Enjoy DatePsychology? Consider subscribing at Patreon to support the project.

A popular cultural belief is that beauty is subjective; even that beauty itself is a myth (Wolf, 2013). It is, frankly, bullshit. Research on attractiveness within the fields of psychology and neuroscience consistently show that human beings have some degree of shared beauty recognition across cultures. Infants recognize physical beauty at only two months old (Langlois et al, 1991; Ramsey et al., 2004; Rubenstein et al., 1999). Neuroscientific research shows that we process beauty before we are consciously aware of it, that we recognize beauty as we recognize faces, and that beauty is rewarding (for a full review see: The Neuroscience of Facial Attractiveness).

Further, the entire field of plastic surgery and the whole beauty industry is predicated on the fact that certain aesthetic modifications are able to make you more beautiful to more people.

If beauty were randomly perceived (and this tends to be what people mean when they say beauty is subjective) this would not be possible at all.

Beauty is not merely “in the eye of the beholder” nor is it entirely shaped by cultural convention (Etcoff, 1994). In some cases, traits that signal health and low mutational load are associated with beauty (e.g. facial symmetry or averageness). In others, traits that signal fertility are associated with beauty (the hip-to-waist ratio). Traits that might provide an advantage in the domain of natural selection may also come to be perceived as beautiful (height or muscularity in men). Finally, traits may be selected for simply because they are beautiful — sexual selection — and preferences for those traits will persist in future generations (because, yes, aesthetic preferences are heritable: see Bronstad & Russell, 2007; Germane et al., 2015).

We therefore know that beauty reflects objective physical traits. This is how attractiveness should be understood: as a subjective consensus on objective physical traits (see: Can Women Identify An Average Face?). Further, we also know men agree more on female attractiveness than women agree on male attractiveness (Hönekopp, J., 2006; Langolis et al., 2000: Roth et al., 2003).

This should make a blueprint for enhancing female attractiveness more clear. Men are more consistent in their physical mate preferences.

Mate Preferences and Masculine-Feminine Polarity

Femininity is robustly associated with male perceptions of attractiveness in women, however the relationship between masculinity and attractiveness in men is less clear (Kleisner et al., 2023; O’Connor et al., 2013). Cues of femininity may signal benefits (e.g. fertility, youth, or health) (Buggio et al., 2012) with few trade-offs, while cues of masculinity may represent more trade-offs (e.g. physical size in a man may represent both a potential threat to a mate and the ability to protect a mate from outside threats). Given this, strategies to enhance physical attractiveness in women are essentially strategies to enhance physical cues of femininity. For example, facial rejuvenation surgery is effective in enhancing perceptions of female attractiveness and femininity (Reilly et al., 2015).

Voice pitch is correlated with subjective assessments of femininity as well as externally-rated facial femininity (Feinberg et al., 2005). Vukovic et al. (2008; 2010) found that women with higher pitched voices also expressed stronger preferences for deeper male voices. Women higher in physical attractiveness also show stronger preferences for masculine men both in subjective (Little et al., 2001) and objective measurements (Penton-Voak et al., 2003). Holzleitner & Perrett (2017) found a number of individual differences in preferences for masculinity. Women who had a stronger heterosexual orientation, who were physically healthier, and who perceived themselves as more attractive indicated a stronger preference for facial masculinity in men.

In popular dating discourse the notion of “masculine-feminine polarity” is en vogue. Indeed, much of our folk psychology turns out to be true (humans are good pattern recognizers, although sometimes we see patterns where there are none). That masculine men show a preference for feminine women — and vice versa — has some empirical support behind it.

Popular Culture Is Right About Beauty

From Disney princesses to beauty pageants women are bombarded with what is deemed beautiful. This begins as early as children start to dabble with pretend makeup and costumes. Beauty expectations are ever-present and begin early on for young girls. An early encounter with beauty standards comes through one’s first encounter with Barbie: she has an ‘ideal’ figure, beautiful makeup, perfect hair, and more.

Rice et al. (2016) found that exposure to Barbie in a cohort of girls aged 5-8 produced an acute effect of internalizing an ideal beauty standard based on the doll. Although this had no effect on self-esteem and body image, it is clear that early exposure to beauty shapes perceptions of what is ideally beautiful. What long-term impacts this may have are unknown, it may still represent an effort to feed young girls the belief that beauty is the ultimate goal for opportunities in careers, finding a mate, and gaining self-confidence. Indeed, women who perceive themselves as more beautiful do have more self confidence (Mazur, 1986).

Although beauty has some cultural and generational variability, one thing that remains stable is the effect of youth. Plastic surgery is more popular than ever and acceptance that you can become beautiful through cosmetic surgery is normalized. Cosmetic surgery also does what it promises: in most cases it works. For example, Asimakopoulou et al. (2019) found that women report being very happy with their breast augmentations and that breast augmentation produced higher self-confidence for the women who underwent the procedure.

Exploiting the desire to be beautiful and flawless remains the bread and butter of cosmetic clinics and brings in billions of dollars annually. Women continue to feel pressure to meet these expectations; this effect is amplified through social media. Sari et al. (2022) highlight how we perceive beauty, how beauty is constructed, and also how beauty and body care is identified through the lens of social media. Through six years of research, they also found how beauty trends with social media and social standards has caused women to be dissatisfied and how that is projected through body image amplified through social media and primarily Instagram.

