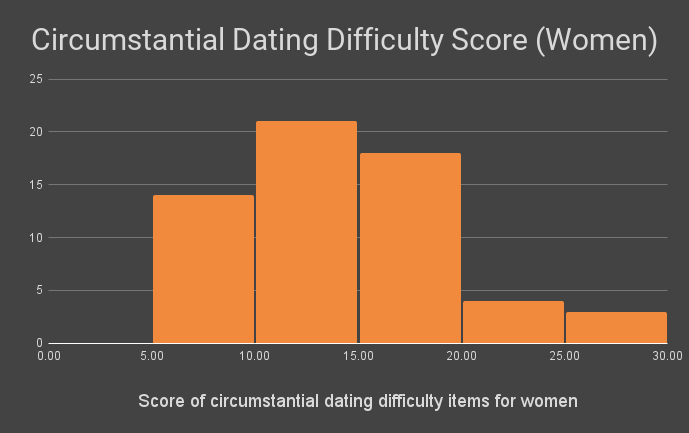

Circumstantial or Situational Dating Difficulty

The following three charts show circumstantial dating difficulties. These are items that attribute difficulty to the circumstances of the individual, situation, or environment.

For circumstantial dating difficulties, no significant sex differences were found.

Self-Reported vs Measured Dating Difficulty

A Pearson’s correlation was performed to assess the relationship between self-reported dating difficulty and dating difficulty measured as the total difficulty score of items. The results revealed a moderate to strong positive correlation (r = 0.48, p < 0.001) with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.398 to 0.558. Participants who believed dating was more difficult for them scored higher across dating difficulty items.

Past Sexual Partners and Dating Difficulty

Having fewer past sexual partners was associated with higher dating difficulty (p < .001, r = -.35). By sex, this was significant for men (p <.001, r = -.38), but not for women (p = 0.655, r = -.06).

Excluding men and women with zero past partners, the relationship remained significant for sexually active men (p < .001, r = -.33), but not for sexually active women (p = 0.837, r = -.03).

Restricting the range to 1-19 sexual partners, the relationship remained significant for men (p < .001, r = -.29), but was not significant for women.

Restricting the range to 1-9 sexual partners, the relationship remained significant for men p = .042, r = -.19) and became significant for women (p = 0.036, r = -.38). At a lower number of sexual partners, women reported a higher degree of dating difficulty within this range.

Individual Variables and Dating Difficulty

Monogamous/nonmonogamous status, alcohol use, recreational drug use, and religiosity did not predict higher total dating difficulty scores (all ps > .05).

Participants who indicated they were overweight or obese had higher total dating difficulty scores (M = 116) than those who did not (M = 107.2) (t(69.60) = 2.54, p < 0.01, 95% CI [1.92, 15.89], d = 0.39).

Participants who indicated they were extroverted rather than introverted had a lower total dating difficulty score (M = 97.5 vs M = 111.3) (t(112.7) = -4.94, p < 0.001, 95% CI [-19.25, -8.23], d = -0.64).

A one-way analysis of variance found that total dating difficulty scores were significantly different by education level (F(5, 349) = 4.602, p < .001). A Tukey post-hoc test revealed that participants with some college education (M = 119.6) had higher dating difficulty than participants with Bachelor’s or Master’s degrees (M = 104.5 and 106.7).

Locus Of Control

Participants who were unmarried or not in a committed relationship had a higher external locus of control (M = 12.95) than participants who were married or in a committed relationship (M = 11.75) (t(97.8) = -2.05, p = 0.043, 95% CI [-2.35, -0.03], d = -.28). Participants who have never been in a romantic relationship, however, did not have a higher external locus of control than the rest of the sample.

There was no significant sex difference in LOC scores (t(81.701) = -0.659, p = 0.512, two-tailed 95% CI [-1.712, 0.860], d = -0.095). Age also did not predict LOC scores (p = 0.941, r = -.004).

LOC scores were positively associated with total dating difficulty scores (p < .001, r = .27). This was true for both Other-Related dating difficulty (p < .001, r = 0.18) and Self-Related dating difficulty (p < .001, r = 0.26). LOC scores were also positively associated with Interpersonal dating difficulty (p < .001, r = 0.29) and Circumstantial dating difficulty (p = 0.011, r = .13). Individuals with a higher external locus of control reported more dating difficulty across the total score and each category.

