An Introduction to Partner Counts, Self-Reporting, and Status-Seeking

Past research has consistently found that men report more sexual partners, on average, than women do (for a review, see Is Self Reported Sexual Partner Data Accurate?). A great deal of popular discourse on this topic proposes that this is an effect of social desirability bias, or more specifically stigma impacting participant willingness to report honestly.

However, social desirability bias is not merely an avoidance of stigma. People don’t just avoid reporting what would make them look bad, but also exaggerate self-reports in such a way that makes them look good.

It is rare that anyone faces consequences, social or otherwise, for what they report as a research participant. Most survey-based research is anonymous, not only to third parties but also to the researchers conducting the survey or experiment. There is little plausible reason why anyone would expect consequences to arise from honest reporting. Indeed, the introduction of anonymous survey practices also induces people to report about as honestly as they would if they were hooked up to a polygraph machine and told they would be caught.

In other words, participants aren’t necessarily motivated to lie to others as much as they are motivated to lie to themselves. Dishonest or inaccurate reporting fulfills an emotional need for congruence with one’s own self image. Much research has focused on the supposed need for women to present a chaste image to others. Less research has examined what men gain from overreporting sexual partners.

Jonason, 2007

Evolutionary psychologist Peter Jonason (2007) proposed that men may exaggerate self-reports of sexual success for prestige and status. In the first study, men reported having more sexual success than women. Men also associated status more closely with promiscuity. In other words, having more sexual partners was more of a status symbol to men than to women. When status was accounted for, the sex difference in self-reported sexual success disappeared.

Basically, men who saw sexual conquests as status-enhancing were inflating their own partner counts.

In the second study, men rated vignettes describing other men who had 50 sexual partners as more prestigious than they rated vignettes describing men with 5 sexual partners. Further, men also rated female vignettes with more sexual partners as slightly more prestigious than female vignettes with fewer sexual partners. Perhaps contrary to popular perception, promiscuity was not a penalty to prestige for the female vignette target. To men, sex was associated with status, even when assessing women.

Jonason & Fisher, 2009

Jonason and Fisher (2009) replicated and extended the previous findings of Jonason (2007). In this research, male participants reported that sexual partner quantity and quality was more important than female participants did. Male participants also reported a higher number of past sexual partners than female participants did. Further, male and female participants reported higher prestige for more promiscuous men and, once again, for most promiscuous women.

As in Jonason’s original research, the sex difference in self-reported past partner count was fully moderated by perceptions of promiscuity enhancing prestige. It turned out that men who believed promiscuity was more prestigious were also reporting that they had more sexual partners. When this was accounted for there was no sex difference in sexual reports between men and women.

In our current research, we sought to extend associations similar to those in Jonason (2007) and Jonason and Fisher (2009).

Methods

We collected a snowball sample of 338 participants from social media. Participants reported their lifetime number of past sexual partners, indicated if they knew their exact number of past sexual partners (binary YES/NO), sexual orientation, and age.

Participants also responded to a seven item scale describing male promiscuity and male sexual success, as well as the same scale with the sex of the target changed to female. A single item was used to measure if having a high number of sexual partners was stigmatizing for men. this was later reworded to ask if a high number of sexual partners was stigmatizing for women. Participants were also asked to indicate what they believed an ideal number of sexual partners was for men and women, as well as how many sexual partners was “too many” for men and women.

A six item scale was used to assess how necessary quality was in a sexual partner and a seven item scale was used to assess how much participants desired sexual quantity, or sexual variety with multiple partners.

All items used a 7-point linear response scale. Seven participants who indicated same-sex orientation were removed for the analysis, as we instructed participants to report only penile-vaginal intercourse. Sixteen participants were removed for not indicating numbers for ideal or “too many” sexual partner items. The final sample was 315 participants.

Data, code, and full survey questions are available here.

