Human Status Hierarchies: Dominance and Prestige

The dual strategies theory of status in evolutionary psychology and anthropology proposes two mechanisms by which status is acquired: prestige and dominance (Henrich & Gil-White, 2001; Maner, 2017).

Dominance hierarchies are formed and maintained through physical force (or the threat thereof). Gorillas and baboons are primates who form social hierarchies largely through the dominance pathway. Physical aggression and intimidation allow dominant males to monopolize access to females. Male rivals can be beaten, bitten, and shouted into submission, driving them away or placing them in a subordinate position.

Human males, too, defer to physical dominance. It is likely that the behavior and social structure of our early ancestors resembled our modern ape relatives more closely than today. Physical dominance may have been more relevant then. We still see male-male deferential behavior in response to cues of dominance as a result of our evolutionary history. Contest competition in our ancestors — physical fights between males — has shaped who we are now and produced sexual dimorphism in our species (Puts et al., 2015; Hill et al., 2017)

Men who are physically stronger are perceived as more socially dominant (Windhager et al., 2011), as are men with deeper voices (Puts, 2007; Wolff & Puts, 2010). Further, these cues are honest signals; facial and bodily masculinity predict winning physical competitions for men (Kodsmeyer et al., 2019). Traits associated with physical dominance also predict mating success for men (Hodges-Simeon et al., 2011).

However, physical dominance is less relevant today than the second pathway: prestige. While our distant ancestors resembled our current ape relatives more, we have two million years of evolution out of the Pleistocene behind us. More recent years in the evolutionary time frame have seen a selection for complex social behavior, language, less robust physiques, prosociality, long-term monogamous pair bonding over polygyny, a high degree of cooperation, and relative dearth of interpersonal physical conflict.

To illustrate on a personal level, the average person has never been in a serious physical fight. You cannot acquire a home by taking a house from someone else. A promotion will not be granted if you beat up your boss. If your wife runs off with another man, pummeling him into submission is unlikely to return her to you.

Competitions of dominance are still relevant, but competitions of prestige dominate the modern Western world.

We even reinforce this with the law. Even when inclined to do so, few people engage in physical violence due to the consequences. The immediate environment shapes our behavior, such that battles of physical dominance are penalized and avoided. As a result, physical fights are most frequent in the lowest socioeconomic strata and the criminal underclasses.

Dominance hierarchies, in many ways, are more clear prestige hierarchies. The ability to pummel someone into the ground is hard to fake. It is an honest signal. It also carries a high degree of risk. There are painful consequences for engaging in physical dominance contests, especially for the losers. This also makes shows of dominance a costly signal.

Status in prestige hierarchies isn’t always unclear, but can be more ambiguous. This is because the degree of status that you have is that which others give to you.

The invention of currency gave us one prominent indication of status. If you give value to others you receive money and this tracks your status. Titles, such as those bestowed by royalty or a formal institution, are status signals. If sir or doctor precedes your name, others perceive you as having higher status. Further, these titles accord you additional social privileges and rights (such as being allowed to perform surgery). The job you hold, similarly, is a status signal. For example, blue collar jobs are perceived as lower in status (even in cases where they make more money).

That something may simultaneously confer and diminish status may seem a paradox, but this is because human status hierarchies are nested. Modern society is complex. What moves you up one hierarchy may move you down another. To illustrate, the decision to enter trade school over the university may result in a higher income, which brings status, but a lower level of formal education, which is seen as an important marker of status signal to many.

Another way to imagine status hierarchies is as a series of ponds and lakes. You may recognize this as the big fish in a small pond metaphor. The best football player in high school may have been quite a star, but be mediocre on his city’s team and not skilled enough to make the national team. Similarly, selling the highest quality methamphetamine may make you very popular with drug addicts, but not enhance your status at all in your run for the mayor’s office.

The point is that what is high status to one group is not necessarily perceived as high status to others and in some cases what is status-enhancing in Group A is status-diminishing in Group B.

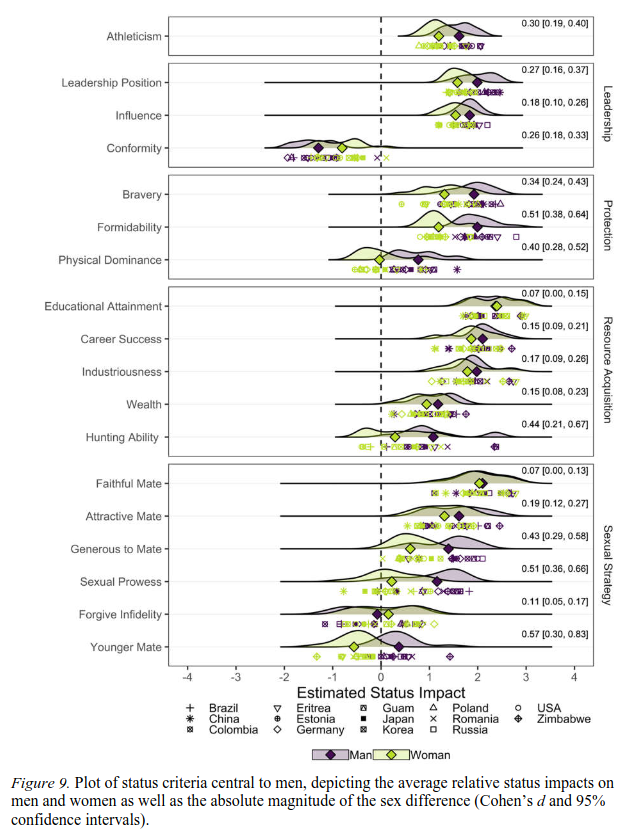

This is not to say that there are no human universals of status, or at least that some markers of status are not so widely recognized that they might as well be universal. To illustrate some shared human status criteria, we can look to the research of David Buss (2020) using a large intentional sample.

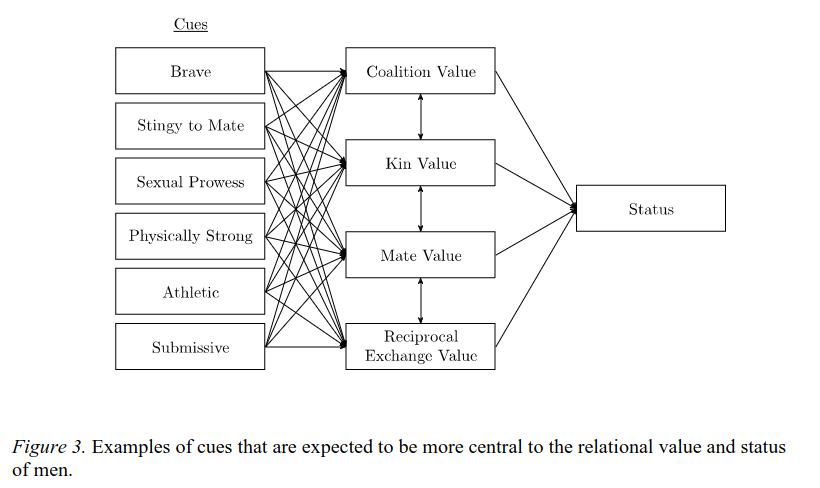

Below are two images, the first showing status domains expected to be especially relevant for men and the second showing the effects of status criteria for men.