When examining by sex, LOC predicted total dating difficulty for men (p < .001, r = .33) but not for women (p = 0.661, r = .06). Other-Related dating difficulty was significant for men (p = 0.001121, r = 0.1887978), but not for women (p = 0.267, r = 0.15). Self-Related dating difficulty was also significant for men (p < .001, r = 0.3), but not for women (p = 0.176, r = 0.18). Interpersonal dating difficulty was associated with a higher external locus of control for men (p < .001, r = .3), but not for women (p = 0.07, r = 0.24). Circumstantial dating difficulty was also associated with a higher external locus of control for men (p = 0.045, r = 0.12), but not for women (p = 0.079, r = 0.23).

LOC scores were negatively associated with self-rated physical attractiveness (p <.001, r = -.24). Participants with a higher external locus of control rated themselves as less attractive. When examined by sex, this relationship remained significant for men (p < .001, r = -.29), but not for women (p = 0.569, r = -.075).

LOC scores were positively associated with both anxious (p < .001, r = 0.19) and avoidant (p <.001, r = 0.19) attachment. Participants with a higher external locus of control were higher in anxious and avoidant attachment on average.

Individual Variables and LOC

Locus of control was not associated with monogamy/nonmonogamy, overweight/obese status, alcohol use, drug use, religiosity, or introversion/extroversion (all ps > .05). Locus of control was associated with education status; a one-way analysis of variance found a significant effect on locus of control, (F(5, 349) = 2.962, p = 0.012). A Tukey post-hoc test revealed significant differences only for participants with a level of education below high school level when contrasted with high school graduates, some college, and college graduates (Bachelor’s, Master’s, and PhD or Professional Degree). For ethnicity, the results revealed no significant association with locus of control (F(4, 350) = 1.682, p = 0.154).

Attractiveness

We found a significant sex difference in self-rated physical attractiveness where women rated themselves as more attractive (M = 5.02) than men rated themselves (M = 4.52) (t(82.39) = -2.726, p = 0.008, two-tailed 95% CI [-0.867, -0.136], d = -0.392).

Lower self-rated physical attractiveness predicted higher dating difficulty across all items (p < .001, r = -.31) and Self-Related dating difficulty (p < .001, r = -.38). Self-rated physical attractiveness did not predict Other-Related dating difficulty (p = .254, r = .06) nor Circumstantial dating difficulty (p = 0.916, r = .01), but did predict Interpersonal dating difficulty (p < .001, r = -.21). Participants who believed themselves to be less physically attractive attributed dating difficulties to themselves and to their potential dyadic interactions, but did not externalize dating difficulties to others or the circumstances at hand.

This relationship again was driven by male participants. Men lower in self-assessed physical attractiveness had higher dating difficulty total scores (p <.001, r = -.29), but the relationship between self-assessed physical attractiveness and dating difficulty was not significant for women (p = .569, r = .075). A significant relationship was found for self-assessed physical attractiveness across all four dating difficulties categories for men (all ps < .05, r = .11 to .30). For women, associations were not significant within any of the four categories.