Results

Quality and Quantity of Sexual Partners, Perceptions of Status, and Promiscuity

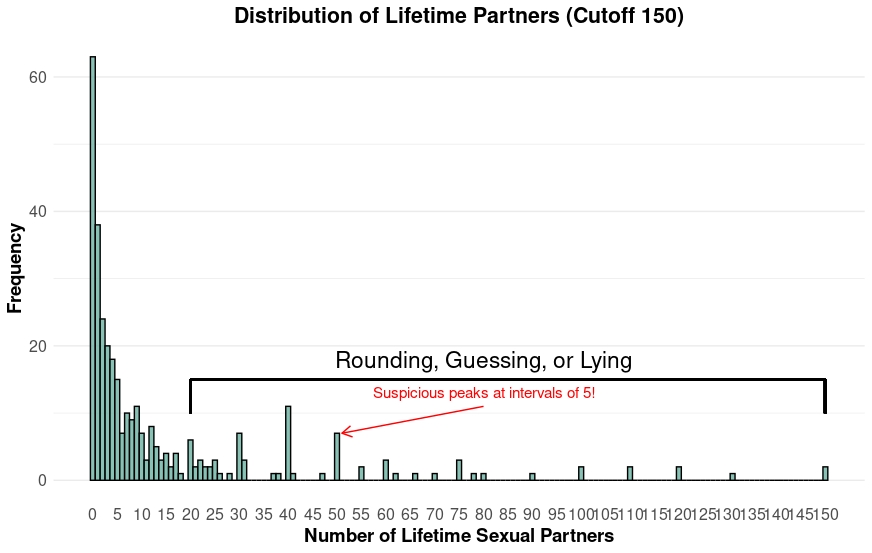

Table 1 shows a correlation table of all variables in our current study. Summarizing findings pertinent to past research in Jonason (2007) and Jonason and Fisher (2009):

- Desire for sexual quantity (or desire for sexual variety) was negatively correlated with a need for quality in a sexual partner (r = -.43).

- Self-reported lifetime partner count was positively correlated with a desire for sexual quantity (r = .44) and negatively correlated with a need for quality (r = -.22).

- Self-reported partner count was positively correlated with perceptions of promiscuity as status-enhancing both when assessing male targets (r = .15) and female targets (r = .12).

- Self-reported partner count was positively correlated with a higher ideal number of sexual partners when assessing male targets (r = .50) and female targets (r = .44).

