Mate Value and Attitudes Toward Promiscuity

Past research has found that individual mating experiences, as well as male mate value, predict men’s attitudes toward sexual behavior. In one experimental study (Luberti et al., 2022), men recorded a video of themselves and were assigned to receive positive or negative romantic feedback from female raters. Men who received negative feedback from women shifted their attitudes and became less supportive of casual sex. Further, this effect was mediated by trait mate value, such that it only acted upon men of low or average mate value. In other words, when men feel like they are not closer to the top of the mating hierarchy and they also receive congruent feedback from women, they become less supportive of casual sex.

In a second experimental study (Surbey & Brice, 2007), participants estimated their own mate value and also indicated their own preferred sexual strategy. Men were then assigned to conditions where they received fictitious feedback on their own value as a mate, with one group receiving negative feedback and one group receiving positive feedback. Male participants who received positive feedback shifted their preferred sexual strategy to a higher endorsement of casual sex (with a large effect size: η2 = .29). In other words, when men were made to believe that they had higher mate value, they supported casual sex more. Baseline self-perceived mate value was also associated with support for casual sex. Men who believed they had higher mate value at the outset endorsed short-term mating strategies more.

Imbalanced sex ratios, or the perception thereof, also produce this effect. When men believe there are fewer available mates, or that there is more male competition, they support casual sex less (Arnocky et al., 2014; Gouda-Vossos et al., 2023). Fewer perceived sexual options and higher perceived risks of losing mates to rivals shift male attitudes away from promiscuity.

These are likely to be intuitive results to you. The same phenomenon manifests consistently in non-sexual domains. You have probably experienced it in the wild. It is the sour grapes effect, as old as Aesop, and as such it is literally “common sense.” It is a collective tidbit of our folk wisdom and fables that, at least in this case, turns out to be true. Nietzsche observed the same in The Genealogy of Morality. The life-affirming masters loved to drink, fight, and fuck. Slave morality emerged as a negation of the masters. When people want something that they cannot have they begin to resent it, develop negative attitudes toward it, and try to restrict it.

Peter DeScioli (2023) expounded on the evolutionary rationale for this. We adopt moral attitudes on sexuality that favor “our side” and benefit our individual sexual strategies. Men who struggle to attract women may develop hostility toward men who they perceive as more successful with other women. One narrative of “Chad” in incel communities depicts Chad as a man who monopolizes other women, removing those women from the mating market. In more traditional eras, with socially enforced monogamy, some incels believe they would have had a better chance at finding a wife. At the extreme tails of incel discourse, it isn’t uncommon to read incel revenge fantasies that involve harming Chad. This is the oldest form of intrasexual competition, physical violence. (That said, I will reiterate once again, incels statistically pose a very low risk of actual violence (Costello & Buss, 2023) despite the occasional sabre-rattling.) Men who benefit from a sexually libertine marketplace will be more supportive of it, because it facilitates access to sex for them. Men who are more fearful of infidelity or divorce will support norms and laws that restrict and punish unfaithfulness. Men who can or might steal your girlfriend won’t support these norms as much, because those norms would be an imposition on their preferred mating strategies.

Sexual Deprivation and Hostility

Frustrated mating is also associated with negative attitudes toward women. Unwanted celibacy predicts hostile attitudes toward women (Grunau et al., 2022; Hamilton, 2022). Across five studies, men who felt subjectively disadvantaged in life exhibited more hostile sexism toward women (Teng et al., 2022). A recent study found a curvilinear relationship with sexual success and misogyny, such that men with the highest and lowest numbers of past sexual partners were lower in misogynistic attitudes (Zhang et al., 2024). Bosson et al. (2022) found that mate value mediated associations with hostile and benevolent sexism. Men low in mate value expressed high hostile, but low benevolent, sexism. In my own research, men who scored high on a measure of romantic success and physical attractiveness scored substantially lower on the Extreme Misogyny Scale (EMS).

Evolutionary psychologist Andrew Thomas created a model that explains what is going on here. It’s a sort of downward spiral:

Lankford (2021) has also proposed a sexual frustration theory that explains how a deprivation of sexual fulfillment contributes to crime, violence, and antisocial behavior. Building on an abundance of past research showing associations (and causal relationships) between emotional frustration and hostility, Lankford noted that sexual frustration and sexual deprivation produce similar outcomes. Two specific expressions of sexual frustration are power-seeking and revenge-seeking. The sexually frustrated may seek to gain power over those they are frustrated with. A desire to restrict the sexual behaviors of others may be one way some individuals choose to seek revenge and impose power, among others.