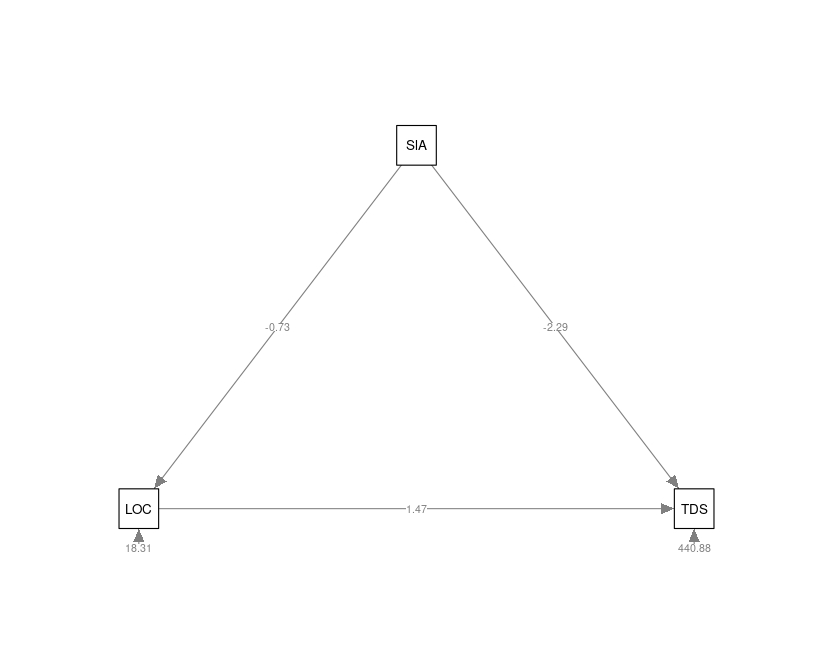

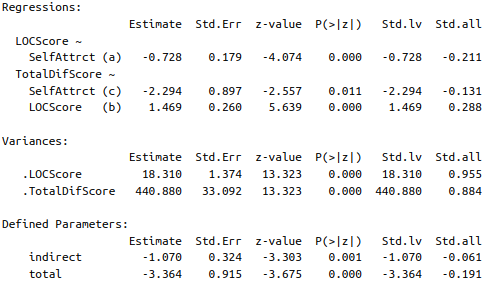

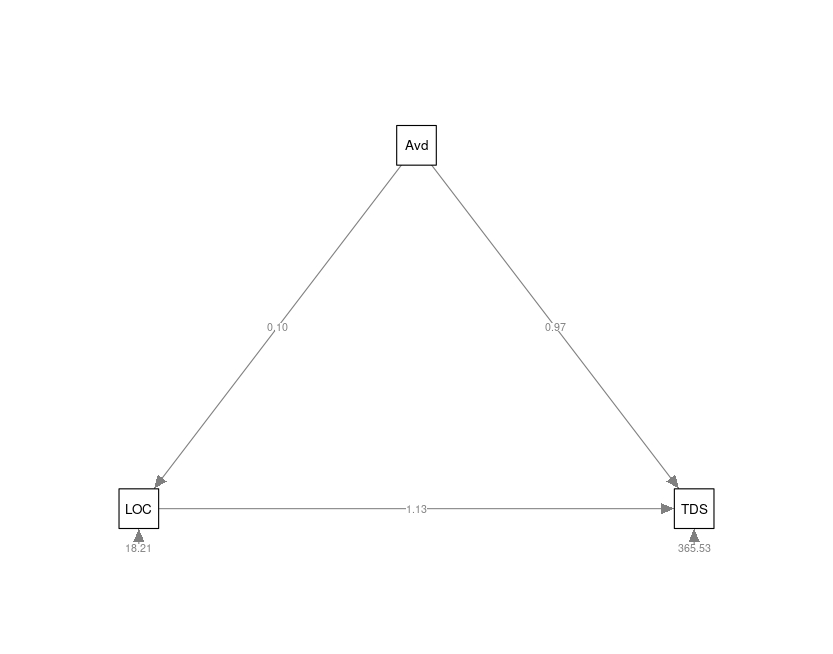

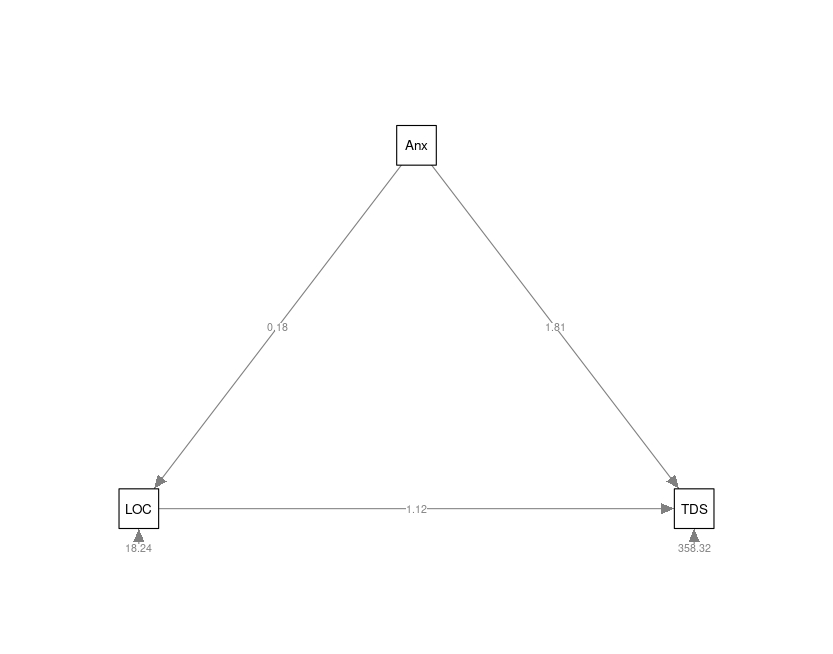

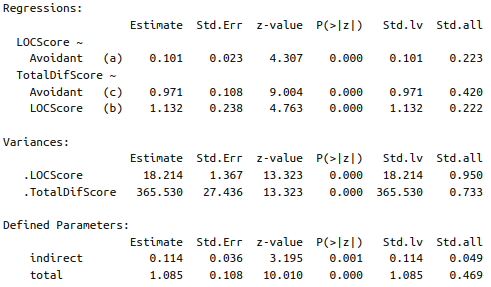

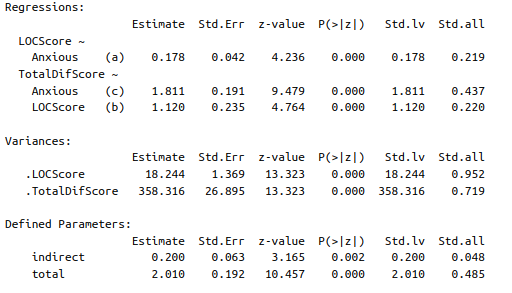

As locus of control was correlated with both self-assessed physical attractiveness and total dating difficulty, we performed a mediation analysis with locus of control as an indirect pathway.

Although a substantial amount of variance was unexplained by the model, the relationship between self-rated physical attractiveness and total dating difficulty was moderated by locus of control.

Attachment Styles

There was a negative correlation with the number of past sexual partners and insecure attachment styles. Participants with more sexual partners scored lower in anxious (p = .016, r = -.13) and avoidant (p =.031, r = -.11) attachment.

There were positive correlations with avoidant and anxious attachment on both self-rated dating difficulty and the total dating difficulty scores. Avoidant attachment predicted higher self-rated dating difficulty (p < .001, r = .24) and higher total dating difficulty scores (p < .001, r = .45). Anxious attachment also predicted higher self-rated dating difficulty (p < .001, r = .26) and higher total dating difficulty scores (p < .001, r = .47).

As locus of control and attachment styles predicted higher dating difficulty, a mediation analysis was performed to determine if locus of control may act as a mediator for the relationship between attachment styles and dating difficulty.