Perceptions of Status and Ideal Partner Count by Sexual Reporting Strategy

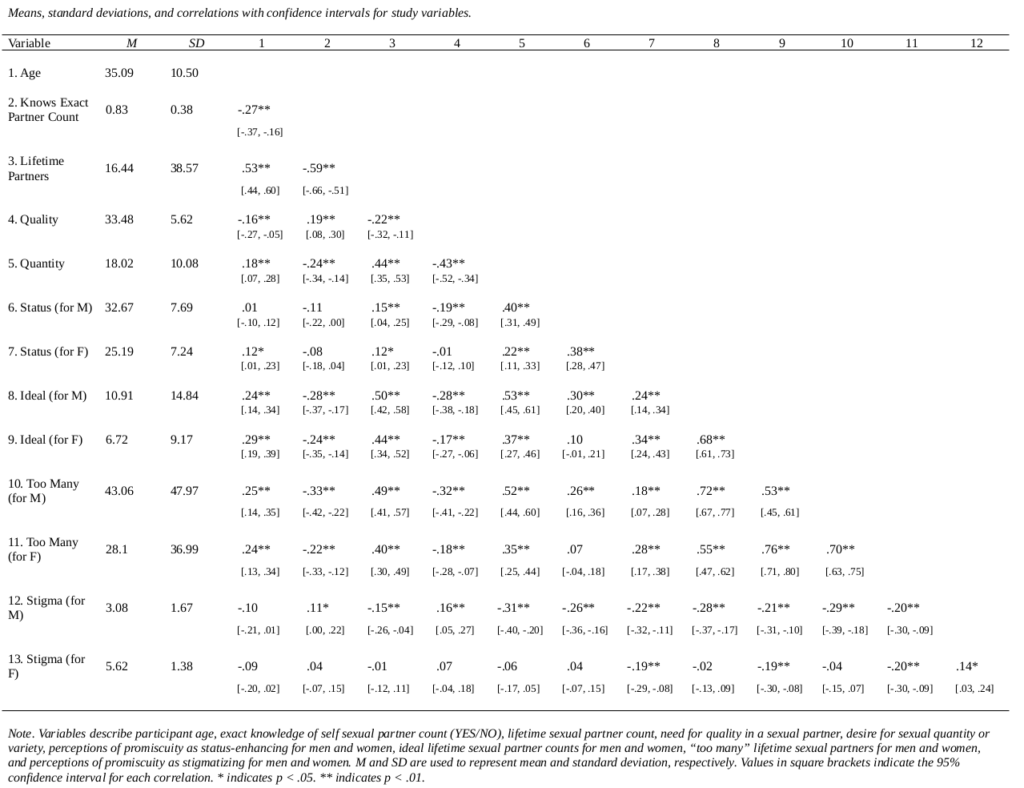

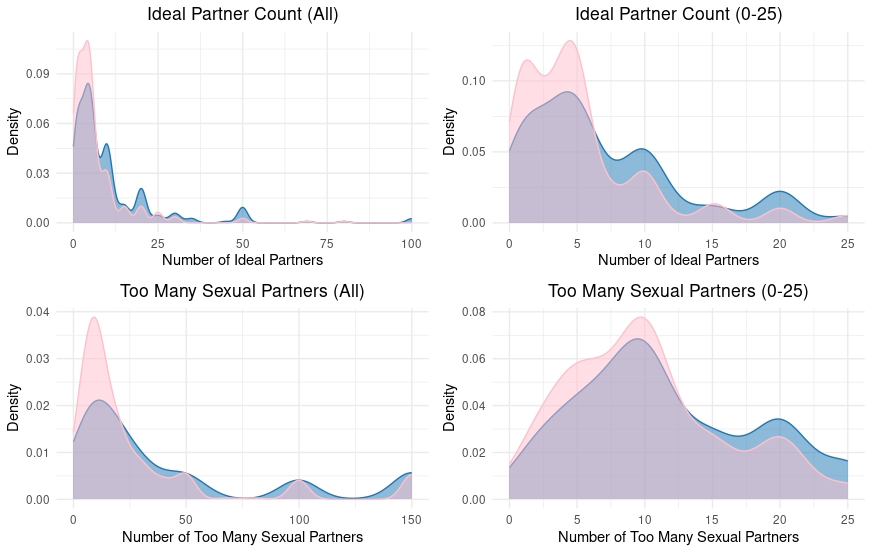

Consistently across past research on self-reported sexual partner count, a pattern of reporting emerges where participants disproportionately report large numbers in multiples of five. This pattern of reporting may be attributed to losing count, rounding, guessing, exaggerating, or lying. Past research has also found that men tend to do this more — and that when rounding strategies are accounted for the discrepancy in self-reported sexual partner count disappears (Morris, 1993; Wiederman, 1997). In our data we also find this reporting pattern (Image 1).

If higher self-reported partner counts are driven by a desire to signal status or other social desirability (e.g. “higher partner counts are better”), we may expect higher perceptions of status and higher ideal partner counts to be associated with higher self-reported actual partner counts and the use of a rounding strategy when reporting.

Differences in Perceptions of Promiscuity as Status-Enhancing

Participants who reported having over 50 lifetime sexual partners were significantly more likely to say that higher levels of promiscuity are status-enhancing for male targets (t(34.94) = 2.72, p = 0.01, 95% CI [0.95, 6.55], d = 0.49), but were not more likely to believe that higher levels of promiscuity are status-enhancing for female targets (t(32.51) = 1.00, p = 0.32, 95% CI [-1.62, 4.75], d = 0.21).

There was no significant difference in perceptions of promiscuity as status-enhancing for male targets by participants who used a rounding strategy compared with participants who gave exact numbers of past lifetime partners (t(74.14) = 0.97, p = 0.34, 95% CI [-1.17, 3.38]). Similarly, no significant difference was found for perceptions of promiscuity as status-enhancing for female targets between these two groups (t(68.44) = 1.14, p = 0.26, 95% CI [-1.01, 3.68]).

Differences of Belief in What An Ideal Partner Count Is

Participants who reported having over 50 lifetime sexual partners were significantly more likely to report that men should have a higher ideal number of sexual partners (t(30.30) = 3.39, p = 0.002, 95% CI [5.36, 21.64], d = 0.95), but not that women should have a higher ideal number of sexual partners (t(31.43) = 1.52, p = 0.14, 95% CI [-1.14, 7.75], d = 0.36).

