Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

“Alpha Males” In Popular Culture

The “alpha male” is a muddled construct in our popular culture. I have seen very few good definitions of what exactly this is. Definitions of “alpha” tend to be circular and they define a vague idea with another vague idea. For example, an “alpha male” is a “high value male.”

Attempts at singular definitions also tend to exclude much of what we consider to be “alpha.” For example, is an “alpha” someone who is attractive to women? If so, this will exclude many high-status men — but is not “alpha” also being high in the social hierarchy? Depends on who you ask. As I wrote early on, some subcultures within the manosphere seem to use the term very differently from, say, how a primatologist might. “Alpha” is less status than it is vibe. An unattractive man of high status — indeed some of the most powerful men in the world, such as Jeff Bezos or Bill Gates — are not “alpha” because they do not have the vibe. Conversely, men of low status (e.g. criminals) are described as “alpha” merely for racking up low-quality casual sex partners.

For some manosphere influencers presenting a sort of faux evolutionary psychology, “alpha” means to have a fast life history strategy. Yet, research within evolutionary psychology shows that a slow life history is more closely associated with higher physical attractiveness, higher status, and higher mate value.

The Dark Triad (or now, Tetrad) has also been presented as “alpha.” There is a whole ecosystem of Pick-Up Artistry selling courses on how to “be more Dark Triad.” Yet the Dark Triad, too, is associated with lower mate value and even lower physical attractiveness.

The blackpill, a collection of beliefs espoused by incel and adjacent manosphere cultures, has a concept of “alpha” that overlaps with three clusters of traits: looks, money, and status. They place heavy emphasis on the superiority of looks in this triad, but it’s actually a reasonable starting point for a multi-dimensional concept of what an “alpha” is. Despite extreme beliefs, exaggerations, doomerism, and a tendency toward catastrophizing within this subculture they tend to be more scientifically informed on relationship science and evolutionary psychology than other manosphere subcultures.

Still, it doesn’t seem like anyone has an entirely clear concept on what an “alpha” is or how to identify one. This doesn’t mean that it’s a useless concept or that it doesn’t exist. Many human ideas and concepts don’t lend themselves well to simple, straightforward definitions. It’s a sort of “I know it when I see it” moment, to paraphrase US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart on “obscenity.”

“What is an alpha” might not be a good question (as Jordan Peterson likes to say; read it in his voice, “That’s not a good question.”). I won’t attempt to answer this question in full or give you a simple definition of an “alpha” here. Rather, a better question might be, “what does an alpha look like” or “what traits are associated with perceptions of alphas.” Those are questions we can begin to apply the scientific method to and examine in a more objective way.

Methods

238 survey participants were split between two experimental conditions. In both conditions, participants were presented with three vignettes describing a prosocial middle-class man, a wealthy “playboy,” and an antisocial “bad boy” with Dark Triad traits.

In Condition A, participants were told that the man was considered attractive to women and had an attractive wife or girlfriend. The vignettes were also accompanied by a photograph of a conventionally attractive man, selected from photos of male models.

In Condition B, participants were told that the man was considered unattractive to women and had a wife or girlfriend who was also considered to be unattractive. These vignettes were accompanied by photos of unattractive men.

Participants were randomly assigned to Condition A or Condition B and the sample was split into 121 and 117 participants for each condition.

Participants were asked to rate each vignette on how “alpha” it was, how “beta” it was, how high or low in status it was, how desirable as a long-term mate it would be to women, and how desirable as a short-term mate it would be to women. Participants also rated each vignette-photo combination on physical attractiveness.

All participants across both conditions additionally completed a 15-item survey, with 5 items coded as relating to physical attractiveness, 5 items coded as having money, and 5 items coded as status signifiers. Participants rated each item for how “alpha” it would make a man.