Only a small portion of the variance was explained by locus of control as a mediator of attachment style on total dating difficulty.

Mental Health and Dating Difficulty

Participants who believed they may have anxiety (M = 5.5) had higher self-rated dating difficulty than those who did not (M = 4.8) (t(315.27) = 3.73, p < .001, 95% CI [0.32, 1.04], d = .40). Participants who believed they may have anxiety (M = 114.6) also had higher total dating difficulty scores than those who did not (M = 101.9) (t(343.31) = 5.89, p < .001, 95% CI [8.92, 17.86], d = 0.63).

Having received a diagnosis for an anxiety disorder did predict higher self-rated dating difficulty (t(99.26) = 1.33, p = 0.19, 95% CI [-0.14, 0.70], d = 0.18)). However, participants who reported they received an anxiety diagnosis (M = 117.5) did have higher total dating difficulty scores than those who did not (M = 106.7) (t(86.1) = 3.52, p < .001, 95% CI [4.70, 16.90], d = 0.49).

Self-assessed depression (M = 5.8) was associated with higher self-reported dating difficulty when compared with participants who did not believe they were depressed (M = 4.8) (t(306.91) = 5.59, p < .001, 95% CI [0.63, 1.31], d = 0.60). Additionally, participants who believed they were depressed (M = 116.5) had higher total dating difficulty scores than those who did not (M = 104) (t(253.54) = 5.14, p < .001, 95% CI [7.68, 17.21], d = 0.57).