Scrolling an endless pool of flawless and filtered women creates an unrealistic standard and produces negative impact through upward social comparisons. Van De Ven (2015) found envy and admiration both develop through motivation to improve one’s self through social influences. These trends are fleeting and may produce an exhausting chase to keep up with new procedures. However, novel and trendy procedures may exceed and overshoot what is needed to attract a mate (or what is really desired by men). The traits that men find desirable are often related to reproduction and health; symmetrical faces, a good hip-to-waist ratio, breast size, and normal-range BMI (Buggio et al., 2012; Henriquez & Patnaik, 2020). What is feminine may have some subjective element, but perceptions of what is feminine correlate with traits perceived as attractive, and these tend to be traits that predict “good genes” and reproductive ability. Attraction to these is driven by our biology.

The preferences for women who are fit, in some cases with larger breasts and smaller waists, may remain stable as they signal reproductive capacity. Conversely, current trends such as the Brazilian butt lift could be a product of an ever-changing beauty standard. These may be pushed more by the beauty industry than a real desire for enormous buttocks, and we may find them phased out as the trend recedes.

Do cosmetic industries mirror what is attractive to men or do they manifest trends, marketing them to women, when men otherwise would not find the new modifications to be attractive at all? A young and impressionable female consumer base might not be aware of the difference. Indeed, the youngest cohort of women may be especially susceptible to influence from this kind of marketing (Britton, 2012). The unattainable nature of cosmetic trends may be a boon for the cosmetic industry. After all, if you can’t reach your final goal, why not just keep buying cosmetics and surgical procedures until you can? This is perhaps the best business ploy that a company can have.

On the other hand, what if the beauty standards men desire most are attainable? Rather than following the cutting edge of cosmetic and fashion trends, what if what men really desire comes down to a minimal amount of grooming, health, and bodily upkeep? You might get much further losing ten pounds than getting lip filler injections. The extra hour you spend applying makeup might be better spent on the treadmill.

Methods & Results

We collected a social media convenience / snowball sample (N = 533, 73.7% male). The mean age of the sample was 35.5 (SD 11.3). 88.2% of the sample was heterosexual, 11.1% was bisexual, and .75% was gay or lesbian.

Participants were presented with a series of questions that followed the format “The average woman would see an improvement to her attractiveness.” For example, “The average woman would see an improvement to her attractiveness if she had a rhinoplasty procedure” and “The average woman would see an improvement to her attractiveness if she had a Brazilian butt lift.” Men and women rated these items on a 7-point Likert scale from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.”

Participants also self-assessed their own masculinity and femininity on the Traditional Masculinity-Femininity (TMF) scale (Kachel et al., 2016). Past research has found some reliability in self-assessments of masculinity and femininity (Pereira et al., 2019). Participants also indicated their preference for masculinity and femininity in an opposite-sex partner on a 7-point Likert scale (from “Not Very Masculine/Feminine” to “Very Masculine/Feminine”).

Four questions were presented to assess beliefs about motives women have to enhance their beauty.

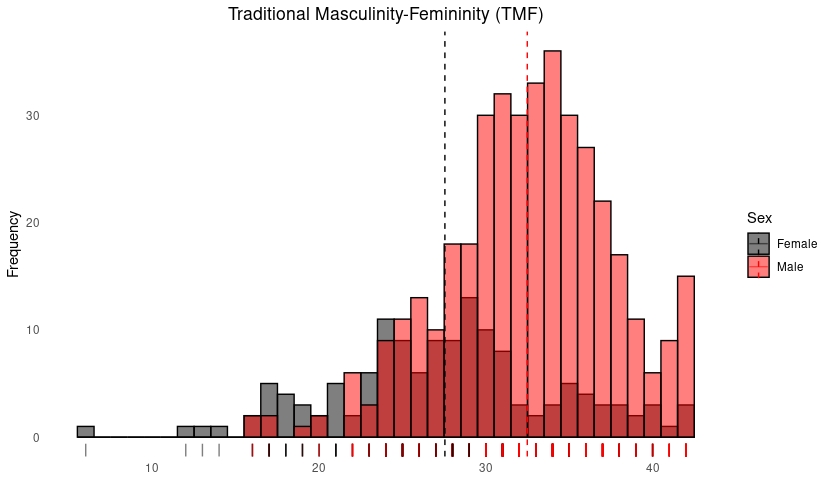

The histogram below (Image 1) shows the distribution of male and female scores on the Traditional Masculinity-Femininity (TMF) scale. Age was positively correlated with masculinity scores for men (r = .13, p < .01), but not for women.

Image 1. Distribution of male and female scores on the Traditional Masculinity-Femininity (TMF) scale. Dark red indicates overlapping female distribution.

