Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

In 1964, when hearing a US Supreme Court case on obscenity and hardcore pornography, Justice Potter Stewart famously said, “I know it when I see it.” Indeed, we are able to make observations and categorizations without being able to clearly define the parameters (“what is a chair?”). If someone were to tell you that such a thing did not exist, or that you did not know what it was because you couldn’t define it, they would effectively be gaslighting you.

The term “woke” is this way; a word with a common and shared understanding, but that people might have a hard time putting a singular definition upon. Is the inability to define “woke” an indication that people can’t spot it or don’t know what it means? No — we observe patterns and categorize them even without being able to elucidate in a single phrase what exactly is going on. We have a shared understanding of what is “woke.” If we didn’t then we wouldn’t be able to use the term to communicate with at all.

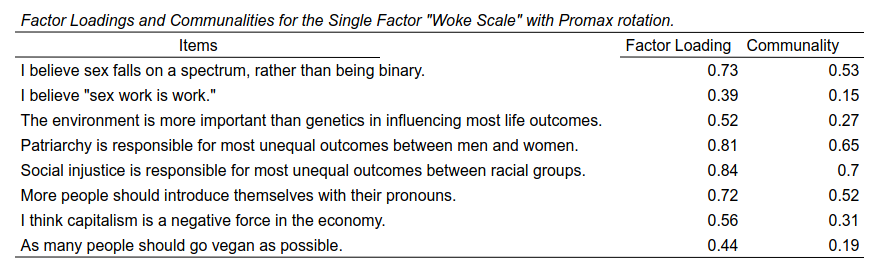

We previously designed and validated the Woke Scale. The way we did this was simply by brainstorming common beliefs associated with the “woke” — essentially how any scale is born. We could have gotten it very wrong, of course, and misunderstood what “woke” was at all. However, the scale did good with the factor analysis. Further, the scale was able to discriminate between participants who called themselves “woke” from participants who did not. We saw a huge difference with a Cohen’s d effect size of 2.04. People who call themselves “woke” score significantly higher on the Woke Scale (by a lot).

Still, the “Woke Scale” made it onto “woke” Twitter/X and received the expected critiques. Among the verbal refuse that was little more than an outraged “how dare you ask that” were a handful of fair ones that boiled down to:

- The scale does not measure “woke,” but something else.

- (It lacks face validity and construct validity.)

- The scale does not predict “anti-Black racism.”

- The scale suffers from social desirability bias.

To us, the scale’s ability to distinguish between people who self-identify as “woke” — as well as the nature of the questions — fulfill the criteria for face and construct validity. However, we can examine this further. An additional step we did not do was to ask participants if they perceived the items as woke. If most people perceive the items on the scale as woke then we have additional evidence for its face validity.