Take particular note of the following status domains: sexual prowess, mate value, having a faithful mate, and having an attractive mate.

Costly Signals, Honest Signals, Hard To Fake Signals

The idea of an honest signal was touched upon briefly above. Perceptions of facial and bodily dominance predicted actual victories in physical competitions (Kordsmeyher et al., 2019). If someone looks a lot like they can beat you up there is a good chance that they can.

Given that all traits are heritable, honest signals of fitness-enhancing traits can be sexually selected for.

Costly signals and hard to fake signals are what they sound like; they also overlap with honest signals. A costly signal is, literally, hard to fake (but not all signals that are hard to fake are costly). For example, donating one million dollars to a charity is both costly and hard to fake. A donation imposes a cost on the giver (they lose the money) and it signals that they have so much money that they can afford to give away large sums. The use of such costly signals may have evolved to acquire social status and mates (Gintis et al., 2001; Barclay & Van Vugt, 2015). Indeed, among many hunting and gathering groups, costly and prosocial signaling is crucial for the acquisition of status (Bird & Power, 2015).

The use of the term honest signal is not intended to imply a deliberate act of honesty, but rather that the signal conveys accurate information. Attributing honesty and dishonesty to animal behavior may be too anthropomorphic (although animals are capable of deception). Human beings, however, are capable of deliberately producing fake or dishonest signals of status. Given that so much how we convey information is through words, we can simply lie.

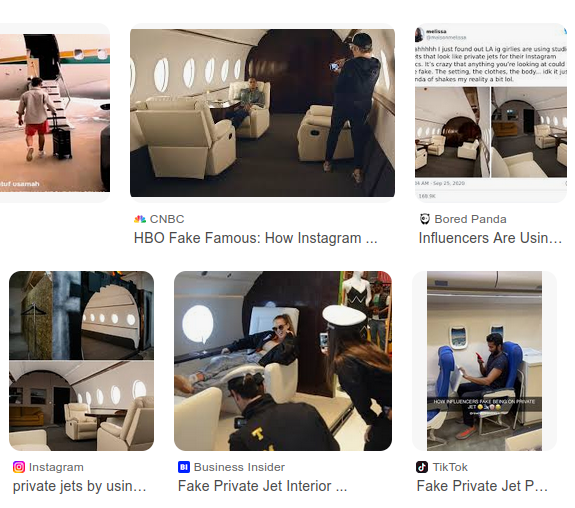

For example, someone may claim to be a doctor on their Tinder profile when they are not in the hopes that it will make them more attractive to potential mates. Influencers on social media may pose in fake private jets, or in front of luxury cars, that they do not own. They want to convey that they are high status or wealthy when they really are not. Standing next to expensive items conveys that signal.

The use of deceptive signals through images works so well that it is an applied aspect of marketing. Toothpaste ads use models with veneers and models who have their teeth digitally enhanced to be more white.

Red pill podcasters have their own version of this, too. The most popular format of these podcasts has become the roundtable discussion. OnlyFans creators and other women involved in the sex trade are brought on shows to argue or to just sit there looking bored. It is a mutually beneficial partnership. Red pill content creators get to present themselves adjacent to women. OnlyFans creators get a boost in subscriptions when they appear on red pill podcasts (a phenomenon that OnlyFans performer Jazmen Jafar has called her “red pill simps”).

In other words, influencers who want to sell the image that they are wealthy pose in fake jets, toothpaste companies sell toothpaste with fake teeth, and podcasters sell relationship expertise with fake female attention.

Words, as a signal, are even easier to fake. Anyone can claim anything. Although lies do incur costs — being perceived as a dishonest person is status diminishing — this requires that the lie is detected.

Nonetheless, human beings lie frequently and this is evidence enough that lies work at least some of the time. That we have a psychology adapted for the occasional telling of lies shows that lies provide benefits often enough for lying behavior to persist.

Further, people are often motivated to believe lies told by in-group members, or at least to ignore lies told by in-group members. Referring back to the research of David Buss (2020), supporting the in-group is status enhancing and defecting from the in-group is status diminishing. It behooves people to play along with the fictions of their own in-group. This is part of why so few people are inclined to call out dishonest politicians within the party they support. We tend to ignore, even promote, the lies and fictions of those on our team.

Given the information up to this point, we can say a few things about status:

- If people lie to enhance status, they will lie about things that are relevant to the hierarchy they want to achieve status within.

- For men, sexual and romantic success enhances status. For dating experts, even moreso.

- In-group members will play along with the status-enhancing lies of their fellows.

Knowing what behaviors are status enhancing will tell you what men and women are inclined to lie about.

Romantic And Sexual Success Are Male Status Cues

Robust signals of male status are romantic and sexual success. This, too, can be understood from an evolutionary perspective. If higher status males were more likely to have, or monopolize, access to mates then having an abundance of mating success is an indication of status. This remains true even if you don’t take an evolutionary perspective. If we simply see a pattern in our own lives where high status is associated with mating success, then we may also begin to infer status from mating success.

Given the link between status and mating success, it should be no surprise that men lie about their sexual and romantic achievements. In a recent poll, I asked 1,518 men and women if they had ever experienced a man lying about or exaggerating his sexual conquests. 70% of men and 71% of women reported that they had.

Jonason (2007) found that men perceived a high sexual partner count as status enhancing in men. A replication and extension (Jonason & Fisher, 2009) produced the same result. Additionally, men who perceived having more sexual partners as status enhancing were also more likely to report having more sexual partners. Perceptions of status fully mediated the relationship between gender and self-reported sexual partner count. In other words, when status-based male exaggerations were accounted for there was no longer a difference in the number of partners reported by men and women. (I was also able to replicate the same association between status beliefs about promiscuity and self-reported partner count in my own research.)

When reporting their own motivations for having had sex, men were more likely than women to say it was for an increase in status (Regan & Dreyee, 1999). Men have some self-awareness about the relationship between sex and status; it is enough to seek out sexual encounters for status (or lie about it). As status cues are internalized, men may also seek sexual experiences to affirm their own status to themselves. In my own research, I found that men were more likely than women to report that validation was their motivation for having casual sex.