Sexual Risk Taking

Sexual risk taking is associated with having a larger number of past sexual partners. For example, more promiscuous individuals are less likely to regularly use condoms, more likely to have sex under the influence of substances, and are less concerned about contracting sexually transmitted diseases or infections (STDs / STIs). Individuals who are more risk-averse may suffer for that risk aversion on the sexual marketplace.

The spectrum of risk tolerance is a stable trait: people who avoid risk in one domain tend to avoid risk in others. Men who are sexually risk averse are also more socially risk averse. In my research, men who were higher in trait risk aversion were less likely to have asked a woman on a date in the past year. Involuntarily celibate men were also more risk averse. Further, risk aversion is associated with higher disgust sensitivity (Sevi et al., 2021).

Negative attitudes toward promiscuity, as well as a desire to limit promiscuity, may reflect a desire to limit risk. This may be the risk of female defection from a relationship. For example, taboos on infidelity may prevent cuckoldry, so we may expect men at greater risk of (or who have greater anxieties over) cuckoldry to support stronger social sanctions on infidelity. The desire to limit risk may also reflect lower disgust sensitivity, or the avoidance of pathogen risk.

Current Research

Given this background, the current research will examine relationships between frustrated mating, attitudes toward promiscuity (individual and social), sexual risk-taking, and perceptions of extrapair defection risk.

Methods & Scales

Participants (N = 284; 75% Male) were recruited as a convenience sample from social media. The mean age of the sample was 33.7 (SD = 10.4). 60.6% of participants were neither married nor in a committed relationship. 28.2% of participants responded affirmatively to the statement, “I have not had sex in the past two years and I would like to.”