Participants who used a rounding strategy when self-reporting their own lifetime partner count were significantly more likely to report a higher number of sexual partners as ideal for men (t(64.00) = 4.21, p < 0.001, 95% CI [5.65, 15.84], d = 0.75) and for women (t(55.77) = 3.63, p < 0.001, 95% CI [3.38, 11.70], d = 0.86).

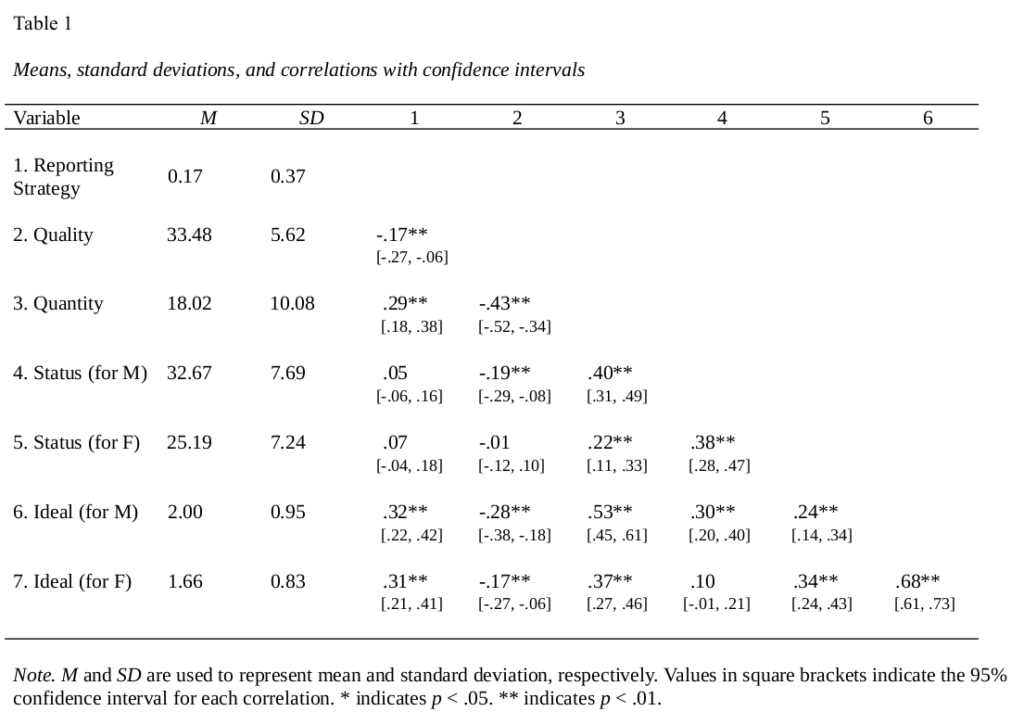

Table 2 shows correlations between self-reporting strategy and selected variables.

A significant association between the use of a rounding reporting strategy and perceptions of promiscuity as status-enhancing was not found for men (r = .05) nor women (r = .07) (Table 2). The use of a rounding reporting strategy was associated with reporting a higher number of ideal sexual partners (for men, r = .32; for women, r = .31).

Sexual Double Standards (SDS)

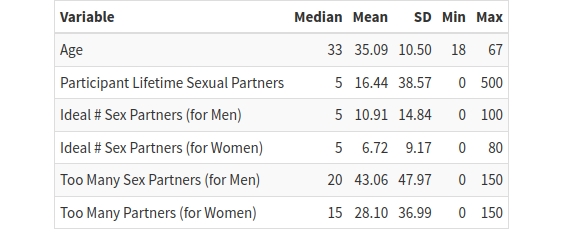

Promiscuity was perceived by participants as being more status-enhancing for male targets than for female targets (t(625.72) = 12.57, p < 0.001, 95% CI [6.31, 8.65], d = 1.00). Participants also reported a higher ideal partner count for men than for women (t(523.31) = 4.26, p < 0.001, 95% CI [2.26, 6.12], d = 0.34). Additionally, participants reported a higher number of sexual partners as “too many” for men than for women (t(589.92) = 4.38, p < 0.001, 95% CI [8.26, 21.66], d = 0.35). Higher numbers of sexual partners were also perceived as less stigmatizing for men than for women (t(607.06) = -20.77, p < 0.001, 95% CI [-2.78, -2.30], d = -1.65).