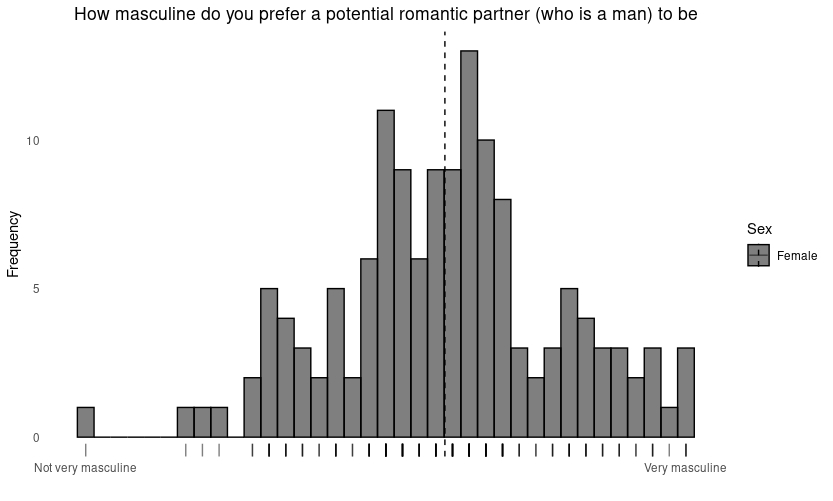

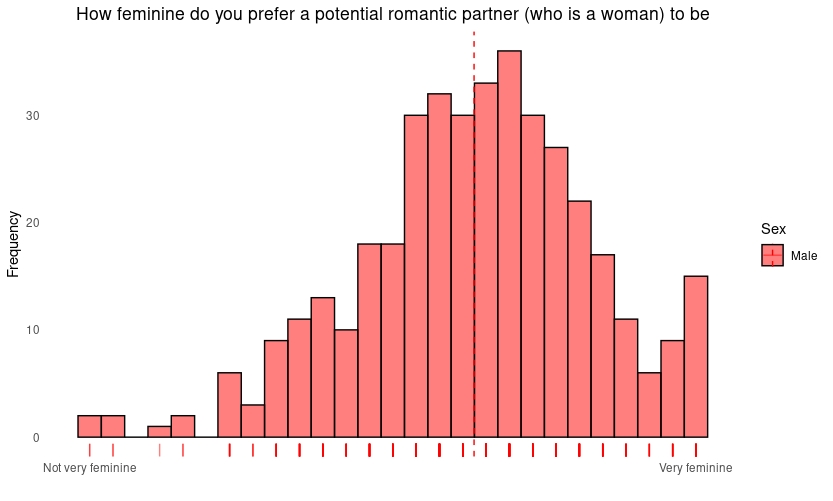

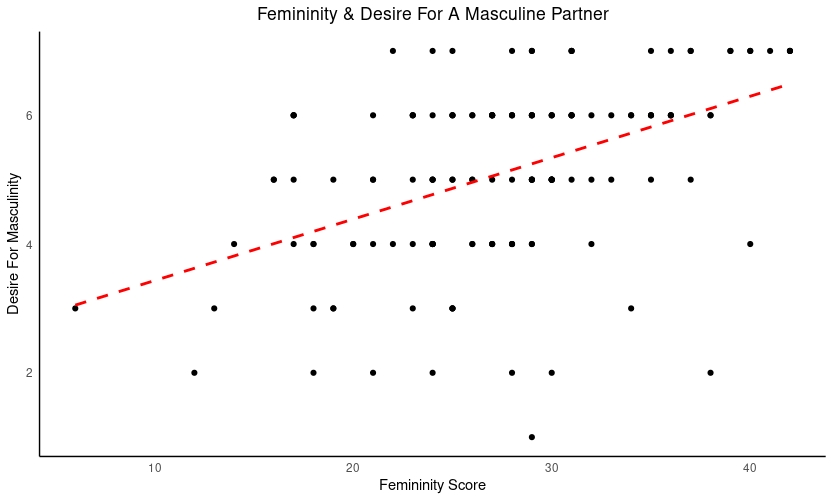

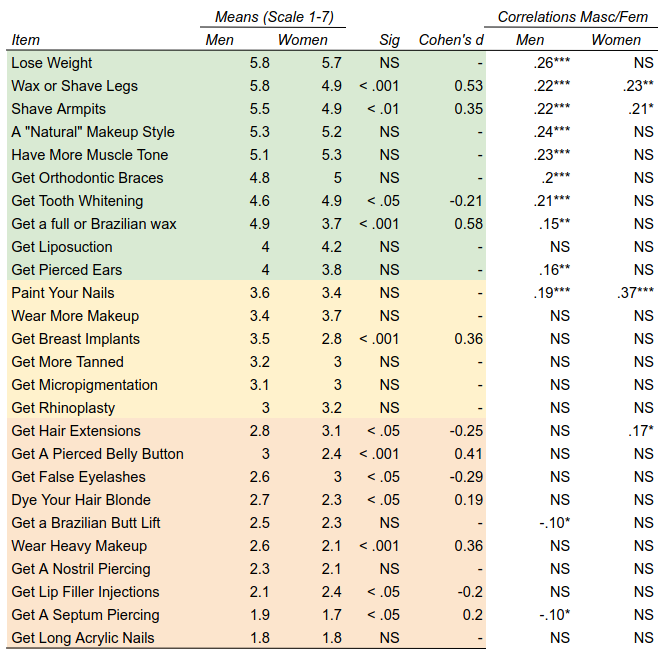

The histograms below (Images 3 & 4) show preferences for masculinity and femininity in opposite sex partners. Age was not correlated with preferences for masculinity or femininity in our sample. Participants who assessed themselves higher in femininity and masculinity on the TMF indicated a stronger preference for more feminine/masculine opposite-sex romantic partners. (men r = .41; women r = .48, all ps < .001) (Images 5 & 6).

Images 3 & 4. Preferences for masculinity and femininity in opposite-sex romantic partners as reported by men and women.

