Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

Sex differences in sexual and emotional jealousy — men showing relatively more sexual jealousy and women showing relatively more emotional jealousy — are robust and well-replicated in the psychological literature.

Scelza et al. (2020) replicated sex differences in jealousy across eleven cultures, finding greater male sexual jealousy in a forced-choice task between sexual and emotional jealousy. However, there was considerable variation between cultures, with populations that were more monogamous and more invested in parenthood expressing more jealousy. In a large Brazilian sample, Valentova et al. (2020) found women expressed higher emotional jealousy than men. However, there was no sex difference for non-heterosexual participants nor participants in CNM (consensually non-monogamous) relationships. In a demographically representative sample from Australia (de Visser et al., 2019), similar sex differences were observed with men expressing more sexual and women expressing more emotional jealousy.

Sex differences in jealousy begin in adolescence; Larsen et al. (2021) found that adolescent men (age 16-19) expressed more sexual jealousy than women. Additionally, sexual orientation can interact with jealousy as well. In samples from Brazil, Portugal, and Chile, bisexual women were more jealous about sexual infidelity with an opposite-sex rival (Valentova et al., 2022). Sex differences in jealousy are also not exclusive to romantic relationships. Krems et al. (2022) found a sex difference in the context of friendship jealousy. Female participants experienced greater jealousy within the context of losing a best friend to another.

Traits of romantic rivals may also influence expressions of jealousy. Dunn and Ward (2020) found that men expressed higher jealousy to sexual Snapchat messages while women expressed higher jealousy to emotional Snapchat messages. Additionally, men expressed higher jealousy when the Snapchat message was from a stranger rather than a brother, while women expressed higher jealousy when the Snapchat message was from a sister rather than a stranger. Pollet and Saxton (2020) replicated effects for rival attractiveness in women and similarly found effects of rival attractiveness for women in a subsequent meta-analysis. For men, both rival attractiveness and rival dominance elicited higher jealousy. Nascimento & Little (2020) similarly found that attractive and seductive rivals elicited higher jealousy and the effect was stronger for women, with women being willing to engage in more mate-retention strategies in response.

Why do we see sex differences in jealousy? Men may experience more sexual jealousy both because it represents a threat to paternal certainty and a threat to paternal opportunity (Edlund et al., 2019). Conversely, women may experience more emotional jealousy because it represents a threat to commitment and parental investment in a long-term pair bond.

Although we see a sex difference in jealousy, it’s important to understand that this does not imply men don’t experience emotional jealousy nor that women don’t experience sexual jealousy. Across the research, men and women both express high jealousy on items that you would expect to induce high jealousy. What we see are relative differences; not the absence of emotional or sexual jealousy in women or men respectively.

Much of the research on sex differences in jealousy uses forced-choice methodology (participants are forced to pick between an emotional or sexual vignette and indicate which of the two would induce more jealousy). Additionally, jealousy-inducing scenarios presented in the research are often clear and unambiguous (depicting clearly sexual acts, affairs, or infidelity).

However, real-world jealousy often occurs over ambiguous events and behaviors. People get jealous over trivial events; anything and nothing at all. These don’t fall clearly into sexual or emotional infidelity (and may not be acts of infidelity or threats from rivals at all). This raises the question: do we see sex differences in jealousy within the context of ambiguous scenarios that are neither emotional nor sexual?

Methods

371 participants (33% female) were collected from a social media convenience / snowball sample. 86.1% of the sample was heterosexual, 11.3% was bisexual, and 2.7% was gay or lesbian. 85% of the sample identified as monogamous, 7.2% were polyamorous, and 7.8% said they did not know or were unsure. 51.7% were in a committed relationship and the remainder indicated that they were not.

Participants rated 24 short items depicting scenarios where they might feel jealous. Participants were instructed, “When taking this survey, please try to reflect on if the situation described would make you feel jealous even if you feel that it might not be entirely fair or rational to be jealous” and indicated how jealous they would feel on a scale of 1-5. Participants in committed relationships were asked to imagine the scenario describing their current partner, while participants not in committed relationships were asked to imagine how it would make them feel. Jealousy items were derived from novel experiences reported to us.