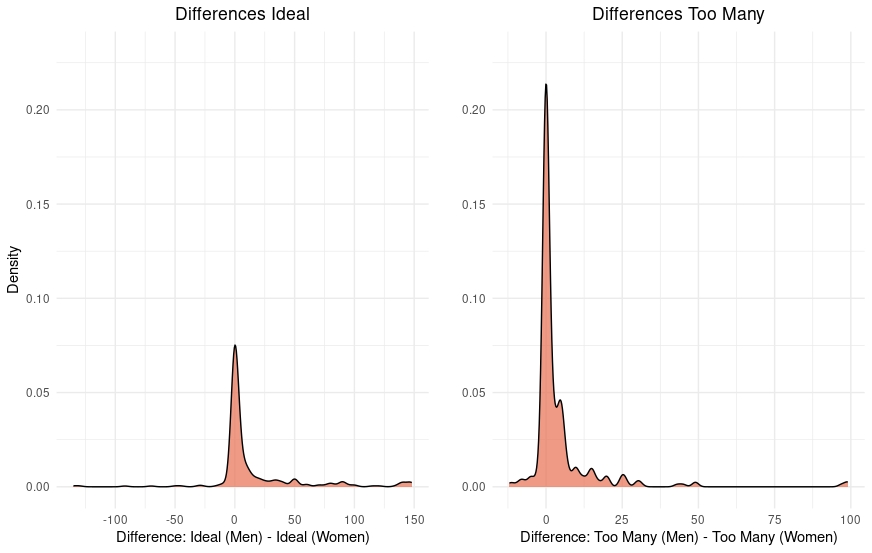

Table 3 shows descriptive statistics for variables measuring sexual double standards while Image 2 shows density plots of differences in what participants report as ideal and “too many” sexual partners.

Image 3 shows density plots for the differences in ideal and “too many” partners for male and female targets. In addition to the density plots in Image 2, this is another way to visualize the magnitude of the sexual double standard.

For most participants, an ideal number of sexual partners, as well as “too many” sexual partners, for men and women is fairly similar. 83.17% of participants reported ideal sexual partner counts for men and women to be within five partners of each other while 67.19% of participants reported that “too many” sexual partners for men and women were within five partners of each other.

Many Participants Sexual History Differs From Their Own Stated Ideals

A substantial minority of participants reported having more sexual partners than what they perceived as ideal in male or female targets. 36% of participants reported having more lifetime sexual partners than what was ideal for men and 46% reported having more lifetime partners than what was ideal for women. 9% reported having more lifetime partners than what was “too many” for men and 18% more than what was “too many” for women.

If social desirability bias exists, it is not strong enough to fully prevent individuals from admitting that they have exceeded their own ideals.

Differences Between Virgins and Nonvirgins

19.67% of the sample reported that they had zero past sexual partners. There was no significant difference in the perceived stigma of male promiscuity between virgins and nonvirgins (t(85.61) = 1.03, p = 0.304, 95% CI [-0.24, 0.76], d = 0.15), nor was there a difference in the perceived stigma of female promiscuity between these two groups (t(90.93) = -0.24, p = 0.814, 95% CI [-0.43, 0.34], d = -0.03).

Virgins did not report a significant difference in an ideal number of sexual partners for men (t(71.92) = -1.27, p = 0.208, 95% CI [-8.78, 1.95], d = -0.23), but did report a lower ideal number of sexual partners for women (t(88.10) = -2.39, p = 0.019, 95% CI [-5.67, -0.52], d = -0.35).

There was a significant difference in the perception of “too many” sexual partners for men between virgins and nonvirgins, (t(116.99) = -4.27, p < 0.001, 95% CI [-35.49, -13.01], d = -0.52). There was also a significant difference in the perception of having “too many” sexual partners for women between virgins and nonvirgins, (t(123.38) = -3.50, p < 0.001, 95% CI [-23.16, -6.42], d = -0.41).