Images 5 & 6. Spearman correlations showing positive associations between self-assessed masculinity/femininity and preferences for masculinity/femininity in opposite-sex romantic partners. Participants who rated themselves as more masculine indicated a higher preference for more feminine romantic partners. Participants who rated themselves as more feminine indicated a higher preference for more masculine romantic partners.

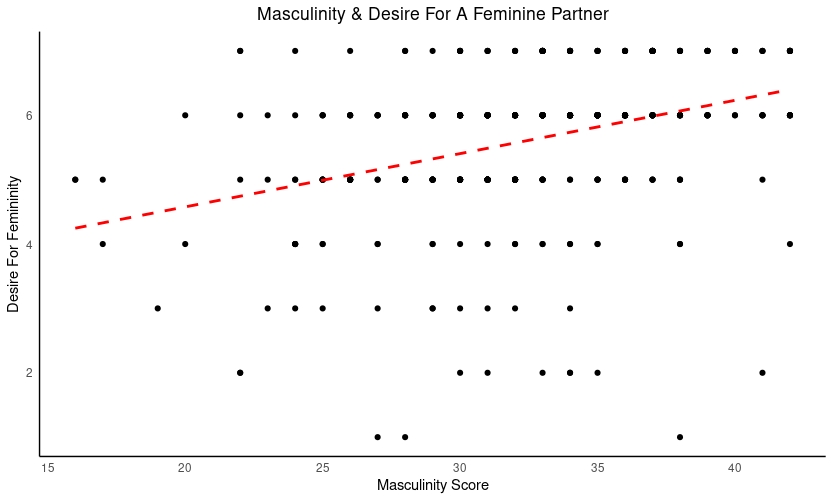

The table below (Table 1) shows mean scores for men and women on beauty enhancement items, significance, Cohen’s d effect sizes, and correlations with self-rated masculinity/femininity on the TMF. Items are ordered from highest (believed to enhance attractiveness the most) to lowest total mean scores.

Although statistically significant sex differences emerged for some items, it’s notable that the order of items was largely the same for men and for women, indicating high agreement between the sexes on what items were most or least likely to improve an average woman’s attractiveness.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for male raters was 0.87 with an average inter-item correlation of 0.2. For female raters, alpha was .91 with an average r of .26. Intclass correlation coefficients for average random raters were .78 for men and .85 for women. These results indicate high agreement across participants on what beauty enhancement techniques are perceived to be more or less effective.

Significant correlations emerged between self-assessed masculinity and preferences for the top 8 beauty-enhancing strategies. Men who perceived themselves as more masculine were more likely to agree that these beauty enhancement techniques would make the average woman more attractive.