All participants also responded in their own words to describe what an “alpha” was to them for qualitative data.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

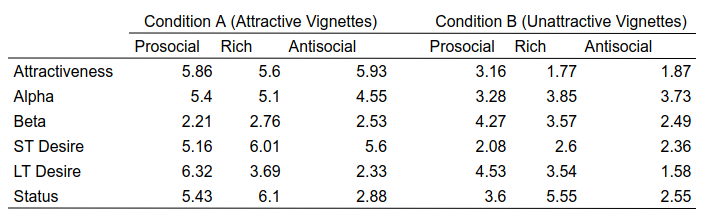

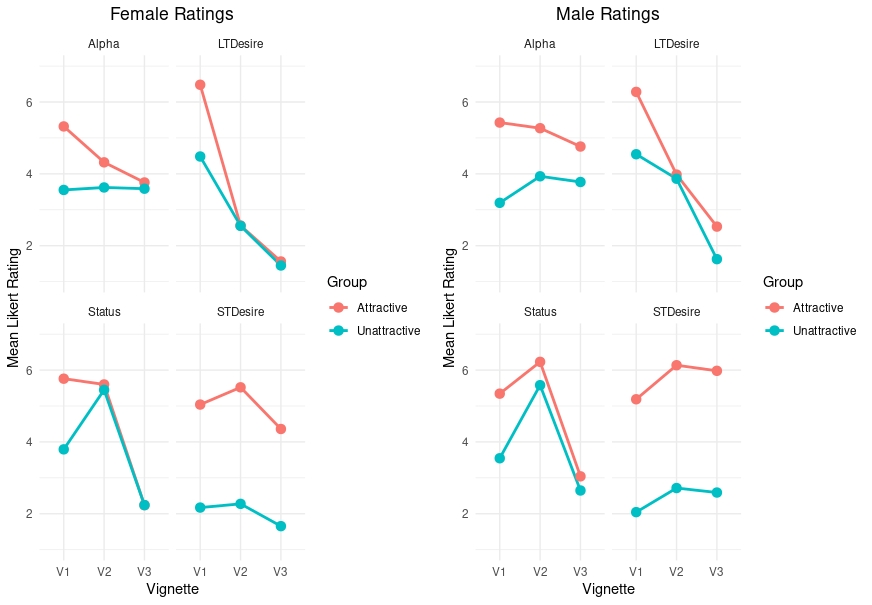

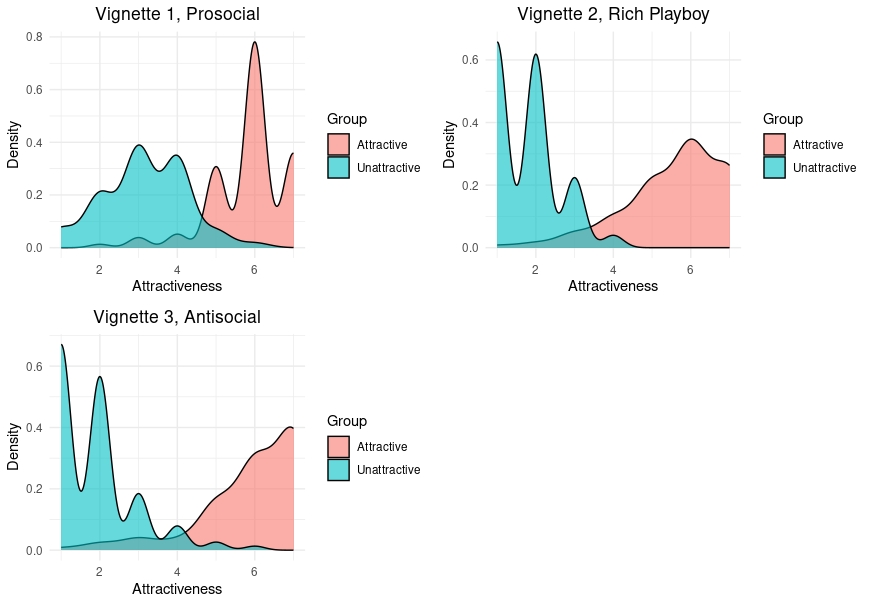

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of conditions and variables. Image 1 shows interactions between groups and variables. Across the three vignettes, never was an unattractive man rated as more “alpha” on average than an attractive man.

Long-term mating desire was highest for the attractive prosocial vignette. Interestingly, the unattractive prosocial vignette scored also higher in long-term mating desire than the attractive playboy and attractive antisocial vignettes. Antisocial vignettes scored especially low for long-term mating desire.

On status, attractiveness produced a large gap only for the middle-class prosocial vignette. Attractive and unattractive vignettes were perceived as similarly high in status for the rich vignette and similarly low in status for the antisocial vignette. The relatively larger gap for the prosocial vignette also appears in the first plot showing “alpha” ratings.