Participants who indicated they received a diagnosis of depression (M = 5.5) had higher self-reported dating difficulty than participants who did not (M = 5.1) (t(151.44) = 1.98, p = 0.04, 95% CI [0.00, 0.79], d = 0.24). Total dating difficulty scores were also higher for participants who received a depression diagnosis (M = 116.7) than for those who did not (M = 106) (t(136.13) = 3.86, p < .001, 95% CI [5.18, 16.05], d = 0.48).

Participants who believed they had a personality disorder did not have significantly higher self-reported dating difficulty (t(59.67) = 1.73, p = 0.09, 95% CI [-0.07, 0.93], d = 0.26). However, participants who believed they had a personality disorder did have higher total dating difficulty scores (M = 120.9) than those who did not (M = 106.8) (t(53.18) = 3.69, p < .001, 95% CI [6.45, 21.84], d = 0.62).

Participants who indicated they were diagnosed with a personality disorder did not have higher self-reported dating difficulty (t(12.84) = 0.29, p = 0.78, 95% CI [-0.95, 1.24], d = 0.08) nor higher dating difficulty as assessed by the total dating difficulty score (t(12.56) = 1.84, p = 0.09, 95% CI [-2.57, 31.79], d = 0.58).

Mental Health and LOC

Individuals with self-assessed anxiety (p < .001, d = .46) and depression (p < .001, d = .53) had a higher external locus of control. However, having had a diagnosis of anxiety or depression did not result in significantly different locus of control scores (all ps > .05). Diagnoses of anxiety, depression, personality disorders, as well as self-assessment of personality disorders, was not associated with locus of control scores (all ps > .05).

Result Summary

- Men were more likely to endorse self-oriented dating difficulties while women were more likely to endorse other-oriented dating difficulties. There were no sex differences for total interpersonal or total dating difficulty scores. However, across the board, men and women endorsed different dating difficulties with high frequency. Men and women share many dating difficulties, but sex differences in the frequency of dating difficulty endorsement abound.

- There were no sex or age differences in locus of control. LOC may not explain sex differences in perceptions of dating difficulty.

- Locus of control was a significant predictor of dating difficulties across categories with small-to-medium effect sizes — for men. Locus of control did not predict dating difficulties for women.

- Participants who were married or in a committed relationship were less likely to have an external locus of control than single participants. However, participants who had never been in a romantic relationship were not more likely to have an external locus of control.

- Attachment styles (anxious and avoidant) predicted both self-rated dating difficulty and higher total dating difficulty scores with medium-to-large effects.

- Locus of control was associated with both anxious and avoidant attachment; participants higher in anxious or avoidant attachment had a higher external locus of control.

- However, locus of control may not be a strong moderator for effects of attachment style on dating difficulties.

- Mental health items (depression, anxiety, and personality disorders), both self-assessed or diagnosed, predicted self-rated dating difficulty across most conditions and higher total dating difficulty across all items.

- A higher external locus of control was associated with participant perceptions that they may have anxiety or depression. However, locus of control did not predict differences across mental health diagnoses or self-assessments of having a personality disorder.

- Being obese or overweight was associated with higher dating difficulty, as was self-reported introversion over self-reported extroversion.

- Bachelor’s and Master’s degree holders had less dating difficulty than “some college” participants.

- Men and women with more past sexual partners had lower dating difficulty scores.

- Self-rated physical attractiveness (low) was associated with a higher external locus of control and with higher total dating difficulty scores.

Discussion

Why is locus of control predictive of dating difficulty for men, but not for women? We can’t rule out that the sample was underpowered to detect significant effects for women. However, locus of control may be more important for men given sex roles in dating dynamics. Men are expected to approach women, plan dates, and initiate first sexual contact (e.g. a first kiss). Men who are less agentic in dating behavior may experience more difficulty throughout the process. Men also have a more autocratic leadership style and may take this role in interpersonal relationships. If something goes wrong men may learn to blame external forces. Women, on the other hand, may lack this form of pressure when it comes to making early dating decisions.

