Man The Hunter, or Not?

Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

Popular science has been abuzz with recent attempted debunkings of “Man The Hunter.” Broadly, “Man The Hunter” is the observation that across hunter-gatherer societies men tend to be the primary, sometimes sole, hunters. A recent paper by Anderson et al. (2023) captured headlines by claiming that women hunted, too — and it gave wildly large estimates for female hunting behavior. Scientific American recently published an editorial claiming that women hunted as often as men, based largely on circumstantial evidence indicating that it is possible for women to hunt. For example, arguing that the cardiovascular capacity of women makes them suitable for long distance persistence hunting.

When I combed through the original data used in the Anderson et al. (2023) paper, I immediately found errors in the coding. Women do hunt, not infrequently, but not nearly as often as Anderson et al. estimated (based on the same sources they used to produce their figures). Additionally, when women hunt it is rarely large game and often consists of group hunts with nets. In other words, women trap small game. Independent of me, anthropologist Vivek Venkatarman issued a criticism of the Anderson et al. methodology. A more recent paper by Hoffman et al. (2023) similarly found a much lower rate of female hunting, also noting that when women do hunt it is in a fundamentally different fashion from that of men. Female hunting is rarely the pursuit of large game.

The anthropological data indicating that men hunt more across cultures is robust. In some cultures women hunt frequently, but in some cultures women do not hunt at all. I am not aware that any culture exists where women exclusively hunt while men do not hunt. Additionally, it’s important to note that no one has ever claimed women never hunt in hunter-gatherer societies. The observations of “Man The Hunter” show a consistent average trend: men hunt more. No one has ever claimed that a woman has never killed a rabbit.

What, then, is the real motive for pushing a “women hunt, too” narrative when no one has disputed this? The “blank slate” is still alive for some, particularly in anthropology with its large focus on culture, even if we know from the fields of behavioral genetics and personality psychology that behavior is heritable. The zeitgeist of gender egalitarianism may also drive some to deny that sex differences are real, or that sex differences are entirely cultural: “See? In this culture women hunt just as much! Ignore the two-standard-deviation difference in upper body strength and average cross-cultural trends where men hunt more.”

We also tend to devalue foraging and gathering relative to hunting. Hunting is cool, picking berries is not. The man is depicted as killing the mammoth while the woman is portrayed sitting in the cave. Further, the man can do something that the woman cannot; or he can do it better. We don’t dispute that men can forage, but we do dispute that women are equally effective hunters.

Hunting is seen as particularly important. This, by the way, is a perception that is not entirely accurate. In many hunter-gatherer societies, foraging produces more calories and a more steady source of calories. Gathering is crucial, it’s not really a lesser task, but nonetheless we want to believe we would have killed the mammoth and the elephant. We don’t want to believe we would have been digging roots all day long.

Why Don’t Women Hunt More Today?

Despite the hype over pieces like the Anderson et al. (2023) paper or the SciAm article, it’s notable that in the modern Western environment women also hunt less than men do. “Women are hunters, too” — really, are you though? How many animals have you killed? Women who have never hunted in their lives, who probably would not enjoy killing an animal, nonetheless related in some way to the narrative that they, too, would have been great hunters in the Pleistocene.

When I made the posts below on Twitter (now called X) it got picked up by Spanish language Twitter. I saw hundreds of comments that boiled down to, “My abuela killed rabbits all of the time,” and pictures of paella with rabbit meat. What’s notable is that almost no one said, “Yes, I have done this. I hunt rabbits.” At best, they could claim that a woman two generations distant from them did it. At the same time, an equal number of people were astounded to learn that young boys frequently kill neighborhood animals for recreational fun.

This rule of thumb will help you understand (at least some) human behavior: people do what they want to do. We also tend to do what we are good at. This also means people avoid things they don’t want to do and things that they are bad at. We live in an environment where few people need to butcher rabbits, unlike the Hadza of Tanzania or your abuela in 1920s Spain. If people hunt in the West it’s because they have gone out of their way to do so. They hunt because they want to hunt.

This raises some questions. Why do men hunt more? Do men want to hunt more than women? If men do want to hunt more, why? Hypotheses that posit cultural learning and the blank slate might argue that boys, from infancy, are exposed to male gender roles. In Delusions of Gender, Cordelia Fine argues from this position to explain sex differences we see in the brain, as well as personality orientations that develop quite young (for example, male toddlers preferring trucks over dolls). The treatment a baby receives in the crib is, supposedly, sufficient to condition them in favor of all gender roles going forward into adulthood.

Alternatively, a human predisposition or instinct to hunt may be heritable. There is some evidence that children who have never been exposed to any hunting instruction engage in the pursuit and capture of animals regardless. It is well established that aggressive behavior and violent tendencies are heritable. We also see sex differences in physical morphology that would make men more apt for physical violence and hunting with thrown weapons.