You could interpret this result such that being attractive is especially important for the “normal” man in how “alpha” they are perceived as. Being “normal” and unattractive is a hit to the perception of “alpha” while being “normal” and attractive is perceived as more alpha than the rich playboy or the antisocial “bad boy.”

For short-term mating desire the largest difference was between groups. In other words, short-term mating desire is driven primarily by physical attractiveness.

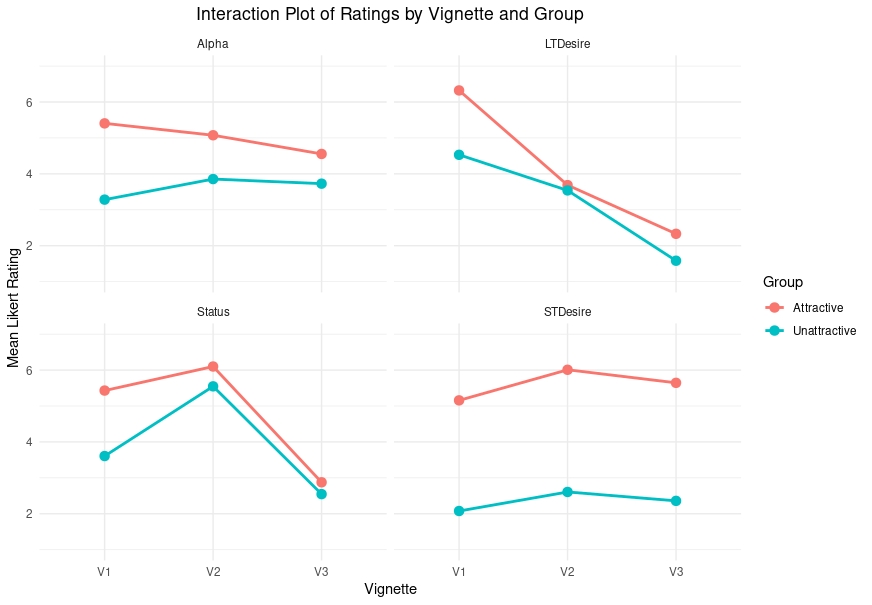

Image 2 shows differences by group for attractiveness ratings across vignettes and alpha ratings across vignettes. Here you can visualize how the difference between attractive and unattractive conditions had a larger effect upon being perceived as “alpha” than the vignette descriptions of behaviors within conditions.

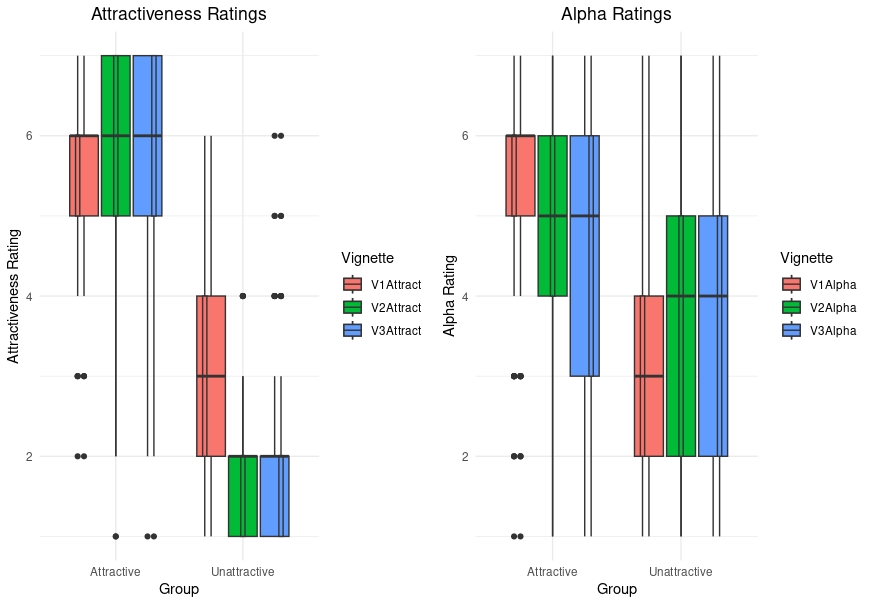

Image 3 shows a split of interaction plots by sex. The patterns are similar for men and women. Men tended to underestimate the negative effect of antisocial behavior relative to women. Women rated the prosocial vignette as higher in status than men did, particularly in the attractive condition.