The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale-Short Form (ECR-S) (Wei et al., 2007) was administered to assess anxious and avoidant attachment.

The Relationship Assessment Scale (Hendrick, 1988) was used to assess relationship satisfaction.

Results

Age

A small correlation emerged for age and total jealousy scores (p < .01, r = -.14), with older participants scoring lower in total jealousy than younger participants. Age also had a small correlation with anxious (p < .01, r = -.15), but not avoidant, attachment. For participants in committed relationships, age was inversely correlated with relationship satisfaction (p < .05, r = -.14).

Monogamy and Polyamory

Monogamous participants scored higher in total jealousy (M = 66.3) than polyamorous participants (M = 50.8) (p < .001, d = .66). Monogamous participants also scored higher in anxious attachment (M = 22.3) than polyamorous participants (M = 18.4) (p < .01, d = .54). No significant difference in avoidant attachment emerged for monogamous and polyamorous participants.

Additionally, no difference in relationship satisfaction nor age emerged for monogamous and polyamorous participants.

Committed Relationships

Participants in committed relationships had lower total jealousy scores than participants who were not (p < .01, d = -.29). Participants in committed relationships were also lower in anxious (p < .001, d = -.65) and avoidant (p < .001, d = -.64) attachment.

Sex Differences & Jealousy

Men and women did not differ in total jealousy scores (p > .05, d = -.07). Men and women also did not differ significantly in anxious attachment, avoidant attachment, nor relationship satisfaction.

Jealousy had a small inverse correlation with relationship satisfaction for the total sample (p < .001, r = -.18) and for participants in committed relationships (p < .01, r = -.21). Split by sex, higher jealousy predicted lower relationship satisfaction for men (p < .01, r = -.22), but not for women.

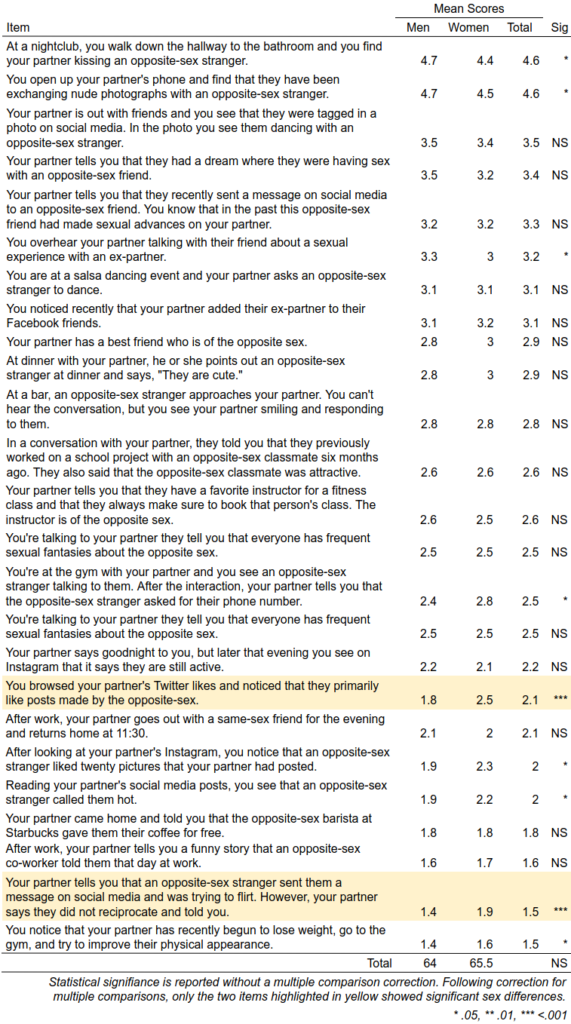

Below are sex differences for individual jealousy items. Statistical significance is reported without a correction for multiple comparisons. With a correction for multiple comparisons, sex differences in jealousy remained for only two items (“You browsed your partner’s Twitter likes and noticed that they primarily like posts made by the opposite-sex” and “Your partner tells you that an opposite-sex stranger sent them a message on social media and was trying to flirt. However, your partner says they did not reciprocate and told you”). These items are highlighted in yellow.

Jealousy items are ordered from the ones with the highest to lowest mean jealousy scores.