Methods & Results

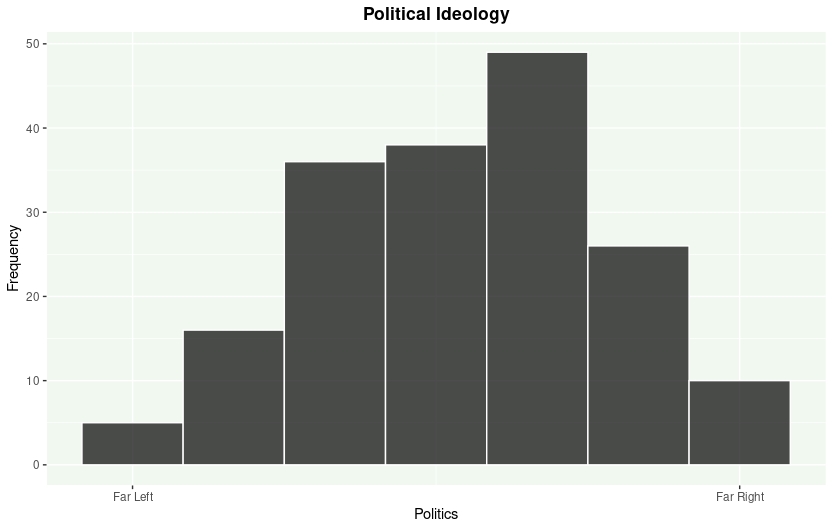

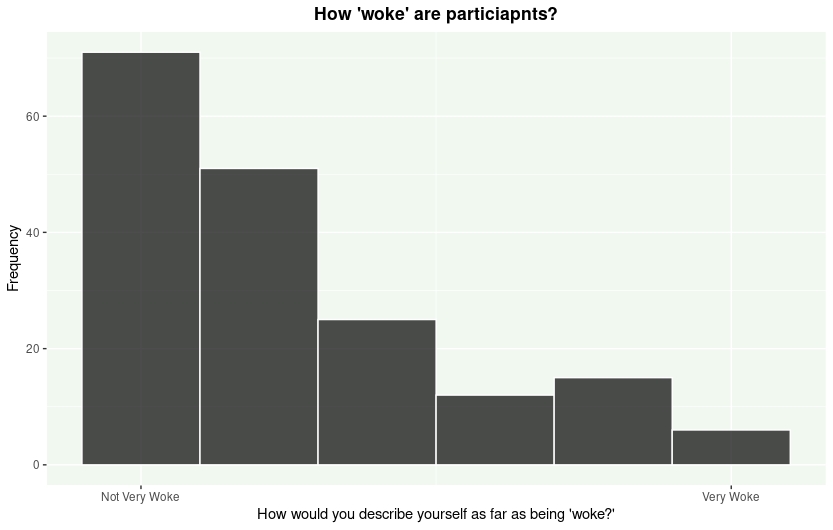

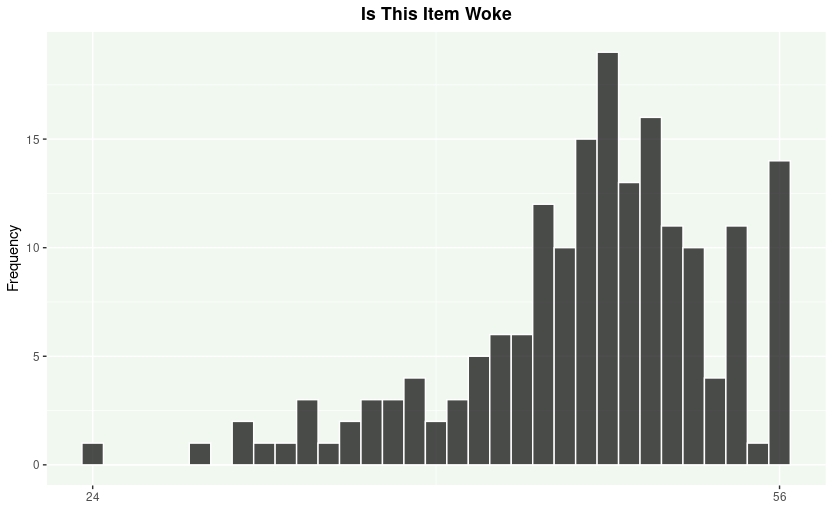

We collected a new sample (N = 180, 81.7% Male) to test the face validity of the Woke Scale. In other words, do people see the items on the scale as “woke?” 31.7% of the participants identified as left wing, 21.1% as centrist, and 47.2% as right wing. 91.1% of participants indicated that they believed they knew what “woke” meant. 88.9% viewed “woke” negatively and 11.7% reported that they were “woke.” Below are descriptive charts:

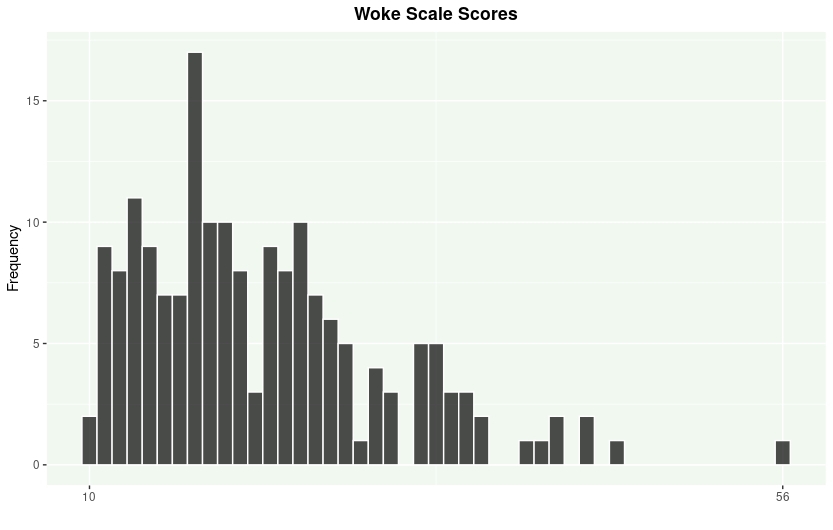

Despite the relatively even distribution of political ideology, most participants scored low on the Woke Scale. Additionally, most participants perceived being “woke” negatively. Most importantly, to ensure we were measuring the construct we believed we were (“wokeness”), most participants perceived most items on the Woke Scale as being “woke.” We can tick off the first objection: most people do see this scale as measuring “wokeness.”