Women also rated the antisocial vignette lowest in short-term mating desire while men rated the prosocial vignette lowest in short-term mating desire. Being prosocial made unattractive men seem less “alpha” to other men. For women, “alpha” ratings did not differ across vignettes for unattractive men and the prosocial vignette was more “alpha” when the man was physically attractive.

Statistical Tests

A two-way ANOVA was performed on condition (attractive and unattractive) and the three vignette (prosocial, rich, and antisocial) “alpha” ratings. Condition had a main effect (F(1,708) = 126.02, p <.001), the main effect of vignette was not significant (F(2,708) = 2.41, p = .091), and the interaction of group and vignette was significant (F(2,708) = 9.60, p <.001).

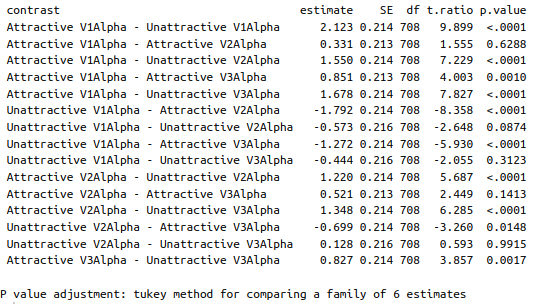

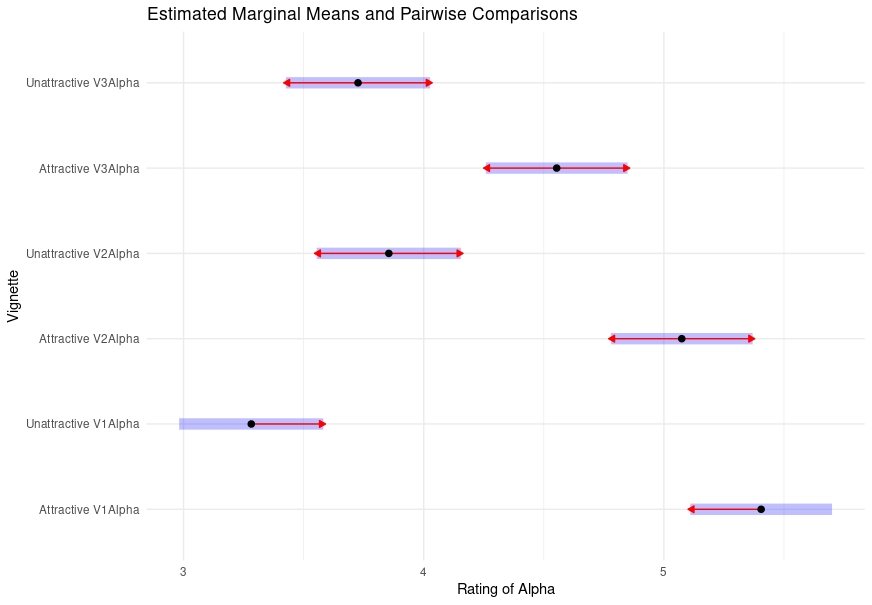

Table 2 below shows pairwise comparisons with Tueky post-hoc corrections pulled from R. Image 4 shows a plot of the estimated marginal means and comparisons. You can puzzle through these if you want to see which vignette-group interactions are significant.

(To interpret the plot, if the arrow from one group overlaps with the arrow from another group then the difference between those two groups is not significant.)