In an experiment by Fisher (2007), male and female participants were instructed to report how many past sexual partners they had. In one condition, a man administered the survey and in a second condition a woman administered the survey. Women’s reports did not differ between conditions, but men’s reports did. Men reported significantly more sexual partners when a woman administered the survey and when men were told that women had more sexual partners on average than men did. By telling men that women had more partners (a status cue to men), men were more inclined to exaggerate their own sexual experience. It was a sexual “keeping up with the Joneses” effect.

The Manosphere, Pick-Up Artists, and The Red Pill: Where Are The Receipts?

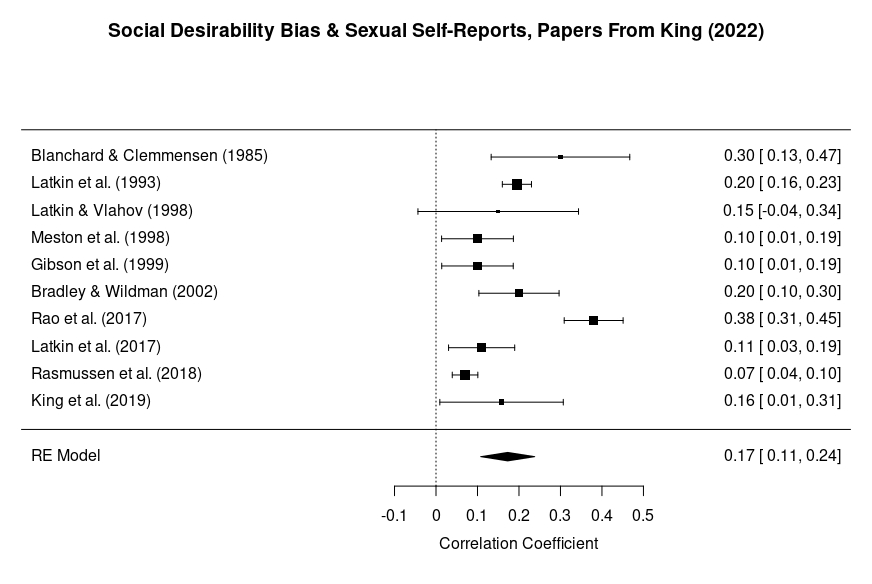

Biased reporting of sexual behavior in research contexts consistently shows real, but small, effects. The research described in the previous section is no exception. This is true for both men’s upward exaggerations and women’s downward exaggerations. To illustrate, I recently conducted a meta-analysis of papers cited in King’s (2022) review of social desirability bias in self-reports of sexual behavior. The pooled effect size was only .17.

However, reports on an anonymous survey aren’t much of a signal in the first place. No one in your status hierarchy can link your response to you. Further, if the replication crisis has taught us anything, it is that research on unconscious motivational processes is weak (see Ulrich Schimmack’s False Psychology Glossary). There is no credibility to claims that large exaggerations exist in sexual self reports, at least in research paradigms.

For naturalistic conditions, however, all bets are off. We really don’t know how much men or women lie, nor when they will lie more. Given that this is a real effect, we should expect lies to be larger in real-life settings where the reward for lying is high. Small exaggerations upward on surveys, for men, may become motivated boasting on the Internet. Similarly, hiding past sexual partners may be infrequent on surveys for women, but if you ask a woman on a first date across the dinner table how many people she has had sex with, she may not be inclined to tell you the truth.

In other words, real-world claims from men about their past sexual conquests is an easy to fake signal. You can pretend to be Giacomo Casanova and no one will know, except for perhaps close friends or family. Certainly, no one on the Internet will know for sure. This makes the Internet a fruitful ground for anyone who wishes to promote themselves as an expert on sex, romantic relationships, and the behavior of women: all backed up with nebulous claims of “lived experience.”

This has not gone unnoticed, at least by some denizens within pick-up artist communities. The phrase “show receipts” has been used by in-group skeptics to ask for evidence that community members and influencers are having sexual or romantic success. However, these demands for verification are remarkably infrequent. Most men in these communities are inclined to simply believe the stories others tell. There is an entire ecosystem of completely anonymous social media accounts selling pick-up booklets and courses. Remember, people are motivated to trust, believe, and not question the in-group.

Influencers and podcasters who are not anonymous don’t tend to be much better. Beyond the occasional blurry first-date photo or Tinder chat, there is little evidence that these men have any exceptional dating experience. In the “infield” videos of some influencers — where they record themselves flirting with women — it almost always stops there. However, getting a woman to speak with you, match with you on Tinder, or even go on a date is poor evidence of sexual or romantic success. At best all they have demonstrated is that they are not literal incels; at worst they are actually showing that they cannot get far enough to form a lasting sexual or romantic relationship.

Hard-To-Fake Signals of Romantic and Sexual Success

It has always been the case that men who are married or in committed relationships are higher on almost every metric of mate value, from physical attractiveness to psychological traits. Across historical periods and cultures, having a wife has been a clear distinction between men of low and high status. Today, individuals of a higher class or socioeconomic status are still more likely to marry and less likely to get divorced than lower class individuals (Karney, 2021). To illustrate this at the extreme tail of the world’s highest status and most powerful men, we examined the world’s 50 wealthiest men from the Forbes billionaires list. 74% of top billionaires were married (and half of the remaining 26% had only recently divorced), in contrast to just 45% of all Americans.

We select mates who are similar to us across most traits (physical and psychological). This is called assortative mating (for a classic review see Buss, 1985). Higher mate value is also associated with stronger assortative mating (individuals of higher mate value select partners who are even more similar to themselves), given that more desirable individuals have more “purchasing power” and are more likely to be desired by high value members of the opposite sex (Conroy-Beam et al., 2019).

This gives us two robust and hard to fake signals of status and mate value:

- Having a committed romantic partner at all.

- Having a committed romantic partner who is desirable, attractive, or otherwise high in mate value themselves.

In fact, the mate value of a female partner is a very good predictor of a man’s own mate value (and vice versa), correlating at .5 (Salkicevic, 2014). Male promiscuity, on the other hand, is a poor predictor of male mate value, given that more promiscuous men make downward selections in mate choices, and male promiscuity is associated with all of the same markers of low mate value that female promiscuity is associated with.

We can also look at some examples of how sexual and romantic success as status signals vary with social class. Rap music reflects the subcultures of a lower socioeconomic class in the United States (which is not to say that it isn’t enjoyed by all types of people). It is a musical genre of the streets, and the subgenre of gangsta rap reflects a further criminal underclass subculture. As such, gangsta rap tells you the values of its milieu. The type of status-signaling that occurs within its lyrics demonstrates what is valued within the status hierarchy of that subculture. One of the most popular themes is promiscuity — rapping about how many hoes you have.