Virgins did not show significantly higher sexual double standards than nonvirgins for ideal partner counts (t(67.241) = −0.13 p = 0.896, 95% CI [−5.18,4.54]) nor “too many” partner counts (t(90.58) = −1.76, p = 0.083 95% CI [−20.17,1.24]).

Discussion

Biases in Self-Reporting Sexual Partner Count Driven By Status and Ideals

Overall, our results were consistent with Jonason and Fisher (2009). An exception was that we found negative correlations between a need for partner quality across our variables, while Jonason and Fisher found positive correlations. This could simply be due to differences in the scales used.

However, finding that participants who cared more about sexual quantity, or who desired more sexual partners, also cared less about partner quantity is not necessarily a surprising result. Trade-offs between partner quality and quantity may facilitate a strategy for individuals who desire more sexual variety or novelty to reach their goals (Hirsch & Paul, 1996). Individuals who are more promiscuous have also been found to have lower standards, or to make more downward selections (Jonason et al., 2011), as well as to have lower sexual disgust (Burtăverde et al., 2021).

Consistent with Jonason and Fisher (2009), participants who perceived higher sexual partner counts as status-enhancing also reported having more lifetime sexual partners themselves. Also consistent with Jonason and Fisher, this was true when assessing both male and female targets. Participants who reported more lifetime sexual partners for themselves also reported a higher ideal number for both male and female targets, as well as a higher number of partners as “too many” for male and female targets.

We found the use of a rounding reporting strategy in our data, similar to most samples of sexual partner count (Morris, 1993; Wiederman, 1997). Participants who reported large numbers of sexual partners (50 and above) were more likely to endorse promiscuity as status-enhancing for men, but not for women. Use of a rounding strategy in reporting, however, did not predict differences in how promiscuity was assessed as status-enhancing.

Ideal partner counts were higher for participants who had a high number of sexual partners themselves (50 or over), but only when assessing male targets. Participants who used a rounding strategy reported higher ideal partner counts both for male and female targets.

Overall, these results provide partial support for the hypothesis that self-reporting more sexual partners is associated with perceptions that having more sexual partners is status enhancing (in particular, for male targets) and that higher numbers of sexual partners are ideal.

Sexual Double Standards

Evidence for sexual double standards indicated that promiscuity was perceived as more stigmatizing to women than to men, an ideal number of sexual partners was lower for women than for men, and “too many” sexual partners was lower for women than for men.

However, perceptions of ideal and “too many” sexual partners were closely associated for male and female targets (r = .70). Very large sexual double standards were uncommon. Most participants reported an ideal number of sexual partners for male and female targets to be within five of one another.

In line with our own past research (see: Who Are The Men That Demand Virgins?), participants who had zero past sexual partners believed that an ideal number of sexual partners and “too many” sexual partners were lower for female targets than participants who had been sexually active in the past.

Finally, relatively few participants reported that zero to one sexual partners was ideal for men (20%) or for women (27%). The median ideal number of sexual partners for both male and female targets was 5.

Conclusion

Perceptions of sexual success as a status-enhancing ideal are associated with self-reports of one’s own sexual partner count. Individuals who perceive having more sexual partners as ideal are more likely to use unreliable reporting strategies when communicating their own sexual behavior.

References

Burtăverde, V., Jonason, P. K., Ene, C., & Istrate, M. (2021). On being “dark” and promiscuous: The Dark Triad traits, mate value, disgust, and sociosexuality. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110255.

Hirsch, L. R., & Paul, L. (1996). Human male mating strategies: I. Courtship tactics of the “quality” and “quantity” alternatives. Ethology and Sociobiology, 17(1), 55-70.

Jonason, P. K., Valentine, K. A., Li, N. P., & Harbeson, C. L. (2011). Mate-selection and the Dark Triad: Facilitating a short-term mating strategy and creating a volatile environment. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(6), 759-763.

Morris, M. (1993). Telling tails explain the discrepancy in sexual partner reports. Nature, 365(6445), 437-440.

Wiederman, M. W. (1997). The truth must be in here somewhere: Examining the gender discrepancy in self‐reported lifetime number of sex partners. Journal of Sex Research, 34(4), 375-386.