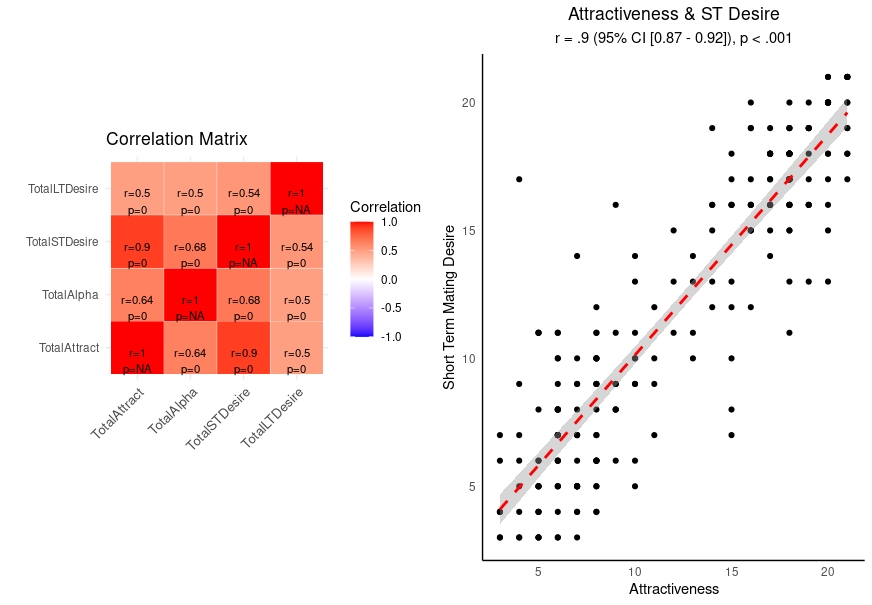

Image 5 shows a correlation matrix of ratings across the two conditions and four variables and a scatterplot showing the relationship between attractiveness ratings and short-term mating desire. All of the correlations are significant and moderate-large in size. The relationship between attractiveness and short-term mating desire is especially high at r = .9.

Questionnaire Traits of Alphaness

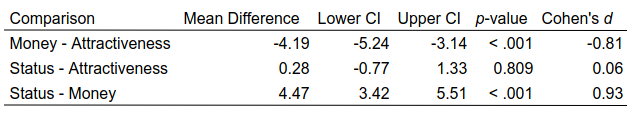

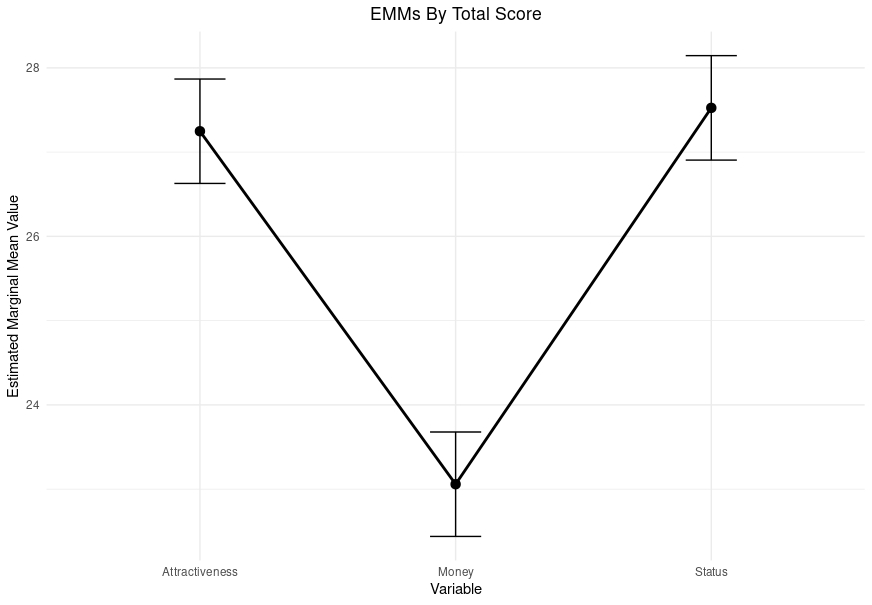

Table 3 and Image 6 show questionnaire results on items representing physical attractiveness, money, and status.

A one-way ANOVA produced a significant effect (F(2, 711) = 62.86, p <.001). A Tukey post-hoc test for comparisons found that the total score of money-related items was significantly different from the total sum of attractiveness-related items (95% CI [-5.24, -3.14], p < .001) and that money-related items were significantly different from status total scores (95% CI [3.42, 5.51], p < .001). Status and attractiveness total scores were not significantly different (95% CI [-0.77, 1.33], p = .809).