Conversely, an upper class phenomenon in mate selection is that of trophy wives. Men in positions of high status or power will marry women of exceptional physical attractiveness (many of whom also come from affluent backgrounds themselves).

Why do lower class men brag loudly about having casual sex with hoes while upper class men quietly marry beautiful women? Both signal status within their respective hierarchies (although status is not the only reason men select such mates). However, men of low status have fewer status signals to display. To tell someone how many hoes you get is an easy to fake signal. You can just make it up. You can pay some women to appear in your rap video (similar to red pill podcasters asking OnlyFans creators onto their shows).

To marry a supermodel, however, is hard to fake. There is little need to tell other men, “My wife is beautiful.” Other people can use their own eyes and see that.

Dyadic Displays, Mate Choice Copying, and Intrasexual Competition

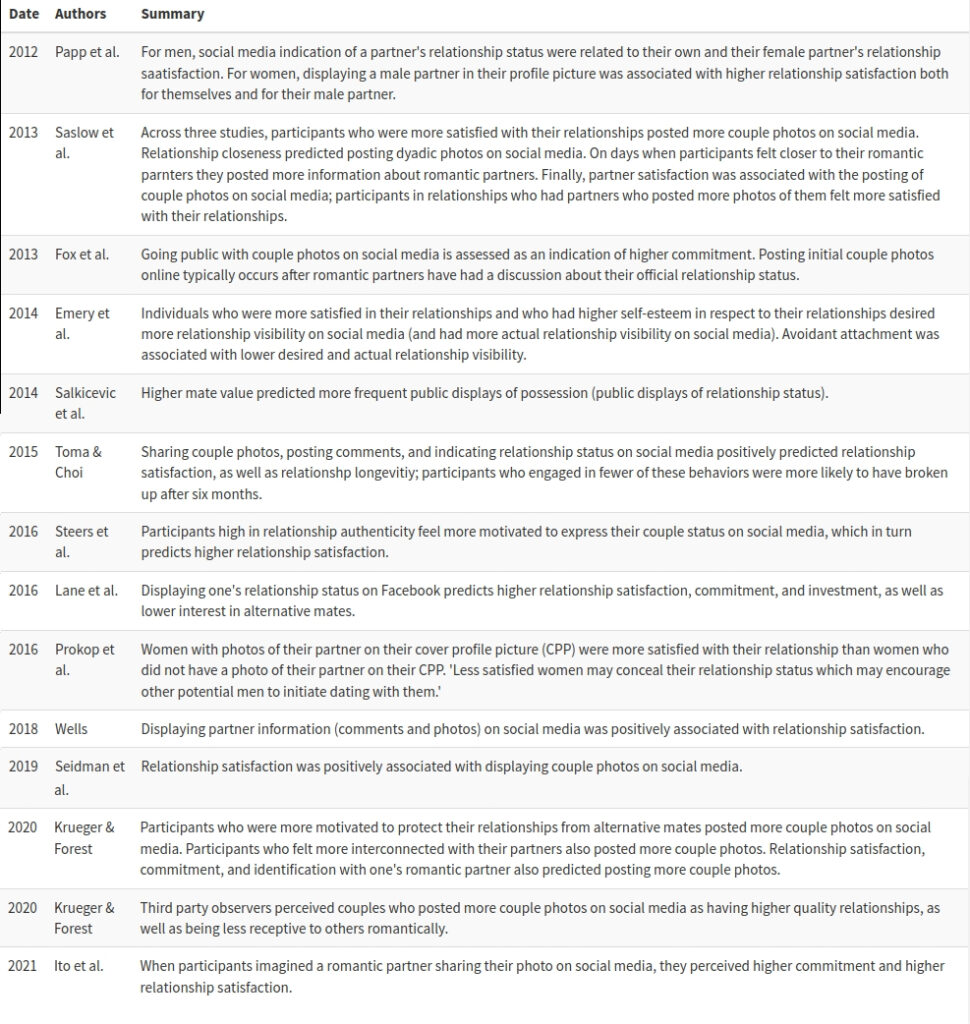

Mate choice copying, or preselection, refers to selecting mates based on their previous selection by conspecifics. This tendency has been demonstrated in both human and nonhuman animals. When an individual is chosen by someone of the opposite sex they are perceived as more desirable by members of the opposite sex.

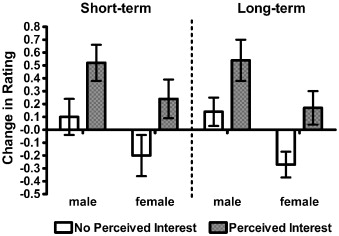

It’s important to note that this doesn’t occur in all instances. For example, one study presented photos of men with a female date and asked women to rate the attractiveness of the men. Men were rated as more attractive only in the condition that the female date was herself more physically attractive (Waynforth, 2007).

In another study, participants observed the result of a speed-dating experiment (Place et al., 2010). When speed-daters received little interest from matches, observers also desired them less. When they received more interest, observers desired them more.

Both of these represent relatively hard to fake signals of opposite-sex interest. As far as I am aware, no research has demonstrated a preselection or copying effect resulting from bragging about past sexual partners. I mention this, because I have seen men in the manosphere mistakenly claim that women like a high “body count” in men because it demonstrates preselection. In fact, research shows the opposite: a high “body count” is perceived negatively by both men and women. Further, women who have had fewer sexual partners also desire men with fewer sexual partners — and this is reflected in their actual mate choices, such that we see correlations between partner “body count” and sociosexuality in relationship partners.