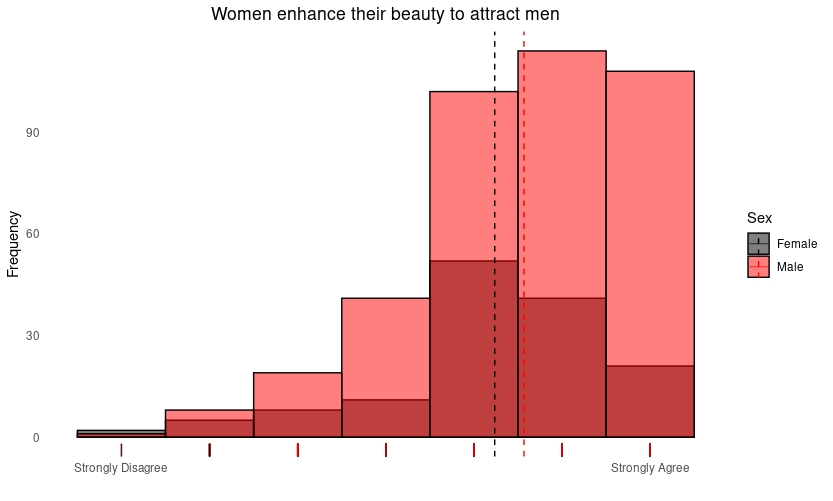

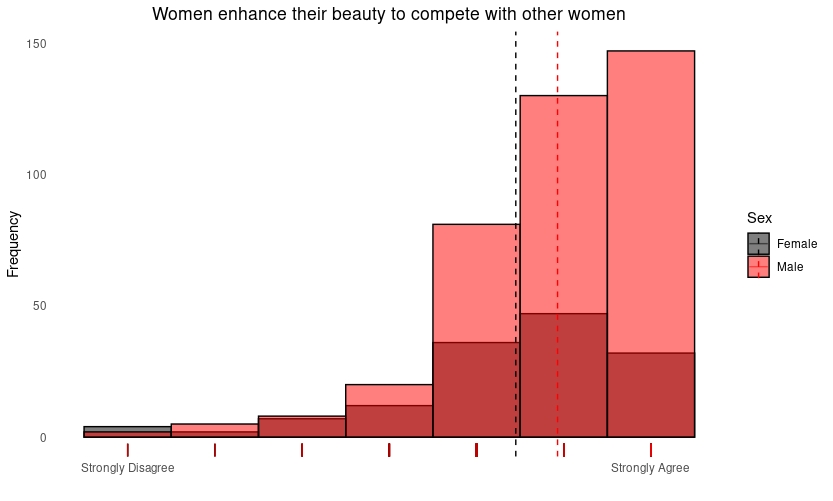

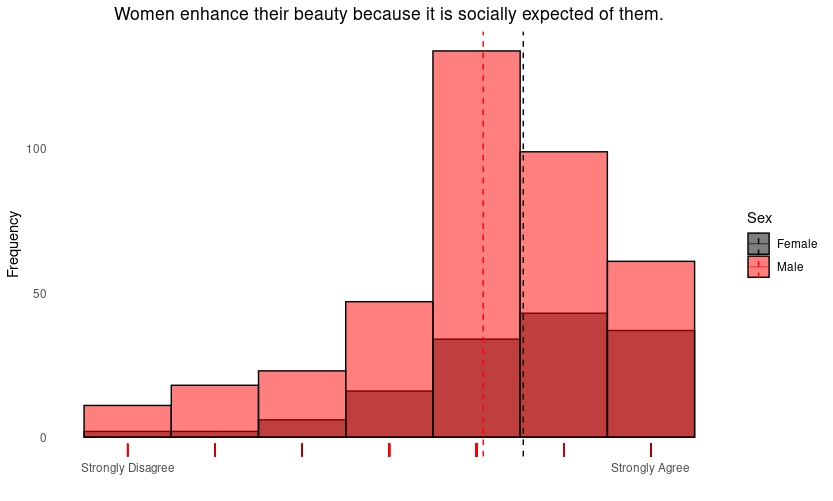

A series of non-parametric Wilcox tests revealed sex differences across the four items assessing perceived motivations for beauty-enhancement strategies. Men were more likely to believe that women enhance their beauty to attract men (p < .01, d = .26) and to compete with other women (p < .001, d = .38). Women were more likely to believe that women enhance their beauty to feel good in their own bodies (p < .001, d -.32) and due to social expectations (p < .001, d = -.33). Although significant sex differences with small-to-moderate effect sizes emerged across all four items, distributions of ratings (Images 7-10) show most participants affirmed positive agreement with all four items regardless of sex.

Images 7-10. Distributions of male and female agreement on female reasons for beauty-enhancing strategies. Men were significantly more likely to believe that women engage in beauty-enhancement strategies to attract men and to compete with other women. Women were significantly more likely to believe that women enhance their beauty to feel good in their own bodies because beauty enhancement is a social expectation. Dotted lines represent mean scores for groups.

Results Summary

- Age was positively associated with self-rated masculinity for men.

- Self-rated masculinity was positively associated with a preference for femininity in opposite-sex romantic partners.

- Self-rated femininity was similarly associated with a preference for masculinity.

- Men and women perceived the effectiveness of female beauty-enhancement strategies similarly and showed high agreement across items.

- Weight loss was the female beauty-enhancement strategy endorsed as the most effective by men and women.

- Some small-medium sized sex differences emerged when assessing perceived motivations for female beauty enhancement.

Discussion

Consistent with past research, our results provided evidence for a “masculine-feminine polarity” effect: more masculine men preferred more feminine women and more feminine women preferred more masculine men. Part of one’s self-concept of masculinity and femininity in an interpersonal context may consist of a heightened preference for typical gender or sex role congruent traits and behaviors in the opposite sex. That is to say, a masculine man may see a feature of his own masculinity as a desire for highly feminine women (and vice versa).

Because femininity is robustly associated with attractiveness in women (and masculinity is occasionally, but not infrequently, associated with attractiveness in men) we may also see that higher levels of masculinity and femininity provide heightened access to more desirable opposite-sex partners. A preference for a more masculine or feminine partner may boil down to a preference for a more attractive partner.

The ranking of beauty-enhancement strategies made by men closely mirrored that made by women. In other words, men and women showed high agreement on what beauty-enhancement strategies would be most effective for the average woman. The top strategy was weight loss. Additionally, the top operative cosmetic procedure was liposuction. Despite “body positivity” trends, “fat acceptance,” “big is beautiful,” and other top-down activist cultural narratives, it remains a fact that overweight and obese bodies are perceived as less attractive than normal-weight and thin bodies.

The top-ranked beauty enhancement strategies endorsed by men and women were also not invasive procedures; they reflected conventional and common grooming practices and beauty-enhancement strategies. These boiled down to waxing, shaving, and fixing one’s teeth. All of the top-endorsed items save for one were also positively correlated with self-rated masculinity in men. The more masculine the men, the more they believed that these beauty-enhancement strategies would increase the physical attractiveness of the average woman.

Contrary to what the data shows in regards to preferences, the beauty industry leads women to believe beauty is attained through makeup and expensive procedures. This is amplified through social media and advertisements. Perhaps their goal is to view beauty as objective and attainable simply through spending more money. This also creates the idea men do not appreciate natural beauty and this narrows the dating pool and opportunities for women.

What do these results mean in a practical sense? If you (as a woman) prefer more masculine men then your best bet is to be a more conventionally feminine woman.

References

Adamson, Peter A. MD, FACS, FRCSC; Doud Galli, Suzanne K. MD, PhD. Modern Concepts of Beauty. Plastic Surgical Nursing 29(1):p 5-9, January 2009. | DOI: 10.1097/01.PSN.0000347717.98155.8d

Asimakopoulou, E., Zavrides, H., & Askitis, T. (2019). The impact of aesthetic plastic surgery on body image, body satisfaction and self-esteem. Acta chirurgiae plasticae, 61(1‐4), 3-9.