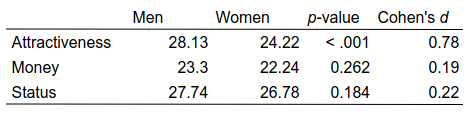

Sex Differences in Questionnaire Scores

T-tests revealed a significant difference in assessing items of physical attractiveness as “alpha” (t(74.14) = 4.79, p < .001., 95% CI [2.29, 5.54]). There was no significant sex difference for ratings of money items (t(73.59) = 1.13, p = .262, 95% CI [-0.81, 5.54]) or status items (t(76.71) = 1.34, p = .184, 95% CI [-0.47, 2.40]) as to how “alpha” they were. Table 4 shows results split by sex.

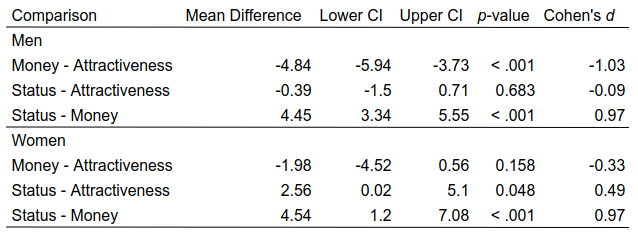

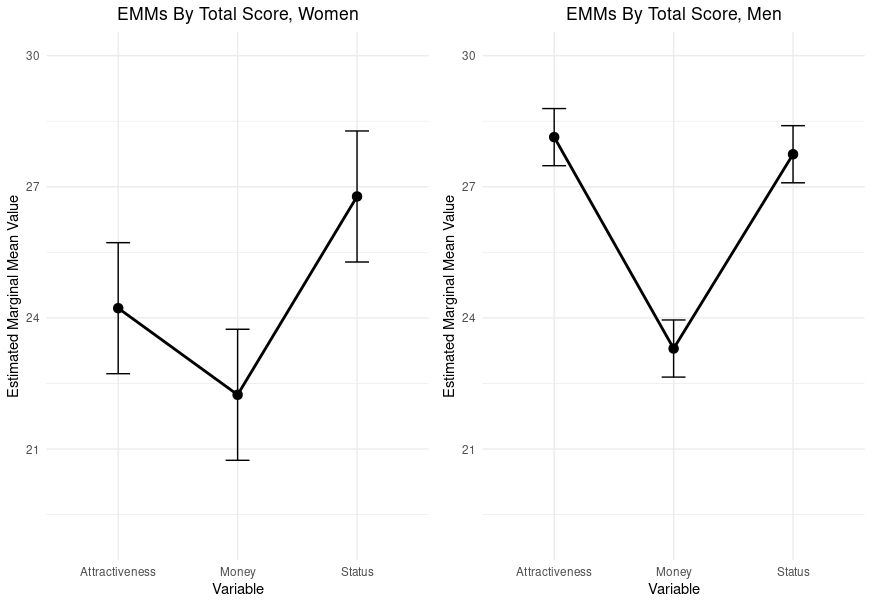

ANOVAs revealed a significant effect for men (F(2, 159) = 8.98, p < .001) and for women (F(2, 549) = 65.18, p < .001). Table 5 shows post-hoc comparisons for men and women and Image 6 shows means for men and women.