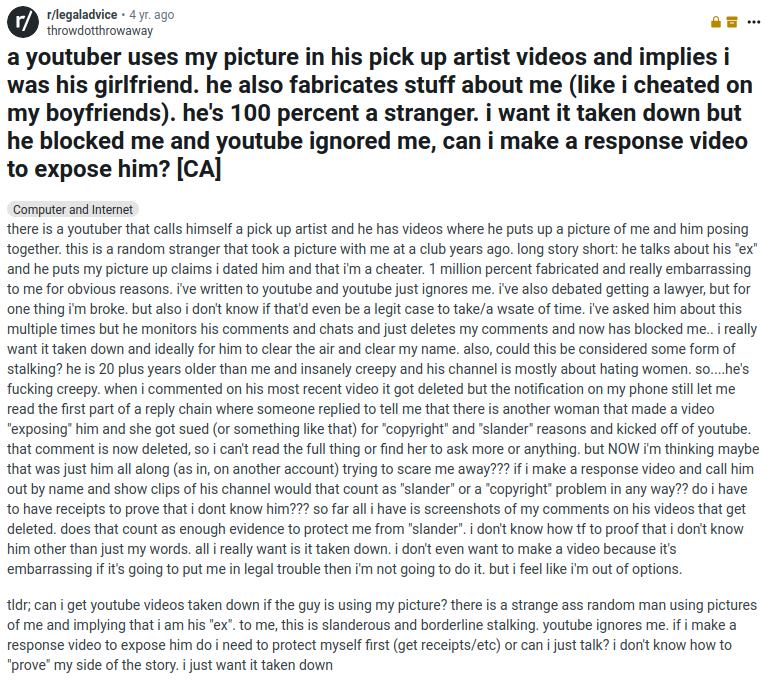

I should also note that I have seen pick-up artists, presumably familiar with this literature, recommend that men use pictures standing next to attractive women in their dating app profiles. This may have a positive effect, but this also illustrates how standing next to a woman isn’t that hard to fake after all. Pick-up artists may also do this themselves to signal status to other men:

A dyadic display refers to a public display of affection, desire, or relationship commitment. Holding hands or having a wedding ceremony are both examples of dyadic displays. These may be intentional or unintentional signals. Intentional dyadic displays can be used for different purposes. If a woman is looking at you in the bar, your girlfriend might put her arms around you to signal “he is mine.” As such, dyadic displays also serve as a form of mate guarding. Dyadic displays also signal status. Men or women who are proud or happy to be seen with their romantic partners will show them off more.

Dyadic displays are also costly signals. This is because they limit further mating opportunities. Dyadic displays communicate unavailability and commitment. Third party observers also actually perceive dyadic displays this way and are less likely to approach men or women who they know are in relationships or sexually unavailable.

A recent poster from a red pill account on Twitter/X gave his opinion on the matter: women perform dyadic displays when they are unsure of a potential mate. These, somehow, signal a lack of “genuine desire.”

As I have written in the past, the red pill is a folk psychology where men opine about the inner psychological workings and feelings of women. Despite the maxim, “Watch what women do, not what they say,” when women choose a mate and display them for the entire world to see they don’t seem very inclined to recognize the signal, or what women do.

This lay theorizing is not a very good explanation. Fortunately, we know it’s a bad explanation because evolutionary psychologists have examined it at some length. As much as the red pill claims to be grounded in “evolutionary psychology,” they often don’t seem to have a very good evolutionary understanding for why men and women engage in certain mating and relationship behaviors.

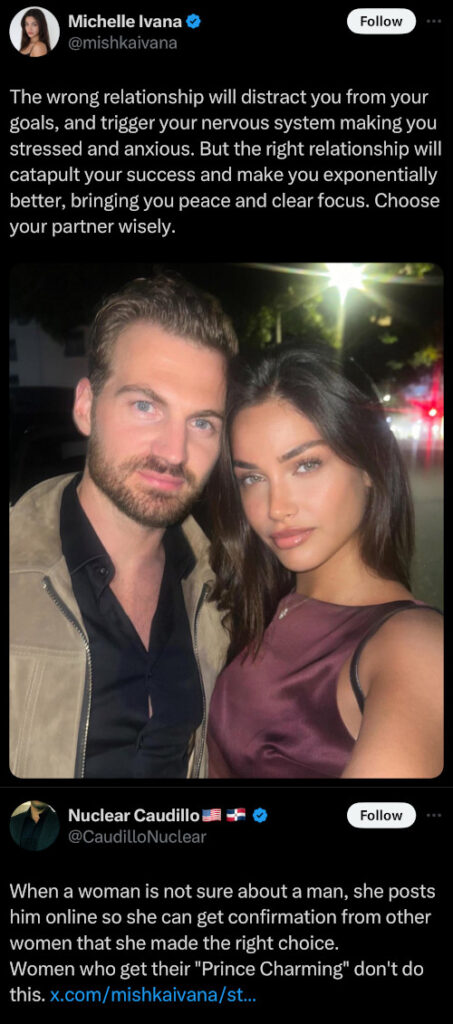

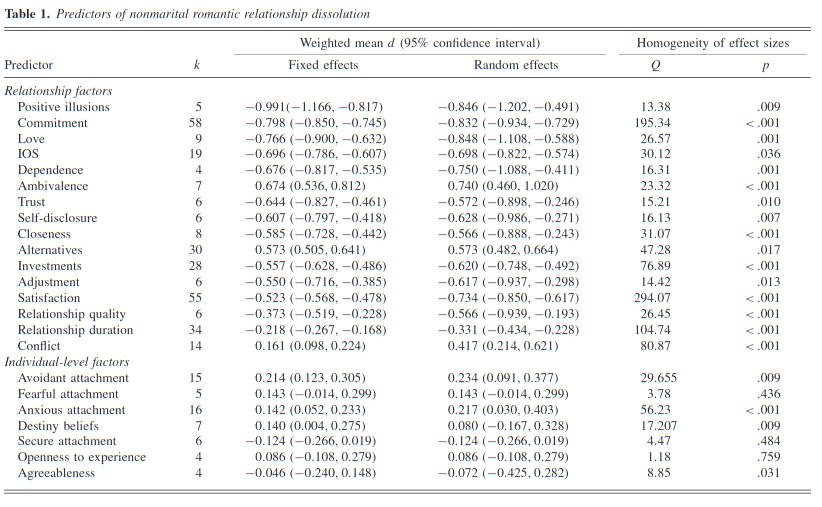

Below is a table with a summary of relevant research findings on sharing dyadic displays on social media. Contrary to this poster’s speculation, women share dyadic photos on social media when they are more committed, more invested, have higher relationship satisfaction, and have male partners with higher mate value. Further, sharing photos online predicts actual relationship outcomes: couples who did not share dyadic photos were more likely to break up. Couples who share photos online are also less receptive to romantic alternatives and more motivated to protect their mates from alternatives (which is also associated with mates having higher mate value, see Miner et al., 2009; Salkiceiv et al., 2014).

If you have read this far and you are thinking to yourself, “But this is what women say; we must watch what women do,” let me remind you that all of these reports predict actual relationship outcomes. Below are the results from a meta-analysis by Le et al. (2010). Not only do self-reports of relationship satisfaction predict who will break up, but they are very strong predictors of who will break up in many cases:

This is, perhaps, devastating for much manosphere ideology, because what people do in fact is predicted by what they say. At least as far as staying in a relationship is concerned.

Here we come full circle. High mate value in men is associated with having a romantic partner, having an attractive romantic partner, and public displays of commitment or relationship status.