Banerjee, Smita (2008). Fact or Wishful Thinking? Biased Expectations in I Think I Look Better When I’m Tanned. American Journal of Health Behavior, 32(3), –. doi:10.5993/ajhb.32.3.2

Britton, Ann Marie, “The Beauty Industry’s Influence on Women in Society” (2012). Honors Theses and Capstones. 86.

https://scholars.unh.edu/honors/86

Bronstad, P. M., & Russell, R. (2007). Beauty is in the ‘we’of the beholder: Greater agreement on facial attractiveness among close relations. Perception, 36(11), 1674-1681.

Buggio, Laura; Vercellini, Paolo; Somigliana, Edgardo; Viganò, Paola; Frattaruolo, Maria Pina; Fedele, Luigi (2012). “You are so beautiful”*: Behind women’s attractiveness towards the biology of reproduction: a narrative review. Gynecological Endocrinology, 28(10), 753–757. doi:10.3109/09513590.2012.662545

Dimitrov, D., & Kroumpouzos, G. (2023). Beauty perception: A historical and contemporary review. Clinics in Dermatology, 41(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2023.02.006

Etcoff, Nancy L. (1994). Beauty and the beholder. , 368(6468), 186–187. doi:10.1038/368186a0

Fallon, April E.; Rozin, Paul (1985). Sex differences in perceptions of desirable body shape.. , 94(1), 102–105. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.94.1.102

Feinberg, D. R., Jones, B. C., DeBruine, L. M., Moore, F. R., Smith, M. J. L., Cornwell, R. E., … & Perrett, D. I. (2005). The voice and face of woman: One ornament that signals quality?. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26(5), 398-408.

Germine, L., Russell, R., Bronstad, P. M., Blokland, G. A., Smoller, J. W., Kwok, H., … & Wilmer, J. B. (2015). Individual aesthetic preferences for faces are shaped mostly by environments, not genes. Current Biology, 25(20), 2684-2689.

Henriques, M., & Patnaik, D. (2021). Social Media and Its Effects on Beauty. IntechOpen. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.93322

Holzleitner, I. J., & Perrett, D. I. (2017). Women’s preferences for men’s facial masculinity: trade-off accounts revisited. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 3, 304-320.

Hönekopp, J. (2006). Once more: is beauty in the eye of the beholder? Relative contributions of private and shared taste to judgments of facial attractiveness. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 32(2), 199.

Hunt, K. A., Fate, J., & Dodds, B. (2011). Cultural And Social Influences On The Perception Of Beauty: A Case Analysis Of The Cosmetics Industry. Journal of Business Case Studies (JBCS), 7(1). https://doi.org/10.19030/jbcs.v7i1.1577

Kachel, S., Steffens, M. C., & Niedlich, C. (2016). Traditional masculinity and femininity: Validation of a new scale assessing gender roles. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 956. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00956

Kleisner, K., Tureček, P., Saribay, S. A., Pavlovič, O., Leongómez, J. D., Roberts, S. C., … & Varella, M. A. (2023). Distinctiveness and femininity, rather than symmetry and masculinity, affect facial attractiveness across the world. Evolution and Human Behavior.

Langlois, J. H., Kalakanis, L., Rubenstein, A. J., Larson, A., Hallam, M., & Smoot, M. (2000). Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological bulletin, 126(3), 39

Little, A. C., Burt, D. M., Penton-Voak, I. S., & Perrett, D. I. (2001). Self-perceived attractiveness influences human female preferences for sexual dimorphism and symmetry in male faces. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 268(1462), 39-44.

Mazur, A. (1986). U.S. Trends in Feminine Beauty and Overadaptation. The Journal of Sex Research, 22(3), 281–303. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3812567

Meltzer, A. L., & McNulty, J. K. (2015). Telling Women That Men Desire Women With Bodies Larger Than the Thin-Ideal Improves Women’s Body Satisfaction. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(4), 391-398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550614561126

Merran Toerien; Sue Wilkinson (2003). Gender and body hair: constructing the feminine woman. , 26(4), 333–344. doi:10.1016/s0277-5395(03)00078-5

Nault, Kelly A.; Pitesa, Marko; Thau, Stefan (2020). The Attractiveness Advantage At Work: A Cross-Disciplinary Integrative Review. Academy of Management Annals, 14(2), 1103–1139. doi:10.5465/annals.2018.0134

O’Connor, Jillian J. M.; Fraccaro, Paul J.; Pisanski, Katarzyna; Tigue, Cara C.; Feinberg, David R.; Stephen, Ian D. (2013). Men’s Preferences for Women’s Femininity in Dynamic Cross-Modal Stimuli. PLoS ONE, 8(7), e69531–. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069531

Penton-Voak, I. S., Little, A. C., Jones, B. C., Burt, D. M., Tiddeman, B. P., & Perrett, D. I. (2003). Female condition influences preferences for sexual dimorphism in faces of male humans (Homo sapiens). Journal of Comparative Psychology, 117(3), 264.

Pereira, K. J., da Silva, C. S. A., Havlíček, J., Kleisner, K., Varella, M. A. C., Pavlovič, O., & Valentova, J. V. (2019). Femininity-masculinity and attractiveness–Associations between self-ratings, third-party ratings and objective measures. Personality and Individual Differences, 147, 166-171.

Ramsey, J. L., Langlois, J. H., Hoss, R. A., Rubenstein, A. J., & Griffin, A. M. (2004). Origins of a stereotype: Categorization of facial attractivenes

Reilly, M. J., Tomsic, J. A., Fernandez, S. J., & Davison, S. P. (2015). Effect of facial rejuvenation surgery on perceived attractiveness, femininity, and personality. JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, 17(3), 202-207.