Qualitative Results

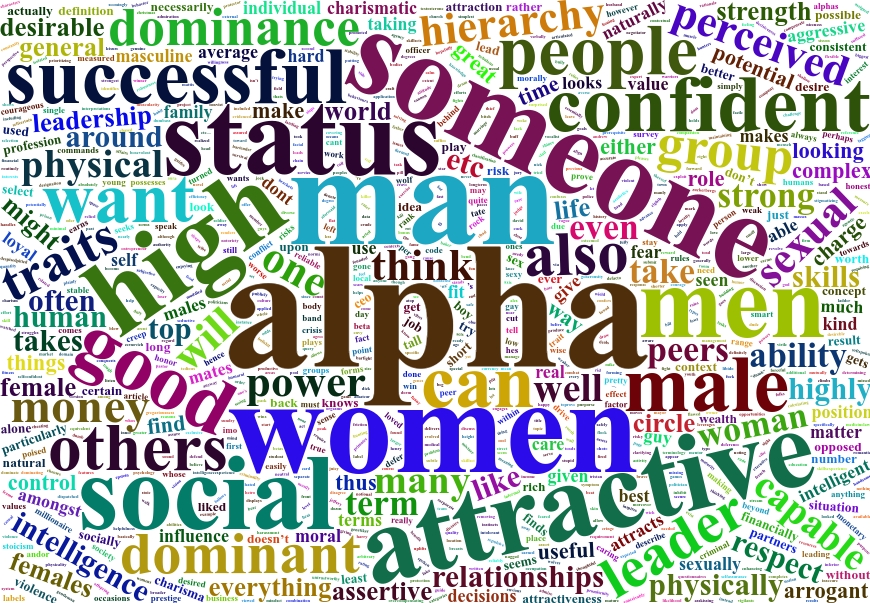

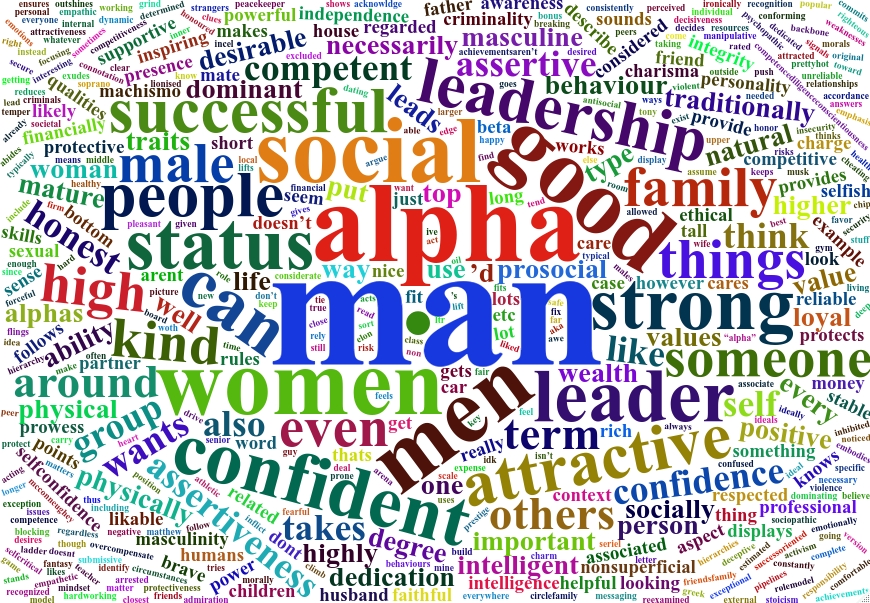

Images 8 (left, men) and 9 (right, women) show word clouds from open-ended participant responses. Image 10 shows a sentiment analysis of themes split by sex.

Discussion

Experimental Results

A few things emerged:

- Vignettes with attractive photos (Condition A) received higher scores across all characteristics, except for being a “beta,” in which case vignettes with unattractive photos (Condition B) were higher.

- Antisocial vignettes received substantially lower ratings on status than prosocial and rich vignettes.

- This effect was more pronounced for female ratings; men underestimated the negative effect of antisocial behavior.

- For vignettes paired with attractive photos, the middle-class prosocial vignette was not much lower than the rich vignette. However, for vignettes paired with unattractive photos, prosocial and antisocial vignettes were substantially lower in status than the rich vignette.

- This did not hold true for women, who did not rate the prosocial unattractive vignette as less “alpha.” Additionally, women rated the prosocial attractive vignette as more “alpha.”

- The prosocial vignette was more desirable as a long-term mate in both conditions.

- The prosocial vignette was perceived as more attractive when paired with an unattractive male photo than rich and antisocial vignettes were when paired with unattractive male photos.

Questionnaire Results

Money was seen as significantly less important insofar as being “alpha” to both men and women. Attractiveness and status were similarly associated with being “alpha” across the whole group. Women placed attractiveness lower than men did, with only status signifiers being significantly more “alpha.”

Qualitative Results

I didn’t dig too much into these yet, but a quick glance at the word cloud and sentiment analysis indicates most participants of both sexes described an “alpha” in positive, prosocial ways. Men used the word “attractive” to describe “alphas” more, consistent with questionnaire results where men rated physically attractive attributes as more “alpha” than women did.

Final Thoughts

Physical attractiveness explained most of the difference across the two conditions for ratings of “alpha.” The effect of the condition had a large effect size (η² = 0.151), while vignette (η² = 0.007) and the condition-vignette interaction (η² = 0.026) were quite small.