Given this, we might expect the “high value” men of the manosphere to show off their attractive relationship partners. Even better, we might expect their high value partners to show them off. Yet, this is very rare to see. The women they are involved with, be it in committed relationships or as casual sex partners, are ghosts.

We can go back to the original post and read between the lines. Why would he believe that it is true? Why do men denigrate other men, the romantic partners of others, or the relationships of others?

As I have written about before, this is intrasexual competition. Proximate emotions associated with intrasexual competition are envy and jealousy (Morgan et al., 2022; Jonason et al., 2023). A conventionally attractive woman has signaled that she has chosen another man. The feedback this couple received was overwhelmingly positive (save for manosphere comments), which is status enhancing. No shortage of women praised the attractiveness of this man and this couple. They sent a very hard to fake signal. If you watch what women say, rather than speculate about how they secretly feel, this woman chose someone who was not a part of the manosphere in-group. She was putting him on display, but very few manosphere influencers have women putting them on display.

In other words, if you saw this comment and thought “he is jealous or envious,” you would be right.

The scale created by Jonason et al. (2023) lists behaviors, thoughts, and emotions associated with intrasexual competition: “I can’t stand it when someone else is more attractive than me,” “I look for negative traits in attractive others,” and “I enjoy it when women pay more attention to me than others.” Given that manosphere influencers are generally low in physical attractiveness (see how women rate them) and also often lack attractive romantic partners, this explains why verbal denigration of others is so frequent in their discourse.

It may seem strange to imagine that, in a world of 7.95 billion people, we would become envious or intrasexually competitive in respect to the relationships of others online. It helps to remember that the environments our psychology evolved in consisted of small groups. We respond to the wins, losses, and status signals of strangers online the same way that we might had they been real-life members of our community. If you have ever noticed that social media feels like high school it is because the same dynamics that occurred within that close peer group continue to play out with strangers online. Just as the less popular kids made fun of the jock-and-cheerleader couple out of jealousy, we see people react the same way to strangers and celebrities online who signal their wins (but mostly from people who don’t have similar wins themselves).

Conclusion

Influencers, by design, are attempting to rise in a status hierarchy. For many dating influencers, particularly those whose expertise is derived from an appeal to their own supposed experience, this means convincing others that they are sexually or romantically successful. In the absence of honest or hard to fake signals they will do what they need to do; they will tell you how successful they are.

It’s up to you if you believe them or not. For in-group members, or individuals who have already decided to become fans and followers, we shouldn’t expect much in the way of skepticism or objectivity. They will promote those stories because they are motivated to do so. To critique the in-group is status diminishing. Men in the red pill will not come out and say, “You know, I have seen you talk about women a lot, but you have been single for ages and I haven’t seen any real indication that attractive women like you.”

It is enough that the in-group shares an ideology and that influencers say what other men want to hear. For example, people don’t binge watch YouTube videos about bigfoot experiences because they think the storytellers have proof that bigfoot is real. They just like the stories and they want to believe.

Nonetheless, there is ample reason for everyone else to be skeptical. As described throughout this article, there is little in the way of hard to fake signals coming from the manosphere. There are “no receipts,” to use the lingo of more skeptical pick-up artist community members. The high intrasexual competitiveness of manosphere communities is also a tell, because this reflects a “punching up” at others who are more romantically or sexually successful than they are.

The data I have collected on manosphere communities also doesn’t paint a picture of exceptional success. Not only are manosphere influencers perceived as low in physical and vocal attractiveness by women, but average men in the manosphere don’t seem to be outperforming average men outside of the manosphere on romantic and sexual metrics.

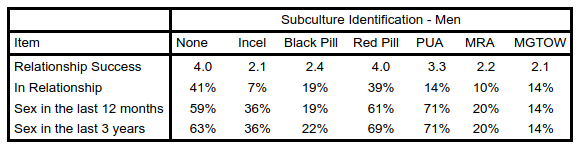

In an early survey from Feb 2023, I found no significant differences between red pill men, pick-up artists, and men who were none of the below groups on relationship success, being celibate over the last 12 months, and being celibate over the last 3 years. Pick-up artists were significantly less likely to report being in a successful relationship than men who were not members of one of the below communities.