Rice, Karlie; Prichard, Ivanka; Tiggemann, Marika; Slater, Amy (2016). Exposure to Barbie: Effects on thin-ideal internalisation, body esteem, and body dissatisfaction among young girls. Body Image, 19(), 142–149. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.09.005

Roth, T. S., Samara, I., Perea-Garcia, J. O., & Kret, M. E. (2023). Individual attractiveness preferences differentially modulate immediate and voluntary attention. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 2147.

Rubenstein, A. J., Kalakanis, L., & Langlois, J. H. (1999). Infant preferences for attractive faces: a cognitive explanation. Developmental psychology, 35(3), 848.

Sari, M., Ayuningtyas, C. D., Cristin, S., & Rahyadi, I. (2022). BEAUTY OF WOMEN FROM IDEAL APPEARANCE AND UNDERSTANDING OF BEAUTY STANDARDS: A LITERATURE REVIEW. INFOKUM, 10(5), 686-699. https://doi.org/10.58471/infokum.v10i5.1124

Shu-Yueh Lee (2009). The Power of Beauty in Reality Plastic Surgery Shows: Romance, Career, and Happiness. , 2(4), 503–519. doi:10.1111/j.1753-9137.2009.01051.x

Van de Ven, Niels (2015). Envy and admiration: emotion and motivation following upward social comparison. Cognition and Emotion, (), 1–8. doi:10.1080/02699931.2015.1087972

Vukovic, J., Feinberg, D. R., Jones, B. C., DeBruine, L. M., Welling, L. L., Little, A. C., & Smith, F. G. (2008). Self-rated attractiveness predicts individual differences in women’s preferences for masculine men’s voices. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(6), 451-456.

Vukovic, J., Jones, B. C., DeBruine, L., Feinberg, D. R., Smith, F. G., Little, A. C., … & Main, J. (2010). Women’s own voice pitch predicts their preferences for masculinity in men’s voices. Behavioral Ecology, 21(4), 767-772.

Wolf, N. (2013). The beauty myth: How images of beauty are used against women. Random House.

7 comments

It would be interesting to test whether those steps that are perceived as attractiveness-enhancing actually *do* enhance attractiveness.

In terms of weight for instance, WHR and fat distribution in general matters. High-WHR (“apple-shaped”) women may be perceived and perceive themselves as “fat” even when they have a BMI in a normal range. In this case, weight loss won’t change much since you can’t naturally target fat distribution.

I don’t remember where I read that part of what causes anorexia is high-WHR women misperceiving themselves as fat because they lack curves.

This is one of those truths that is simultaneously manifestly unfair and also something that politics can do nothing about. Generally the progressive response to such thoughts is denial (see also their rejection of IQ as a real thing which has significant impact on an individual’s quality of life). This is irrational but it is understandable, since the progressive paradigm is that every social injustice can be solved with more politics (and to be fair 90% of injustices can be handled this way; traits like beauty and IQ are the exception to the rule).

> In some cases, traits that signal health and low mutational load are associated with beauty (e.g. facial symmetry or averageness). In others, traits that signal fertility are associated with beauty (the hip-to-waist ratio).

Curious what do you think about argument from: https://hotelconcierge.tumblr.com/post/140529495929/how-to-be-attractive

———-

> Arguments that seek to explain the nuances of human behavior via natural selection are almost always misguided. Dr. Saad’s argument is not the exception. I do not dismiss evolution; rather, I argue that evolution has had powerful effects way upstream of any one trait. Hardware keeps us alive, but our lives are run by software.

> Case study: Dr. Saad states that symmetrical faces are universally preferred over asymmetrical faces. This is almost true, but…

> In most cases, then, artificially-induced symmetry does not prettify a face. So why do we find symmetric faces attractive?

> Faces with “average” features tend to be extremely attractive, e.g. Jessica Alba, if you’re amnestic to the Fantastic Four remakes. (…) experiments have found that number of faces averaged positively correlates with attractiveness.

> Hence, don’t mess with the sliders on the character creation screen. We are not programmed to seek symmetry or clear skin, evolution just says that normal = good. How do we know what’s normal?

> > Fifteen minute-old neonates show no preference for attractive faces over unattractive faces. But 72 hours later they already stare longer at faces judged by adults to be attractive than they do at unattractive faces. This rapid development of an appreciation of facial beauty (as judged by adults) might be explained by the fact that an averaged face made of 32 faces looks almost indistinguishable from any other 32-face averaged face even when they are created from a completely different set of individuals. It is thus possible that an average of only 32 facial exemplars is sufficient to approximate the population mean, and thus produce a prototype that is shared by almost everyone in a community. (Wikipedia)

> This directly refutes one of Dr. Saad’s claims. See also: “Three-month old infants, but not newborns, prefer faces of the same race.” We form a model of the world and find comfort when the world conforms to our model: allegory of the cave, natch.

> Waist-hip ratio is also a bit messier than Dr. Saad implies. American men do prefer a low waist-hip ratio (around 0.68), at least when looking at 2-dimensional figures, although note that this is close to the mean WHR of young American women (0.72–0.73). In comparison, young Hazda men prefer a WHR of 0.78, close to the mean WHR of 0.79 among young Hazda women.