Antisocial behavior also produced a pretty big hit to ratings, particularly for ratings given by women. This was largest for ratings of status and long-term mating desire, but this also occurred even for short-term mating desire and even for “alphaness” in the attractive vignette.

The quite large effect produced by the attractiveness manipulation in the experimental condition didn’t fit with the results from the questionnaire, where attractiveness was on par with status (for men) or lower than status (for women). We probably underestimate the extent to which being perceived as “alpha” is merely being conventionally attractive. The experimental manipulation allowed some “revealed” preferences to show though that may not have been captured in the questionnaire.

Men may misperceive the extent to which an antisocial behavior is “alpha” to women: consider that the attractive man when antisocial was not rated significantly differently from the unattractive man! The antisocial man was also perceived as having the lowest short-term mating desirability within the attractive condition for women.

Summed up across all of the results: physical attractiveness is most important for being perceived as “alpha” and is most closely associated with short-term mating desire. Prosocial behavior tends to produce higher perceptions of being “alpha” to women or has null effects, but produces lower perceptions of being “alpha” to other men when the target man is unattractive. Antisocial behavior lowers perceptions of “alphaness,” desirability, and status to women even when the target is attractive.

It doesn’t hurt to be good; it often hurts to be bad. Except, perhaps, in some cases where men are signaling to other men.

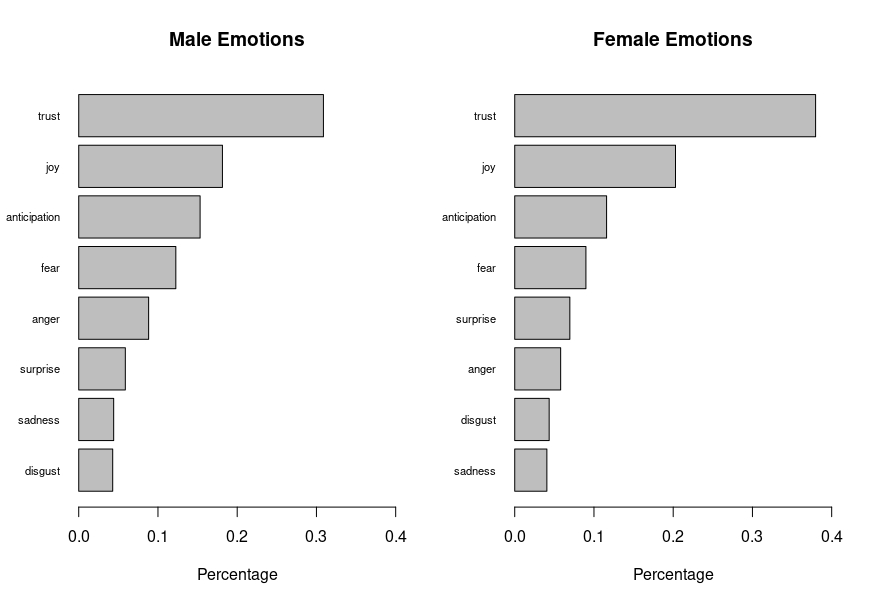

This may explain some of the “ugly alpha” phenomenon we see in the manosphere (see: How Attractive Are Red Pill Influencers? for attractiveness ratings of manosphere influencers from a large sample). Men who are perceived as highly unattractive to women nonetheless cultivate large, predominately male fanbases through showcasing antisocial behavior. See Andrew Tate:

Important Limitations

Limitations sections usually read like filler, where researchers report the obvious. However, I have an important one that I want to make clear because I don’t want these results to be too much of a doomer infohazard:

The photos that appeared in the attractive condition were male models, while the photos that appeared in the unattractive condition were men who were of less than average attractiveness (they were also bald and overweight). The experimental manipulation was effective, but maybe a little too effective. We aren’t considering average men.

Still, the behavior described within vignettes shifted perceptions within groups substantially in some cases, so you should not conclude that behavior does not matter at all. We might also avoid drawing conclusions about interaction effects for men who were more middle-range in physical attractiveness. The results show how physical attractiveness contributes to perceptions of who is “alpha,” but don’t take it as the final word. This is the first empirical investigation into this nebulous construct that I am aware of, but different methods may produce different results in the future.