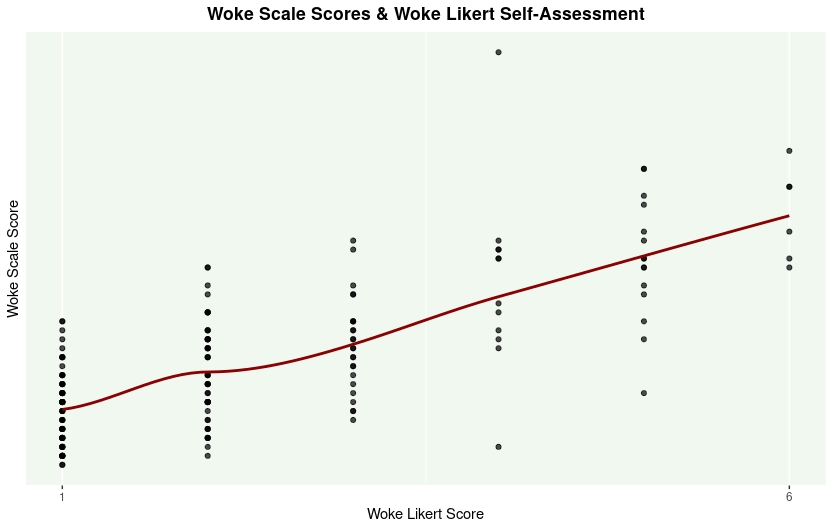

Political ideology correlated with wokeness (r = -.69, p < .001). Additionally, the Likert self-assessment (“How would you describe yourself as far as being “woke?”) predicted scores on the Woke Scale (r = .69, p < .001). The more “woke” participants rated themselves, the higher they scored on the Woke Scale.

Woke Scale scores predicted outcomes on two measurements of racism: the Anti-Black Scale (Katz & Hass, 1988) (r = -.57, p < .001 ) and the Perceptions of Anti-Black Racism scale (Allen, 2020) (r = .67, p < .001). We can tick off the second objection: the scale does predict “anti-Black racism,” at least as measured by these scales.

Finally, there was no relationship between Woke Scale scores and social desirability bias as assessed by the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding Short Form (BIDR-16) (Hart et al., 2015) (r = -.09, p = .199). Additionally there was no significant relationship between social desirability bias and the scores on the two racism measures. It probably shouldn’t surprise you that social desirability bias isn’t driving scores on the Woke Scale, given the generally negative perceptions of “wokeness,” but we can tick off the third objection as well.

Discussion

What is construct validity? This describes the extent to which your scale measures what it is intended to measure. For example, does a scale for “wokeness” measure being “woke.”

What is face validity? This describes the extent to which your scale appears to measure what it is intended to measure. The questions look like they would measure the construct of interest.

This is important: face validity is a low criterion for validity and scales can have good construct validity with little face validity. In other words, a given test may measure something even if it doesn’t seem like it might. This means that you can’t look at a scale and say “it doesn’t measure that” merely by having the subjective feeling that the questions seem unrelated to the construct at hand.

Cronbach & Meehl (1955) described the procedures for ascertaining construct validity. First among them is group discrimination and second is factor analysis. We have seen that the Woke Scale is able to discriminate between groups and that the factor analysis shows the items measure the same underlying construct. The current results show that the Woke Scale also has face validity: most people perceive the items on it as “woke.” We also see that the scale has predictive validity; if “wokeness” is awareness of “anti-Black racism” the Woke Scale is highly correlated with measurements of this (even if the items on the scale do not directly ask about this).

Ultimately it’s a good scale by all of the standard criteria.

References

Allen, A. (2020). On Being Woke and Knowing Injustice: Scale Development and Psychological and Political Implications.

Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological bulletin, 52(4), 281.

Hart, C. M., Ritchie, T. D., Hepper, E. G., & Gebauer, J. E. (2015). The balanced inventory of desirable responding short form (BIDR-16). Sage Open, 5(4), 2158244015621113.

Katz‚ I.‚ & Hass‚ R. G. (1988). Racial ambivalence and American value conflict: Correlational and priming studies of dual cognitive structures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology‚ 55‚ 893-905.