Scales and Items

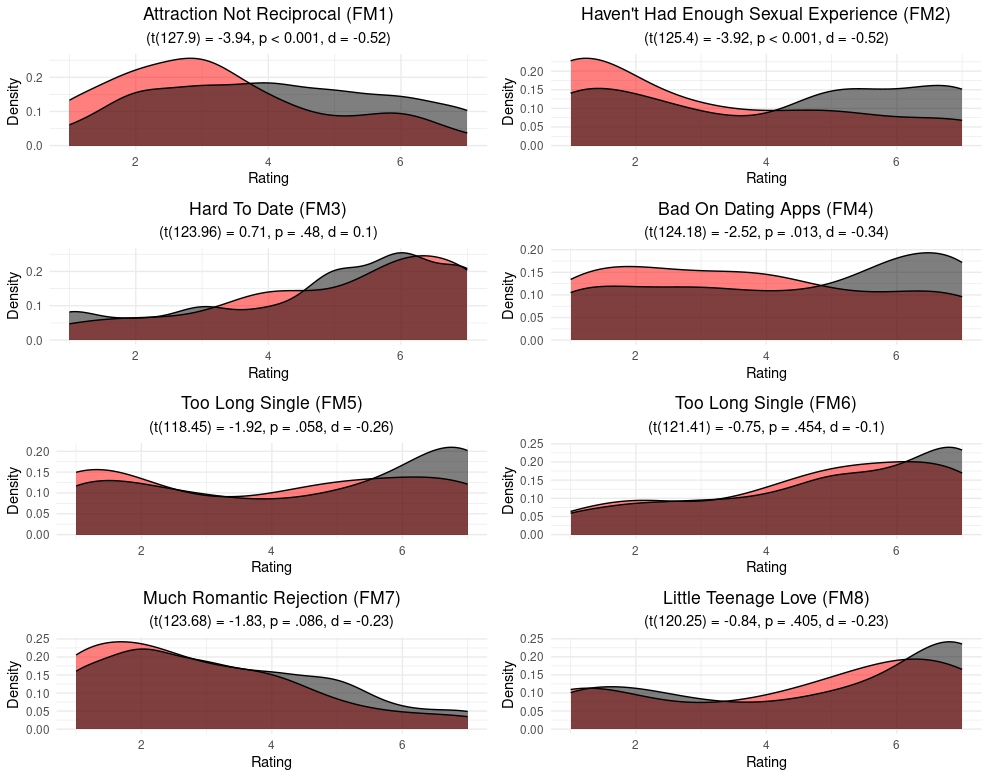

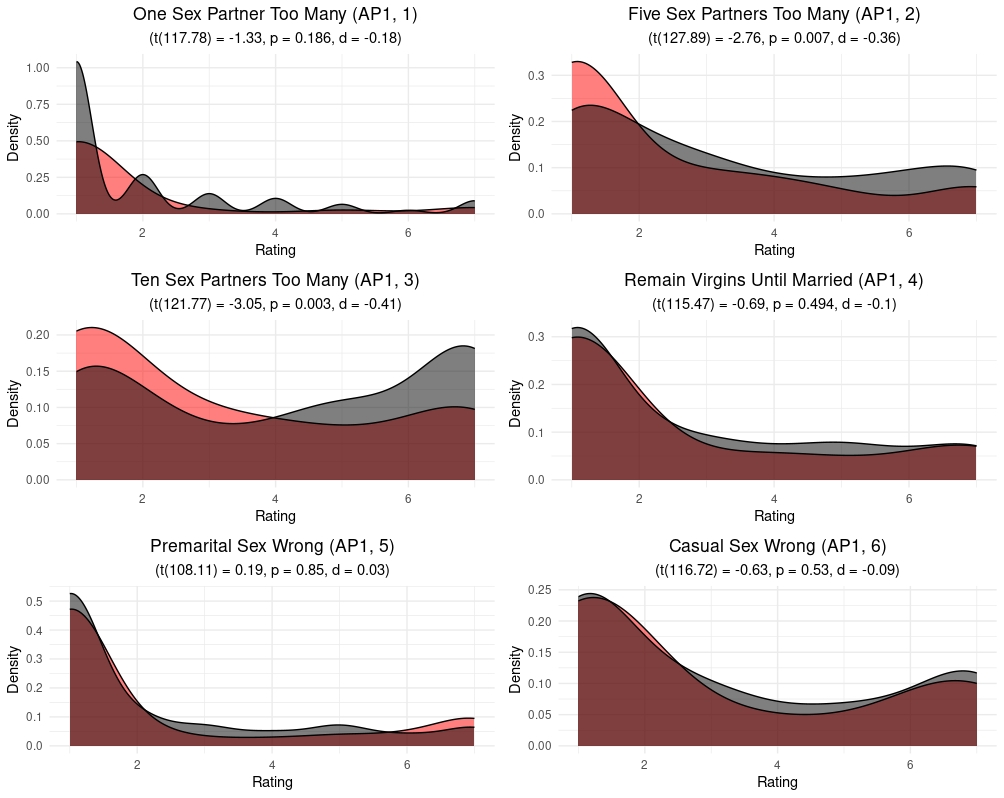

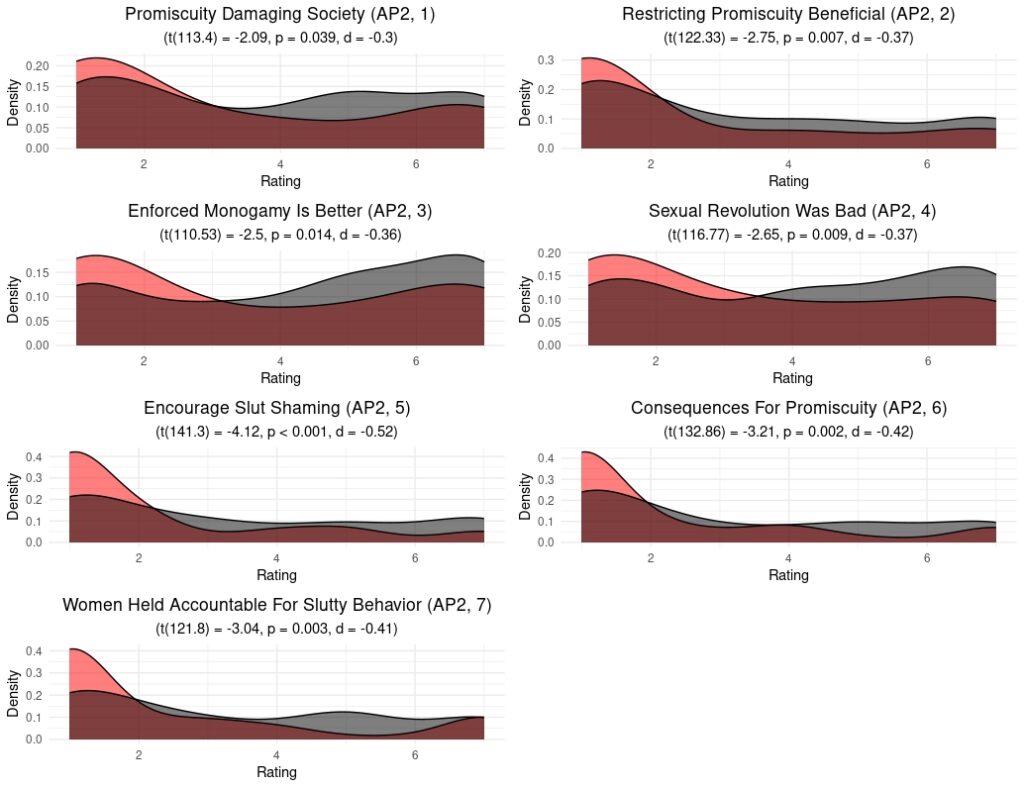

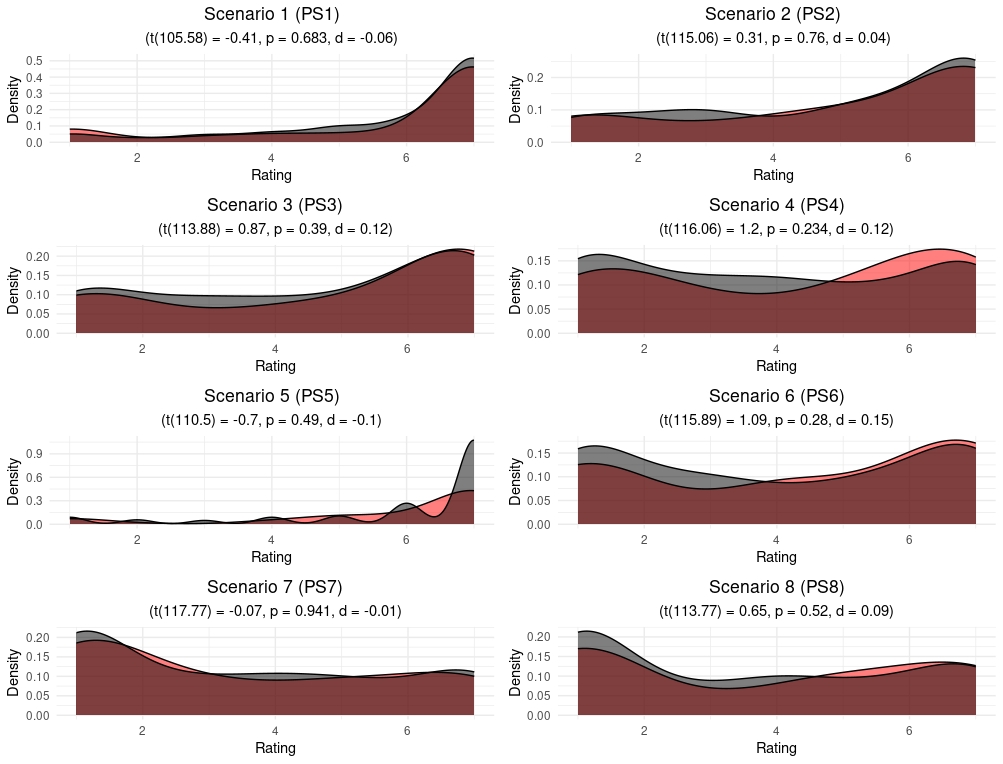

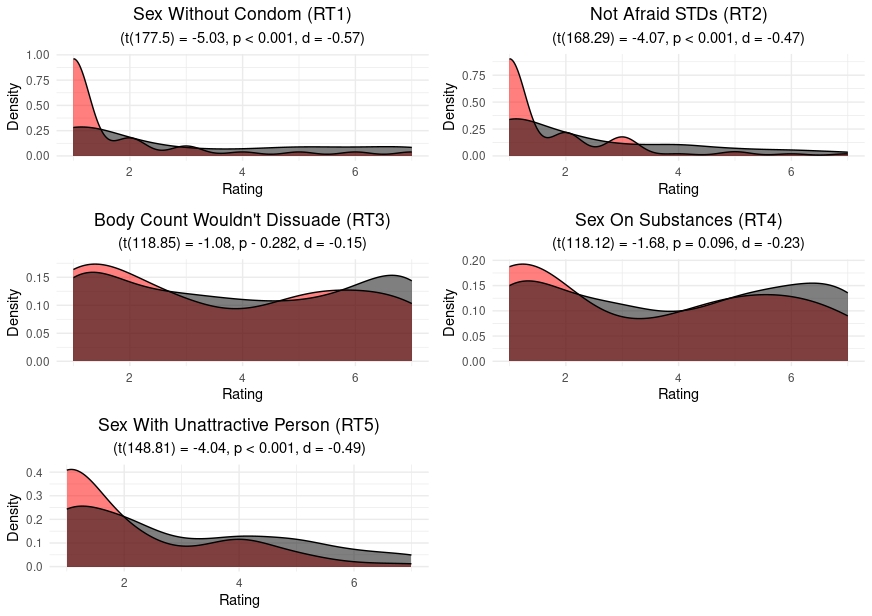

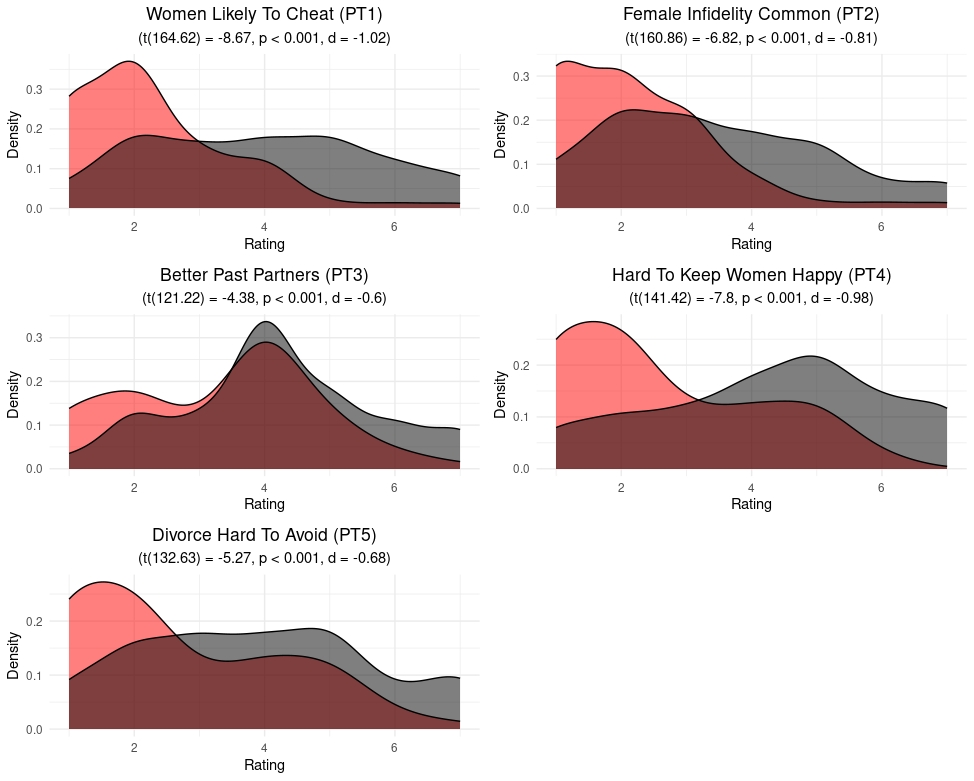

This section contains scales used in the study. At the bottom of this article is an appendix with participant responses for each scale item split by sex with t-test results and Cohen’s d effect sizes (black / gray = Male, red / pink = Female).

Frustrated Mating Scale (FMS) (α = .80) to assess self-perceptions of difficulty with romantic and sexual success with the following items:

- If I am attracted to someone, they often are not attracted to me in return.

- I don’t feel like I have had as much sexual or romantic experience as I would have liked for my age.

- Finding a quality person who I would like to date is hard.

- I have not done very well on dating apps, or I don’t feel like I would do very well on dating apps if I used them.

- I have spent longer periods of time single than I would have liked.

- I tend to find navigating the dating scene to be frustrating.

- I have experienced a lot of romantic rejection in my life.

- When I was a teenager, I had little in the way of teenage love.

Individual Attitudes Toward Female Promiscuity (AP1) (α = .95) assesses personal attitudes toward female promiscuity:

- For women, one past sexual partner is too many.

- For women, five past sexual partners is too many.

- For women, ten past sexual partners is too many.