Sex differences are found in visuospatial abilities across a range of tasks (Halpern & Collaer, 2005). We also see large sex differences in throwing strength, speed, and accuracy (Lombardo & Deaner, 2018). Why is this so? The hunter-gatherer theory of spatial sex differences proposes that higher visuospatial ability in men was selected for through hunting behavior (Eals & Silverman, 1994). Women have better recall for locations (selected for through foraging or gathering) while men have better visuospatial ability that would have facilitated hunting behavior (throwing a rock or spear).

Underexamined in the evolution of hunting is the role of personality. Men may be better at hunting for physical reasons, but wanting to hunt is also important. Additionally, the emotional reactions that manifest upon killing an animal may shape the evolution of future behavior. If killing an animal is undesirable or unpleasant, even if it were necessary in an ancestral environment, this may have led to self-assortment into a sexual division of labor roles.

Additionally, this may have impacted the efficacy of individual hunters. If hunting is a nerve-wracking experience for you then you may simply be a less effective hunter. This could result in a reduced return of calories. If hunting is exciting or pleasurable then you have more of an incentive to do it. In practice, this could mean an excess of calories or merely meeting the limit. We see this in hunter-gatherers as well: recreational hunting is often common for men. It isn’t common for women.

Hunting may also be understood within the broader context of a willingness to kill. We consistently see sex differences in interpersonal aggression, physical bullying, crime, and pretty much anything violent you can think of. Robustly, men commit acts of violence more than women do. This is very often unnecessary violence — even often recreational or enjoyable violence. Men choose to do this because they want to, just as men choose to hunt in the modern environment because they desire to do so. The environment no longer incentivizes this. Yet, we retain this evolved psychology.

Hunting is not antisocial behavior and I do not intend to draw a full parallel between hunting and antisocial violence. However, in both cases you choose to inflict pain (and death) when you don’t have to. This is not a moral judgment; it is a statement of fact. You have to be comfortable with this to hunt. I hunted as a younger man and later in life raised animals for meat. If I felt terrible when I killed an animal I would not have been able to. If the first time I killed an animal it was a gut-wrenching experience I never would have done it again. That hobby and lifestyle would not have been for me.

Further, if a male predisposition toward hunting were learned solely through social reinforcement we might not expect a sex difference in animal abuse. We do have gendered expectations for hunting. However, we don’t encourage boys to kill cats, nor do we typically encourage them to shoot blue jays in the backyard. We usually have to tell boys not to do that: “Tommy, don’t throw rocks at the bird.”

Boys don’t engage in antisocial aggression toward living creatures because society promotes it; boys do this despite the social messaging against it. Antisocial behavior in general is robust evidence against the blank slate. To this date we have not discovered the optimal environment, the perfect utopia, that builds the perfect human being. Even in the most ideal of conditions we see the dark side of human nature emerge.

Sex Differences in Hunting, Weapons Use, & Aggression

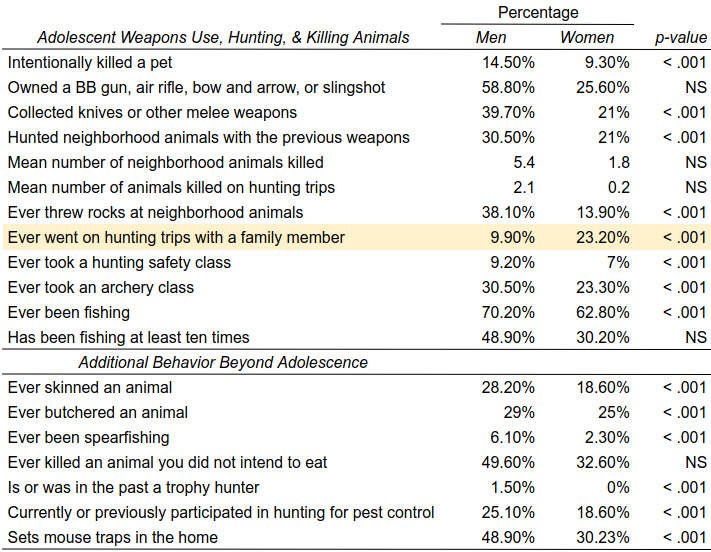

Below are the results from a small survey I ran on adolescent hunting behavior, weapons use, and physical aggression.

We see consistent sex differences across most items. Men were more likely to have intentionally killed a pet, to have hunted neighborhood animals, and to have thrown rocks at neighborhood animals. Even as adults, men were more likely to have set mouse traps in the home.