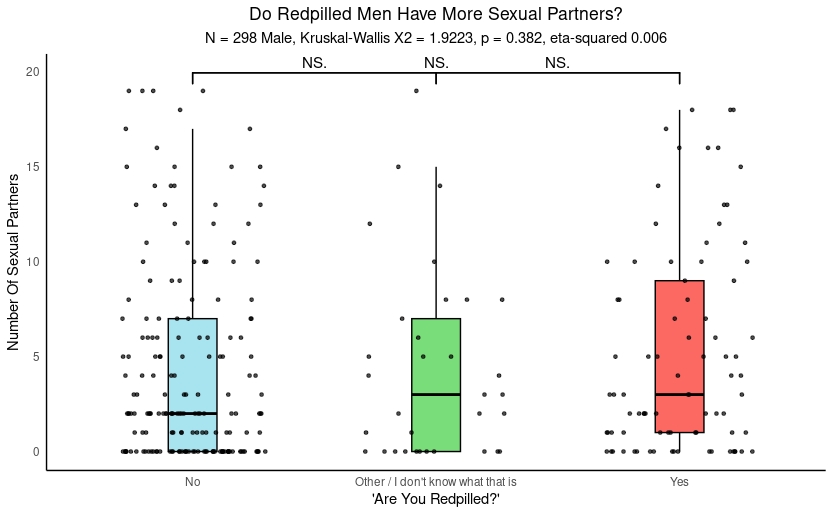

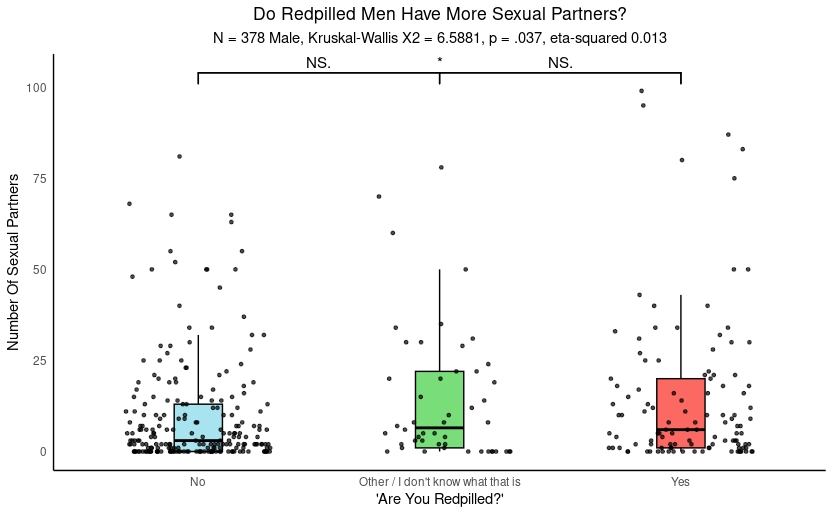

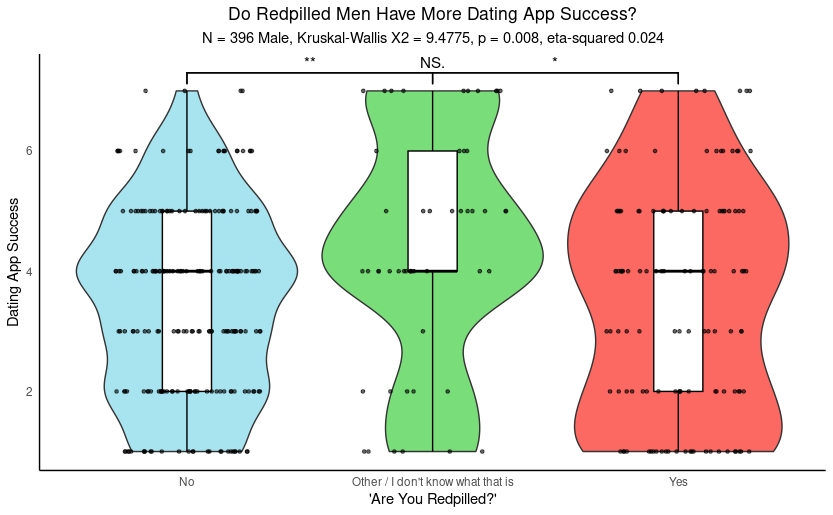

In a second survey from Jan 2024, men indicated if they were red pilled or not and reported their lifetime number of sexual partners as well as their success on dating apps. Men who were red pilled did not have more lifetime sexual partners, nor were they more successful on dating apps.

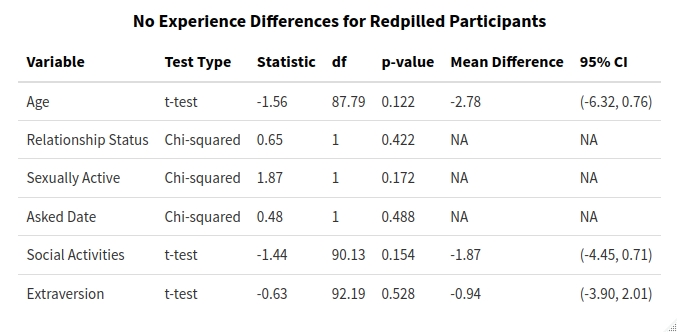

In the most recent survey from Aug 2024, participants were assessed for Big Five extraversion, the extent to which they participated in in-person social activities (e.g. going to bars, clubs, hobbies, and events with women), committed relationship status, being sexually active over the past year, and having asked a woman on a date in the past year.

Red pilled men were not more extraverted nor more likely to engage in the kinds of in-person social activities associated with sexual outcomes. Red pilled men were also not more likely to be in a relationship, be sexually active, or to have asked a woman on a date in the past year.

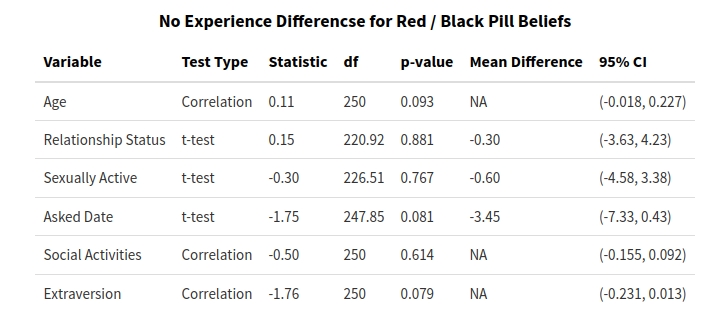

A scale measuring red and black pill beliefs was also administered; scores on this scale did not predict any of the preceding variables, either.

The manosphere is not a homogenous group; it consists of self-improvement gurus, dating “experts,” incels, “men’s rights activists,” and more. However, interacting with the dating-centric wing of the manosphere — as well as collecting data from its members — has led me to believe it is largely a facade. From men who claim to be experts on “evolutionary psychology” who regularly misrepresent the field to anonymous pick-up artists promising you that they can teach you how to attract models, it’s hard to see it as anything but mostly fake.

Instead, what we see is a lot of male-to-male status signaling. These are overwhelmingly male communities (which is also a sign that women do not like them very much) telling stories that a male fringe wants to hear. Their status signals, or claims of sexual success, are easy to fake. It is little different from boasting about “that hot girl I totally fucked last night, bro.”

References

Barclay, P., & Van Vugt, M. (2015). The evolutionary psychology of human prosociality: Adaptations, byproducts, and mistakes. The Oxford handbook of prosocial behavior, 37-60.

Bird, R. B., & Power, E. A. (2015). Prosocial signaling and cooperation among Martu hunters. Evolution and Human Behavior, 36(5), 389-397.

Buss, D. M. (1985). Human mate selection: Opposites are sometimes said to attract, but in fact we are likely to marry someone who is similar to us in almost every variable. American scientist, 73(1), 47-51.

Buss, D. M., Durkee, P. K., Shackelford, T. K., Bowdle, B. F., Schmitt, D. P., Brase, G. L., … & Trofimova, I. (2020). Human status criteria: Sex differences and similarities across 14 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(5), 979.

Conroy-Beam, D., Roney, J. R., Lukaszewski, A. W., Buss, D. M., Asao, K., Sorokowska, A., … & Zupančič, M. (2019). Assortative mating and the evolution of desirability covariation. Evolution and Human Behavior, 40(5), 479-491.

Emery, L. F., Muise, A., Dix, E. L., & Le, B. (2014). Can you tell that I’m in a relationship? Attachment and relationship visibility on Facebook. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(11), 1466-1479.

Fisher, T. D. (2007). Sex of experimenter and social norm effects on reports of sexual behavior in young men and women. Archives of sexual Behavior, 36, 89-100.

Fox, J., Warber, K. M., & Makstaller, D. C. (2013). The role of Facebook in romantic relationship development: An exploration of Knapp’s relational stage model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(6), 771-794.

Gintis, H., Smith, E. A., & Bowles, S. (2001). Costly signaling and cooperation. Journal of theoretical biology, 213(1), 103-119.

Henrich, J., & Gil-White, F. J. (2001). The evolution of prestige: Freely conferred deference as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evolution and human behavior, 22(3), 165-196.