> Observation: no one cares about secondary sexual characteristics more than high schoolers. In college, waifish tumblrgirls and late-blooming tumblrboys do pretty well; in high school, they are ignored, hence Tumblr. Why are high schoolers so superficial? If you recall, when you first discovered the thrill of senpai noticing you, it was the most exciting thing ever. So you stopped paying attention in class and started scanning for qts. Who was willing to flirt back?

> Puberty prompts you to seek out a mate. Puberty’s dark magic also lowers the WHR of women, increases the shoulder-hip-ratio of men, increases bust size (♀), musculature (♂), penis size (♂), cheekbones (♀), and jawline (♂), all stereotypically attractive traits. Even for a congenitally blind man with an allergy to pop culture, a first makeout session will involve lots of breast caressing, booty squeezing, and running of hands from narrow waist onto broad hips.

> The map is thus written: wide hips = good chemicals, “even better than videogames!” Puberty onsets earlier in girls than boys, so a girl’s first boyfriend is likely to be taller, older, and more competent than the boys her age = same principle. Culture acts as a positive feedback loop for these preferences, but it is not necessary for them to emerge.

> With luck, this explanation will annoy people on both sides of the nature/nurture debate. Evolution tells us to form prototypes, but it says nothing about how those prototypes should appear.

Also this footnote:

> [2b]. Indeed, most arguments of evolutionary psychology disintegrate if you look at them for more than five seconds and are not currently high on nitrous. Evolution acts primarily on DNA. There are only 20,000 genes in the human exome. Do you really think a subset of them encodes a preference for big butts and the inability to lie? For 0.7 over 0.6 or 0.8, starting at puberty but not before? What do those proteins look like?

> Don’t get me wrong, wide hips (or, upstream, high estrogen) may increase fertility and thus be selectively advantageous, but this has nothing to do with the male gaze. If you don’t get this, please take a break from this essay and come back when you’ve finished Hooked on Phonics.

The two most important things when it comes to female physical attractiveness are the face and BMI. Those two things probably account for like 95% of female attractiveness.

When it comes to faces the cute faces of pubescent girls about 12-14 are rated most attractive. It’s often claimed in the literature that men find “neotenous” faces most attractive but this is a slightly wrong interpretation. Most studies on female attractiveness only use 18+ models. The women rated most attractive in these studies are those that happen to have retained the facial proportions they had as pubescent girls. This is then interpreted to mean that men prefer adult faces with “neotenous proportions” that make them look like pubescent girls. Well, who else looks like pubescent girls? Actual pubescent girls, obviously. It’s not neoteny but immaturity that men find attractive. What men find the most attractive is simply the cute faces of pubescent girls, not adult faces.

In South Korea facial reshaping surgery is very popular. So what facial proportions do women choose to have? They choose to make themselves look like pubescent girls, because they instinctively know men find that the most attractive. Here’s some examples:

https://i.imgur.com/eYvxlVa.jpeg

https://i.imgur.com/8F5Eqax.jpeg

https://i.imgur.com/qgu9rqA.jpeg

For comparison this is a real pubescent Asian girl about 12 (Nozomi Kurahashi). She looks basically the same as the after pics:

https://i.imgur.com/EWUTYc3.jpeg

Notice also that the skin in the after pics has been made to look softer and smoother like the skin of a pubescent girl.

The BMI rated most attractive is about 18-20 which is low for an adult woman but normal for a young teen or pubescent girl. BMI also increases after pregnancy. It would have been important for men in ancestral times to prefer females who are young and haven’t started reproducing yet as these females would be capable of giving them the most offspring over the long-term. A low BMI is another sign of immaturity and nulliparity that men have evolved to find attractive.

So if a woman wants to make herself more attractive to men the two best things to do is make her face look young and cute, and lose weight if she needs to. In other words, make herself look like a young slim schoolgirl.

—

A lot of fuss has been made over the importance of WHR (waist to hip ratio) but it’s just not that important in the real world. As long as a woman has the general hour glass figure it’s ok. It doesn’t matter if the precise ratio is 0.7 or 0.8.

Boob size is probably over-rated too. Breast pertness is more important than size. Look at some footage of naked people in a traditional foraging society and you’ll see what I mean. I recommend watching “Tears Of The Amazon”. The adult women who have had babies have horrible saggy boobs while the nulliparous young teen and pubescent girls have nice perky boobs with nice soft unused nipples. Their pert boobs are an honest signal saying “Look! I’m young and haven’t had a baby yet! I still have all my reproductive years ahead if me and will be capable of giving you many babies over the long-term! Pick me as a wife!” When women have boob implants they make them both big and pert giving them a kind of super-pubescent look.

The vulvas men find most attractive are also those of pubescent girls. Many women have had their labia trimmed down to make themselves look like a pubescent girl down there because they know men find it more attractive just like men prefer the faces of pubescent girls, but maybe this is too taboo to talk about here and I’m going to stop now.

LOL I didn’t expect my comment to be approved. It’s not that there’s some kind of coordinated conspiracy to “suppress the truth” that men find minors most attractive but it happens through self-censorship and individual bias. Maybe in a few generations when pedo-hysteria has died down a bit we can start being a bit more rational and objective about the issue.

Here’s a bonus video:

https://i.imgur.com/9sJOy1w.mp4

Fantastic article! As a PhD student, I wonder why you are posting a very well researched and referenced article which can easily be turned into a legit publishable quality paper? You even enabled autocompletion in the comment section, I have never seen a website with such a feature before, you put so much effort into everything!