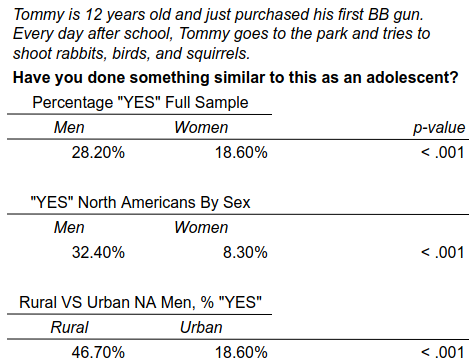

Below is a vignette describing a common adolescent behavior: killing animals in the neighborhood for fun. When I made a post on how boys do this, a lot of people were shocked to learn that this happened at all. Again you can see a sex difference:

Men were substantially more likely to have done this. The percentage of men was higher for North Americans (Europeans may be more concentrated in cities where this is less easy to do). For rural North Americans, it was even higher.

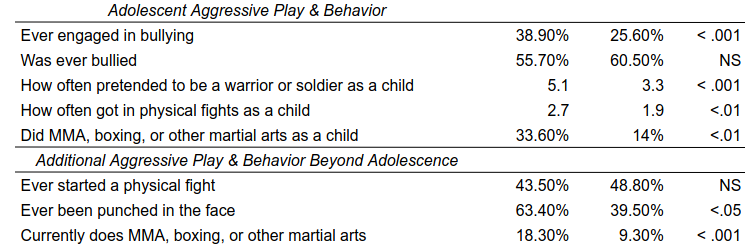

Below are sex differences for men (left column) and women in aggressive play:

Men were more likely to have engaged in bullying, more likely to have pretended to be a warrior or soldier, got in more physical fights as a child, and were more likely to have done martial arts as a child. There was no sex difference in starting physical fights, but men were almost twice as likely to report having been punched in the face.

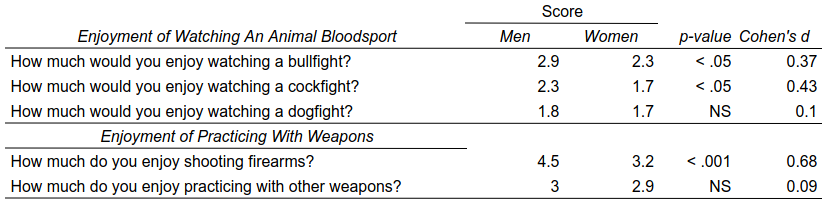

Below are sex differences in the desire to watch animal bloodsports:

Men were more likely to say they would enjoy watching a bullfight or a cockfight, but there was no sex difference in reporting a desire to watch a dogfight.

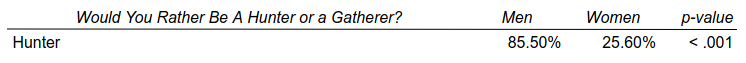

Below are the percentages of men and women who said that, had they lived in past eras, they would have rather been a hunter than a gatherer (Imagine being an early human during the Pleistocene. If you could choose between being a hunter or a gatherer, which of the two would you pick?):

Discussion

We see consistent sex differences in dispositions toward hunting and aggression toward animals. This kind of cross-sectional data can’t show if this is nature or nurture. However, we should consider the possibility that the division of labor by sex in hunting behavior is not merely cultural or environmental. Human beings may have evolved motivations and dispositions of personality, in addition to physical sex differences, that led to the gender roles we see today.

I didn’t cite a lot of research in this article because it is largely absent on this topic. The role of the desire to kill an animal in hunting behavior — and how it may have shaped gender roles — hasn’t been examined at all as far as I could find. Instead, research has tended to focus on who could hunt based on physical morphology. Men and women can both hunt, there is little doubt, but do men and women equally want to? If as a child you didn’t want to roam through the neighborhood shooting birds and squirrels (and women did this much less than men) was this because you were conditioned by gender roles to feel that way or might men and women have differences in desire driven by human evolution?

If as a man or a woman you don’t want to kill a rabbit (or if you do), ask yourself why. Think about how it makes you feel. How might those feelings have been adaptive in a past human environment? For example, is the desire to nurture a cute animal a byproduct of the desire to nurture a human infant — this would facilitate the survival of offspring. Is the desire to kill a feeling that would have facilitated hunting or human physical conflict? This, too, could be beneficial.

References

Anderson, A., Chilczuk, S., Nelson, K., Ruther, R., & Wall-Scheffler, C. (2023). The Myth of Man the Hunter: Women’s contribution to the hunt across ethnographic contexts. PLoS one, 18(6), e0287101.

Eals, M., & Silverman, I. (1994). The hunter-gatherer theory of spatial sex differences: Proximate factors mediating the female advantage in recall of object arrays. Ethology and Sociobiology, 15(2), 95-105.

Halpern, D. F., & Collaer, M. L. (2005). Sex differences in visuospatial abilities: More than meets the eye. The Cambridge handbook of visuospatial thinking, 170-212.

Lombardo, M. P., & Deaner, R. O. (2018). On the evolution of the sex differences in throwing: throwing is a male adaptation in humans. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 93(2), 91-119.