Result Summary

- Younger participants scored slightly higher in jealousy and anxious attachment.

- Older participants scored slightly lower in relationship satisfaction.

- Men and women did not differ significantly in relationship satisfaction nor total jealousy. Few sex differences emerged for individual jealousy items, in particular for more ambiguous items.

- Monogamous participants had higher jealousy and higher anxious attachment than polyamorous participants.

- Higher total jealousy was associated with lower relationship satisfaction. However, this relationship existed only for men. Women higher in total jealousy did not have lower relationship satisfaction.

Discussion

Given that the situations provided in the survey don’t have any obvious or deliberate acts of cheating, both male and females reported little to no difference in how they felt jealousy. Ambiguous scenarios perhaps provide more of a gateway into future actions of cheating. These situations may be a precursor to actual events of cheating but perhaps not perceived as a threat yet. One of the larger differences found in our survey was pertaining to liking posts from the opposite sex. Women reported being more jealous in this case perhaps indicating threat to an emotional connection versus sexual. Men reported higher jealousy when the question pertained to physical touch or messages containing nude photographs being exchanged. More ambiguous questions such as going out late with friends or working with someone of the opposite sex they found attractive had pretty equal outcomes in terms of jealous feelings.

Our data shows that the younger generation showed more jealousy in these scenarios than older people. Polyamorous people showed low jealousy across the board, which makes sense due to monogamous couples reporting significantly higher jealousy.

Although the sex difference in emotional and sexual jealousy is well-established, further research might explore sex differences in ambiguous or novel contexts. The events that evoke jealousy on a day-to-day basis are not always neatly grouped into perceived emotional or sexual threats.

References

De Visser, R., Richters, J., Rissel, C., Grulich, A., Simpson, J., Rodrigues, D., & Lopes, D. (2019). Romantic jealousy: A test of social cognitive and evolutionary models in a population-representative sample of adults. The Journal of Sex Research.

Dunn, M. J., & Ward, K. (2020). Infidelity-revealing Snapchat messages arouse different levels of jealousy depending on sex, type of message and identity of the opposite sex rival. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 6(1), 38-46.

Edlund, J. E., Buller, D. J., Sagarin, B. J., Heider, J. D., Scherer, C. R., Farc, M. M., & Ojedokun, O. (2019). Male sexual jealousy: Lost paternity opportunities?. Psychological reports, 122(2), 575-592.

Hendrick, S. S. (1988). A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 93–98.

Krems, J. A., Williams, K. E., Merrie, L. A., Kenrick, D. T., & Aktipis, A. (2022). Sex (similarities and) differences in friendship jealousy. Evolution and Human Behavior, 43(2), 97-106.

Larsen, P. H. H., Bendixen, M., Grøntvedt, T. V., Kessler, A. M., & Kennair, L. E. O. (2021). Investigating the emergence of sex differences in jealousy responses in a large community sample from an evolutionary perspective. Scientific reports, 11(1), 6485.

Nascimento, B. S., & Little, A. (2020). Mate retention behaviours and jealousy in hypothetical mate-poaching situations: Measuring the effects of sex, context, and rivals’ attributes. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 6(1), 20-29.

Pollet, T. V., & Saxton, T. K. (2020). Jealousy as a function of rival characteristics: Two large replication studies and meta-analyses support gender differences in reactions to rival attractiveness but not dominance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(10), 1428-1443.

Scelza, B. A., Prall, S. P., Blumenfield, T., Crittenden, A. N., Gurven, M., Kline, M., … & McElreath, R. (2020). Patterns of paternal investment predict cross-cultural variation in jealous response. Nature human behaviour, 4(1), 20-26.

Valentova, J. V., de Moraes, A. C., & Varella, M. A. C. (2020). Gender, sexual orientation and type of relationship influence individual differences in jealousy: A large Brazilian sample. Personality and individual differences, 157, 109805.

Valentova, J. V., Fernandez, A. M., Pereira, M., & Varella, M. A. C. (2022). Jealousy is influenced by sex of the individual, their partner, and their rival. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(6), 2867-2877.

Wei, M., Russell, D. W., Mallinckrodt, B., & Vogel, D. L. (2007). The experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR)-Short Form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88, 187-204.