- Women should remain virgins until they are married.

- It is wrong for a woman to have premarital sex, or sex before marriage.

- It is wrong for a woman to have casual sex.

Social Attitudes Toward Female Promiscuity (AP2) (α = .95) assesses perceived social consequences and support for limitations on female promiscuity:

- Female promiscuity is very damaging for society.

- Society would be better if we restricted female promiscuity in some way.

- It is better to have “socially enforced monogamy.”

- The Sexual Revolution was mostly bad for Western culture.

- “Slut shaming” should be encouraged to control female promiscuity.

- Women who are promiscuous should face consequences for it.

- Women need to be held accountable for slutty behavior.

Promiscuity Scenarios (PS) (α = .95) describe real-world scenarios of sexual behavior:

- A woman is 20 years old and has been dating her same-age boyfriend for a month. They are both virgins and they have sex for the first time.

- A woman goes onto Tinder and meets a man that she finds very attractive. They go on two dates and she has sex with him on the second date.

- A woman is in her second year in university and begins a friends-with-benefits relationship with a male classmate she finds attractive. They never form a committed relationship, but they meet up a couple of times each week for sex.

- A woman in college goes to a frat party and has sex with the captain of the football team in the bathroom.

- A 35-year-old woman has dated four men in her life and she had sex with each of them. She has never had sex with anyone aside from those four men.

- A woman uses dating apps exclusively for casual sex. She finds men that she is attracted to and has sex with them often.

- A woman signs up for OnlyFans and occasionally has sex with her subscribers for cash.

- A woman is active in a fetish community and often organizes orgies where she has sex with multiple men at the same time.

Sexual Risk-Taking (RT) (α = .74) assesses participant willingness to engage in sexual risk behavior:

- I would have casual sex with an attractive stranger without using a condom.

- I would not be very afraid of catching a sexually transmitted disease from a hook-up partner.

- Knowing that someone has had many past sexual partners would not make me less likely to have sex with them.

- I would have sex with someone under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

- I would have sex with someone who I am not very attracted to.

Perceived Threat of Romantic Loss (PT) (α = .84) assesses perceptions of the risk of romantic defection:

- Women are likely to cheat on a man if they find someone better.

- Female infidelity is very common; women cheat often on their male partners.

- Most women have had past sexual or romantic partners who are better than their current partner.

- It is hard to keep a woman happy over the long run.

- Divorce is hard to avoid or prevent.

Results

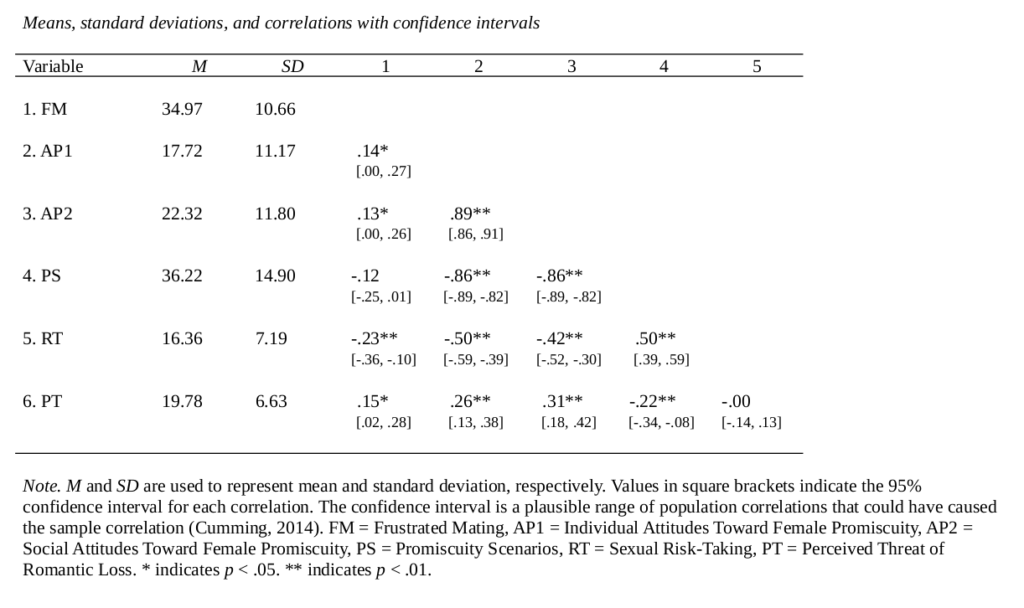

Table 1 above shows correlations for total scale scores. Frustrated mating was significantly associated with individual attitudes toward promiscuity (r = .14), social attitudes toward promiscuity (r = .13), sexual risk-taking (r = -.23), and perceived threat of romantic loss (r = .15). Participants who perceived themselves as having less success in the romantic and sexual marketplace had more restrictive personal views on female promiscuity, believed female promiscuity was more harmful for society (and supported more limitations on female sexuality), were lower in personal willingness to engage in sexual risk behaviors, and had a higher perception of the risk of romantic loss.