Hill, A. K., Bailey, D. H., & Puts, D. A. (2017). Gorillas in our midst? Human sexual dimorphism and contest competition in men. In On human nature (pp. 235-249). Academic Press.

Hodges-Simeon, C. R., Gaulin, S. J., & Puts, D. A. (2011). Voice correlates of mating success in men: examining “contests” versus “mate choice” modes of sexual selection. Archives of sexual behavior, 40, 551-557.

Ito, K., Yang, S., & Li, L. M. W. (2021). Changing Facebook profile pictures to dyadic photos: Positive association with romantic partners’ relationship satisfaction via perceived partner commitment. Computers in Human Behavior, 120, 106748.

Jonason, P. K. (2008). A mediation hypothesis to account for the sex difference in reported number of sexual partners: An intrasexual competition approach. International Journal of Sexual Health, 19(4), 41-49.

Jonason, P. K., & Fisher, T. D. (2009). The power of prestige: Why young men report having more sex partners than young women. Sex Roles, 60, 151-159.

Jonason, P. K., Czerwiński, S. K., Brewer, G., Cândea, C. A., De Backer, C. J., Fernández, A. M., … & Fisher, M. L. (2023). Three factors of the Intrasexual Competition Scale?. Personality and Individual Differences, 213, 112312.

Karney, B. R. (2021). Socioeconomic status and intimate relationships. Annual review of psychology, 72(1), 391-414.

King, B. M. (2022). The influence of social desirability on sexual behavior surveys: A review. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(3), 1495-1501.

Kordsmeyer, T. L., Freund, D., Vugt, M. V., & Penke, L. (2019). Honest signals of status: Facial and bodily dominance are related to success in physical but not nonphysical competition. Evolutionary Psychology, 17(3), 1474704919863164.

Krueger, K. L., & Forest, A. L. (2020). Communicating commitment: A relationship-protection account of dyadic displays on social media. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(7), 1059-1073.

Lane, B. L., Piercy, C. W., & Carr, C. T. (2016). Making it Facebook official: The warranting value of online relationship status disclosures on relational characteristics. Computers in human behavior, 56, 1-8.

Le, B., Dove, N. L., Agnew, C. R., Korn, M. S., & Mutso, A. A. (2010). Predicting nonmarital romantic relationship dissolution: A meta‐analytic synthesis. Personal Relationships, 17(3), 377-390.

Maner, J. K. (2017). Dominance and prestige: A tale of two hierarchies. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(6), 526-531.

Miner, E. J., Starratt, V. G., & Shackelford, T. K. (2009). It’s not all about her: Men’s mate value and mate retention. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(3), 214-218.

Morgan, R., Locke, A., & Arnocky, S. (2022). Envy mediates the relationship between physical appearance comparison and women’s intrasexual gossip. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 8(2), 148-157.

Papp, L. M., Danielewicz, J., & Cayemberg, C. (2012). “Are we Facebook official?” Implications of dating partners’ Facebook use and profiles for intimate relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(2), 85-90.

Place, S. S., Todd, P. M., Penke, L., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2010). Humans show mate copying after observing real mate choices. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(5), 320-325.

Prokop, P., Morvayová, N., & Fedor, P. (2016). With or without you: does partner satisfaction and partner-directed violence influence the presence of a partner on women’s Facebook cover profile photographs?. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 32(2), 307-312.

Puts, D. A., Hodges, C. R., Cárdenas, R. A., & Gaulin, S. J. (2007). Men’s voices as dominance signals: vocal fundamental and formant frequencies influence dominance attributions among men. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28(5), 340-344.

Puts, D. A., Bailey, D. H., & Reno, P. L. (2015). Contest competition in men. The handbook of evolutionary psychology, 1-18.

Regan, P. C., & Dreyer, C. S. (1999). Lust? Love? Status? Young adults’ motives for engaging in casual sex. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 11(1), 1-24.

Salkicevic, S., Stanic, A. L., & Grabovac, M. T. (2014). Good mates retain us right: Investigating the relationship between mate retention strategies, mate value, and relationship satisfaction. Evolutionary Psychology, 12(5), 1038-1052.

Saslow, L. R., Muise, A., Impett, E. A., & Dubin, M. (2013). Can you see how happy we are? Facebook images and relationship satisfaction. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(4), 411-418.

Seidman, G., Langlais, M., & Havens, A. (2019). Romantic relationship-oriented Facebook activities and the satisfaction of belonging needs. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8(1), 52.

Steers, M. L. N., Øverup, C. S., Brunson, J. A., & Acitelli, L. K. (2016). Love online: How relationship awareness on Facebook relates to relationship quality among college students. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5(3), 203.

Toma, C. L., & Choi, M. (2015). The couple who Facebooks together, stays together: Facebook self-presentation and relationship longevity among college-aged dating couples. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(7), 367-372.

Waynforth, D. (2007). Mate choice copying in humans. Human Nature, 18, 264-271.

Wells, A. I. (2018). Attachment style and romantic satisfaction as predictors of relationship visibility on Facebook.

Windhager, S., Schaefer, K., & Fink, B. (2011). Geometric morphometrics of male facial shape in relation to physical strength and perceived attractiveness, dominance, and masculinity. American Journal of Human Biology, 23(6), 805-814.

Wolff, S. E., & Puts, D. A. (2010). Vocal masculinity is a robust dominance signal in men. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 64, 1673-1683.

2 comments

I find your research very interesting and I’m grateful a new generation of scientists and researchers addressing communities like the red pill directly. These kinds of things were harmful and mostly a waste of time when I was growing up, would have been nice if more people like you and Nuance pill were around back then.

Great piece as always.

Like you mentioned, the broader manosphere is a fairly eclectic mix, united (seemingly) by grievance alone. Someone like Walt Bismark on Substack feels like an extension beyond the explicitly sex/dating/gender focused subcultures that you identified. One piece I read from him said something to the effect of “it’s not difficult to accumulate a bodycount of 100+ if you live in a city and know how to talk to women.”

Which is obviously nonsense. I’ll grant that he may have a bodycount that high (though no receipts because he’s anonymous, go figure). But the showy nonchalance of saying it’s “not difficult” is quite calculated. He’s clearly a smart guy, smarter than the average redpill podcaster who pidgeonholes themself into the obsessive womanhater category. He seems aware that the goal for a successsful and well-hidden grift is to make your effortless successes with women implied. “I’m rich, I’m smart, I’m charming. Of course I’ve been with dozens of women; it’s easy when you’re a devil-may-care Patrick Bateman type. All you have to do is pay me a couple hundred to join my club and learn the secrets of my broad-scope rizz…”