Men who rated themselves lower in physical attractiveness had a higher external locus of control. This may be because individuals lower in physical attractiveness have a history of less successful dating experiences and lack the positive feedback that comes from successful dating outcomes. Men may also experience challenges that truly are out of their control in ways that women do not when it comes to dating, particularly in the context of one’s physical appearance. For example, men experience strong pressures to be tall, have a full head of hair, and to be muscular. These all have a substantial genetic contribution, as does facial attractiveness, in ways that other forms of beauty enhancement (e.g. makeup use or body hair removal) may not. Men may also be less particular about traits of low malleability in women and more willing to compromise in mate selection. The self-perception of oneself as unattractive — and in particular unattractive due to forces beyond control of the individual — may shape a worldview characterized by lower agency.

Women reported significantly more difficulty finding someone intellectually attractive and also feeling like there are more physical demands early on in dating. These were the top two items endorsed by women. A common experience of women is the perception that men seek out sex earlier in dating. This may impede women from feeling the emotional connection women desire before having sex. Similarly, women reported significantly more difficulty finding someone who was sexually compatible and someone who was physically attractive. Women are more selective in mates, particularly for sexual access, and score substantially lower in sociosexuality on average. A mismatch may occur where men seek out early sexual access that is undesired by women. Men may desire sex early in a relationship, both as a goal in itself and as a form of commitment or emotional connection. Women, on the other hand, must screen out potential partners who are unwilling to invest. The desire held by women to connect and bond with a potential partner and the desire men have for early sexual access may run at odds with one another.

While physical attractiveness is important to both sexes, men value physical attractiveness often to the exclusion of other traits. Meanwhile, women place a higher value upon intellectual and emotional connection than men do. Men indicated significantly more that they had a hard time gauging a woman’s interest in them. This is consistent with past research, which indicates that men gauge interest poorly and often overestimate sexual interest. An external locus of control may also correspond with difficulty in reading social cues. Men may lack awareness of what women like in the moment or if women feel safe on a date. Men may also not perceive when a woman doesn’t reciprocate interest and fail to pick up on positive body language. When a woman doesn’t want to go out on another date, a man may blame her or other external factors rather than looking inward to his own behavior as precipitating the disinterest. Without an awareness of this feedback men may be unable to change their behaviors, making it difficult on subsequent dates as the same behavior is repeated.

A higher external locus of control was associated with both anxious and avoidant attachment. Insecure attachment styles are robust predictors of poor relationship outcomes. Further, theory on attachment styles posits that these develop through early childhood experiences with a primary caregiver. It may be that a higher frequency of negative experiences in past relationships drive the formation of an external locus of control. Early caregiving experiences are largely out of control of the child and children may begin to ascribe interpersonal relationship outcomes to external forces. The world may seem out of one’s control and future relationships may come to be perceived as if the other person is unable to be depended upon.

However, our mediation analysis found only a small portion of the variance in dating difficulty was moderated by locus of control. Although locus of control and insecure attachment styles are correlated, the two may impact dating difficulty through different pathways.

Mental health was associated with more dating difficulty and a higher external locus of control across most items. Interestingly, self-assessed but not diagnosed mental health issues were more consistently associated with an external locus of control. This may be because individuals with mental health problems and a higher internal locus of control are more likely to seek out professional help. Conversely, an external locus of control may lead one to feel as if mental health issues are beyond help. They may be less agentic in seeking out the help that they need.

We found no difference in locus of control scores by age. Recent research has examined if the youngest adults, Zoomers, are psychologically different in traits related to risk aversion that may explain poorer dating outcomes. Locus of control might represent another generational shift that impacts dating difficulty in young adults. Although the current data don’t show a generational difference, cross-sectional data is not apt for drawing a conclusion and this may be examined in the future with longitudinal data.

Conclusion

Low self-perceptions of physical attractiveness, an external locus of control, poor mental health, and insecure attachment styles all predicted higher endorsement of dating difficulty. Further, many of these items were correlated with one another. Future research might explore how interactions between these variables produce poorer dating outcomes for individuals. Difficulty in dating may come through different pathways, but it seems to be the case that what produces difficulty in finding romantic relationships clusters together. It’s rarely just one thing, but rather the “perfect storm” of traits and dispositions that may keep someone perpetually single.