Willingness to take sexual risks was significantly associated with all study variables except for perceived risk of loss. Participants higher in sexual risk-taking had less restrictive personal (r = -.50) and social (r = -.42) attitudes toward promiscuity, approved of promiscuity scenarios more (r = .50), and experienced lower frustrated mating (r = -.23).

Perceived threat of loss was significantly associated with frustrated mating (r = .15), individual (r = .26) and social (r = .31) attitudes toward promiscuity, and sexual risk-taking (r = -.22). Participants who believed women were more likely to defect from relationships or be unfaithful experienced more frustrated mating, had more restrictive individual and social attitudes toward promiscuity, and were less willing to engage in sexual risk-taking behaviors themselves.

Discussion

Frustrated Mating

Consistent with past research, the current study found a significant relationship with frustrated mating and attitudes toward promiscuity. Men who feel as if they have been less romantically and sexually successful have more sexually restricted attitudes and are more willing to support social restrictions on female sexuality.

Sexual Risk-Taking

Sexual risk-taking emerged as a strong predictor of attitudes toward female promiscuity. Men who expressed a higher willingness to take sexual risks experienced lower frustrated mating and had less restrictive attitudes toward female promiscuity. Further, in our exploratory analysis men higher in sexual risk-taking were more likely to be in committed relationships or married.

Perceived Loss or Defection

Men who judged women as having a higher risk of infidelity, divorce, and extra-pair interest had more restrictive views on female sexual promiscuity and were more supportive of social restrictions on female sexual behavior. In this case, restrictive attitudes toward promiscuity may represent a threat-reduction strategy. Men who believe women are more likely to defect from relationships may adopt beliefs in support of restricting female sexuality in order to reduce their own fears of infidelity or cuckoldry.

This is consistent with the observed relationship between frustrated mating, or low romantic success, and restrictive attitudes. For example, if sexually successful men who easily fulfilled short-term mating goals perceived women at high risk of defection, we would not expect this to produce the same associations, as restrictions on their chosen mating strategies would not facilitate them. To use an analogy, we would expect the sheep to support the sheepdog and shepherd more than we would expect the wolves to support the sheepdog and shepherd.

Additionally, perceived loss was associated with frustrated mating. This may reflect negative or more extreme perceptions developed from frustrated mating itself, or alternatively mating-related fears may lead to more withdrawal and subsequent lower mating success and more mating frustration. Men who perceive women as unlikely to remain faithful to them may sabotage their own romantic trajectories.

Sex Differences on Scale Items

Interestingly, men did not judge real-world scenarios of sexual promiscuity more harshly than women. Where men did differ from women, however, was in support for restrictions on female sexuality and perceptions of female promiscuity as harmful.

Conclusion

The current research demonstrates relationships between frustrated mating, attitudes toward promiscuity, and relational as well as sexual risk perceptions. Negative attitudes toward promiscuity may be understood as risk reduction strategies that facilitate the mating goals of men who are more risk-avoidant and less successful in the sexual or romantic marketplace.

Appendix / Scale Descriptives

Scales and Sex Differences

Make sure to see the original items in the Methods section above; the titles of these plots are not exactly the same as the question (due to space on the charts).

References

Arnocky, S., Ribout, A., Mirza, R. S., & Knack, J. M. (2014). Perceived mate availability influences intrasexual competition, jealousy and mate-guarding behavior. Journal of Evolutionary Psychology, 12(1), 45-64.

Bosson, J. K., Rousis, G. J., & Felig, R. N. (2022). Curvilinear sexism and its links to men’s perceived mate value. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(4), 516-533.

Costello, W., & Buss, D. M. (2023). Why isn’t there more incel violence?. Adaptive human behavior and physiology, 9(3), 252-259.