References

Abramova, O., Baumann, A., Krasnova, H., & Buxmann, P. (2016, January). Gender differences in online dating: What do we know so far? A systematic literature review. In 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS) (pp. 3858-3867). IEEE.

Asendorpf, J. B., Penke, L., & Back, M. D. (2011). From dating to mating and relating: Predictors of initial and long–term outcomes of speed–dating in a community sample. European Journal of Personality, 25(1), 16-30.

Atkins, S. (2019). Online Dating Versus Face-to-Face Dating: A Comparison of Attachment Style and Relationship Success (Doctoral dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology).

Back, M. D., Penke, L., Schmukle, S. C., Sachse, K., Borkenau, P., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2011). Why mate choices are not as reciprocal as we assume: The role of personality, flirting and physical attractiveness. European Journal of Personality, 25(2), 120-132.

Bringle, R. G. (1981). Conceptualizing jealousy as a disposition. Alternative Lifestyles, 4, 274-290.

Brumbaugh, C. C., & Fraley, R. C. (2010). Adult attachment and dating strategies: How do insecure people attract mates?. Personal Relationships, 17(4), 599-614.

Canary, D. J., Cunningham, E. M., & Cody, M. J. (1988). Goal types, gender, and locus of control in managing interpersonal conflict. Communication Research, 15(4), 426-446.

Carnelley, K. B., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1992). Optimism about love relationships: General vs specific lessons from one’s personal experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 9(1), 5-20.

Caughlin, J. P., & Vangelisti, A. L. (2000). An individual difference explanation of why married couples engage in the demand/withdraw pattern of conflict. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17(4-5), 523-551.

Chorney, D. B., & Morris, T. L. (2008). The changing face of dating anxiety: Issues in assessment with special populations. Clinical psychology: science and practice, 15(3), 224.

Çırakoğlu, O. C. (2006). Role of locus of control and critical thinking in handling dissatisfaction in romantic relationships of university students.

Costello, W., Rolon, V., Thomas, A. G., & Schmitt, D. P. (2023). The mating psychology of incels (involuntary celibates): misfortunes, misperceptions, and misrepresentations. The Journal of Sex Research, 1-12.

Cowan, G., & Mills, R. D. (2004). Personal inadequacy and intimacy predictors of men’s hostility toward women. Sex Roles, 51, 67-78.

Dion, K. L., & Dion, K. K. (1973). Correlates of romantic love. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 41(1), 51.

Eastwick, P. W., Eagly, A. H., Finkel, E. J., & Johnson, S. E. (2011). Implicit and explicit preferences for physical attractiveness in a romantic partner: a double dissociation in predictive validity. Journal of personality and social psychology, 101(5), 993.

Eastwick, P. W., & Finkel, E. J. (2008). Sex differences in mate preferences revisited: Do people know what they initially desire in a romantic partner?. Journal of personality and social psychology, 94(2), 245.

Hanby, M. S., Fales, J., Nangle, D. W., Serwik, A. K., & Hedrich, U. J. (2012). Social anxiety as a predictor of dating aggression. Journal of Interpersonal violence, 27(10), 1867-1888.

Jones, J. T., & Cunningham, J. D. (1996). Attachment styles and other predictors of relationship satisfaction in dating couples. Personal Relationships, 3(4), 387-399.

Kim, M., Kwon, K. N., & Lee, M. (2009). Psychological characteristics of Internet dating service users: The effect of self-esteem, involvement, and sociability on the use of Internet dating services. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12(4), 445-449.

La Greca, A. M., & Mackey, E. R. (2007). Adolescents’ anxiety in dating situations: The potential role of friends and romantic partners. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36(4), 522-533.

Leak, G. K., & Cooney, R. R. (2001). Self-determination, attachment styles, and well-being in adult romantic relationships. Representative Research in Social Psychology, 25, 55-62.

Lenton-Brym, A. P., Santiago, V. A., Fredborg, B. K., & Antony, M. M. (2021). Associations between social anxiety, depression, and use of mobile dating applications. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(2), 86-93.

Liu, J., Wang, Y., & Jackson, T. (2017). Towards explaining relationship dissatisfaction in Chinese dating couples: Relationship disillusionment, emergent distress, or insecure attachment style?. Personality and Individual Differences, 112, 42-48.

Lumpkin, J. R. (1986). The relationship between locus of control and age: New evidence. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 1(2), 245.

Luo, S., & Zhang, G. (2009). What leads to romantic attraction: Similarity, reciprocity, security, or beauty? Evidence from a speed‐dating study. Journal of personality, 77(4), 933-964.

McClure, M. J., Lydon, J. E., Baccus, J. R., & Baldwin, M. W. (2010). A signal detection analysis of chronic attachment anxiety at speed dating: Being unpopular is only the first part of the problem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(8), 1024-1036.

McMahon, B. (2007). Organizational commitment, relationship commitment and their association with attachment style and locus of control.

Mickelson, K. D., Kessler, R. C., & Shaver, P. R. (1997). Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. Journal of personality and social psychology, 73(5), 1092.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2005). Attachment theory and emotions in close relationships: Exploring the attachment‐related dynamics of emotional reactions to relational events. Personal relationships, 12(2), 149-168.

Miller, P. C., Lefcourt, H. M., Holmes, J. G., Ware, E. E., & Saleh, W. E. (1986). Marital locus of control and marital problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(1), 161.

Mole, M. L. (2013). Satisfaction in adult romantic relationships after parental divorce: the role of locus of control.

Moongrove, D. S. (1995). A study of attitudes toward romantic love in females, in relationship to locus of control and feminist activism. New School for Social Research.

Morry, M. M. (2003). Perceived locus of control and satisfaction in same–sex friendships. Personal Relationships, 10(4), 495-509.

Munro, B. E., & Adams, G. R. (1978). Correlates of romantic love revisited. The Journal of Psychology, 98(2), 211-214.

Poulsen, F. O., Holman, T. B., Busby, D. M., & Carroll, J. S. (2013). Physical attraction, attachment styles, and dating development. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(3), 301-319.

Poulsen, F. O., Holman, T. B., Busby, D. M., & Carroll, J. S. (2013). Physical attraction, attachment styles, and dating development. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(3), 301-319.

Prager, K. J. (1986). Intimacy status: Its relationship to locus of control, self-disclosure, and anxiety in adults. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12(1), 91-109.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 80(1), 1.

Schneier, F. R., Heckelman, L. R., Garfinkel, R., Campeas, R., Fallon, B. A., Gitow, A., … & Liebowitz, M. R. (1994). Functional impairment in social phobia. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 55(8), 322-331.

Segrin, C., Powell, H. L., Givertz, M., & Brackin, A. (2003). Symptoms of depression, relational quality, and loneliness in dating relationships. Personal Relationships, 10(1), 25-36.

Simpson, J. A. (1990). Influence of attachment styles on romantic relationships. Journal of personality and social psychology, 59(5), 971.

Stackert, R. A., & Bursik, K. (2003). Why am I unsatisfied? Adult attachment style, gendered irrational relationship beliefs, and young adult romantic relationship satisfaction. Personality and individual differences, 34(8), 1419-1429.

Thomas, E. L. (2009). The interrelationships between adult attachment style, commitment, frequency of, variety, and motivation for sexual behaviors in non-married, dating relationships (Doctoral dissertation, Northern Illinois University).

Tu, E., Maxwell, J. A., Kim, J. J., Peragine, D., Impett, E. A., & Muise, A. (2022). Is my attachment style showing? Perceptions of a date’s attachment anxiety and avoidance and dating interest during a speed-dating event. Journal of Research in Personality, 100, 104269.

Walster, E., Aronson, V., Abrahams, D., & Rottman, L. (1966). Importance of physical attractiveness in dating behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology, 4(5), 508.

Wei, M., Russell, D. W., Mallinckrodt, B., & Vogel, D. L. (2007). The experiences in Close

Relationship Scale (ECR)-Short Form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of

Personality Assessment, 88, 187-204.

Whitton, S. W., Weitbrecht, E. M., Kuryluk, A. D., & Bruner, M. R. (2013). Committed dating relationships and mental health among college students. Journal of American college health, 61(3), 176-183.

4 comments

Nothing like a good reading/watching of Alex’s blog/videos to spend a whole night staring at the ceiling contemplating suicide.

What happened to you bro are you ok?