DeScioli, P. (2023). On the origin of laws by natural selection. Evolution and Human Behavior.

Gouda-Vossos, A., Brooks, R., & Dixson, B. (2023). Experimentally Varying Sex Ratios and Masculine Cues Affect Attitudes Towards Promiscuity and Self-Reported Mate Value.

Grunau, K., Bieselt, H. E., Gul, P., & Kupfer, T. R. (2022). Unwanted celibacy is associated with misogynistic attitudes even after controlling for personality. Personality and individual differences, 199, 111860.

Hamilton, A. (2022). Characteristics of those who identify as ‘incels’.

Lankford, A. (2021). A sexual frustration theory of aggression, violence, and crime. Journal of criminal justice, 77, 101865.

Luberti, F. R., Blake, K. R., & Brooks, R. C. (2022). Changes in Positive Affect Due to Popularity in an Experimental Dating Context Influence Some of Men’s, but Not Women’s, Socio-Political Attitudes. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 8(2), 202-237.

Sevi, B., & Shook, N. J. (2021). The relation between disgust sensitivity and risk-taking propensity: A domain specific approach. Judgment and Decision Making, 16(4), 950-968.

Surbey, M. K., & Brice, G. R. (2007). Enhancement of self-perceived mate value precedes a shift in men’s preferred mating strategy. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 39(3), 513-522.

Teng, F., Wang, X., Li, Y. A., Zhang, Y., & Lei, Q. (2023). Personal Relative Deprivation Increases Men’s (but Not Women’s) Hostile Sexism: The Mediating Role of Sense of Control. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 47(2), 231-249.

Zhang, J., Mollandsøy, A. B., Nornes, C., Erevik, E. K., & Pallesen, S. (2024). Predicting hostility towards women: incel‐related factors in a general sample of men. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology.

7 comments

This study you conducted has a flaw that should be corrected. The mate value scales in many studies are subjective self perception scales and that’s true for your frustrating mating needs scale. This is why studies mistakenly say that unwanted celibacy is associated with misogyny. These scales are based on self perception.

Your “are chads misogynistic?” Article uses the same flaw in the study and the extreme misogyny scale has statements that aren’t misogynistic, which can inflate how high virgin men could score in it. Some studies you cited also use fictitious rejection experiments which doesn’t show how men who actually get rejected constantly think like.

Here’s a post debunking that there’s a link between virginity and misogyny. Misogynistic men are promiscuous men who just think they struggle getting sex.

https://www.reddit.com/r/LeftWingMaleAdvocates/s/SS012r074Q

One more blackpill to add to the pile.

Alex, I really don’t understand why you’re so against the blackpill even when YOUR OWN RESEARCH proves us right.

I do think he can be good with research but he does have his flaws

The issue is not with his research per se, but how he interpretates it and fit it into his elitist and anti-incel worldview. To me the reality of good-gene sexual selection means society must help those who were born with shit genes to enjoy sex and love. But to him because hes an elitist he has the opposite interpretation.

In other words it’s about fact-value distinction. His research is good, his values suck, and he doesn’t seem to be aware how to decouple them.

The usual misogynist is just some promiscuous, dark tetrad man who thinks he struggles with getting sex or relationships when he doesn’t because he believes he must have as many sex partners as possible and a zero percent rejection rate.

It’s like a man with muscle dysmorphia who thinks he has no muscle when he’s extremely muscular and is a roidhead.

I don’t disagree with that but it’s not the whole picture. Misoginy is curvilinear: chads despise women, we hate them. As I said, his research is mostly sound.

We must face the truth: we unattractive men (I assume you are too) can’t get laid in a normal society because women (and chads) despise us. We are like the sole guy on the other track in the trolley problem: our interests are opposed to that of the majority. Alex is like the guy choosing to switch and kill us to save the greatest number.

My point is: by fighting back, we will necessarily be on the bad side. But we must anyway, because a life without sex and love is not a life worth living. Obviously I can’t be more explicit without getting banned.

Sexual frustration might be linked to not Wanting to have casual sex, so Wanting a committed Relationship. Sexual frustrated men might be shy, sensible, highly conscientious and self-critical, risk-averse.

Men wanting casual sex might think less than others, don’t care about long term plan, are more arrogant… and so develop extraversion, confidence, social skills.

So it’s not about attractive, satisfied men vs unattractive, frustrated men.

It’s more like casual, impulsive men vs serious, thoughtful men.